There’s something undeniably seductive about Andreas Mühe’s spare, yet sumptuous photographs. A superb technician and gifted storyteller, Mühe uses both formal and narrative elements with concentrated, yet restrained intensity to create images of arresting beauty and drama that will haunt you long after you look away.

Mühe’s Mischpoche (from the Yiddish “mishpokhe”, meaning tribe or clan) on view at the Hamburger Bahnhof Museum of Contemporary Art in Berlin centers on family. It’s an unusually comprehensive effort as Mühe has included the dead as well as the living in his group family portraits. Working from old photographs of the deceased, Mühe creates remarkably lifelike, three-dimensional versions of them in silicone. He arranges the dolls (as he calls them) together with the living family members into a kind of tableau vivant that he then photographs. The large-format camera serves Mühe well in the ruse of passing his dolls off as living people: since it makes everything look artificial, it visually evens out the playing field between the inanimate and animate figures.

Andreas Mühe, Woman III XIV

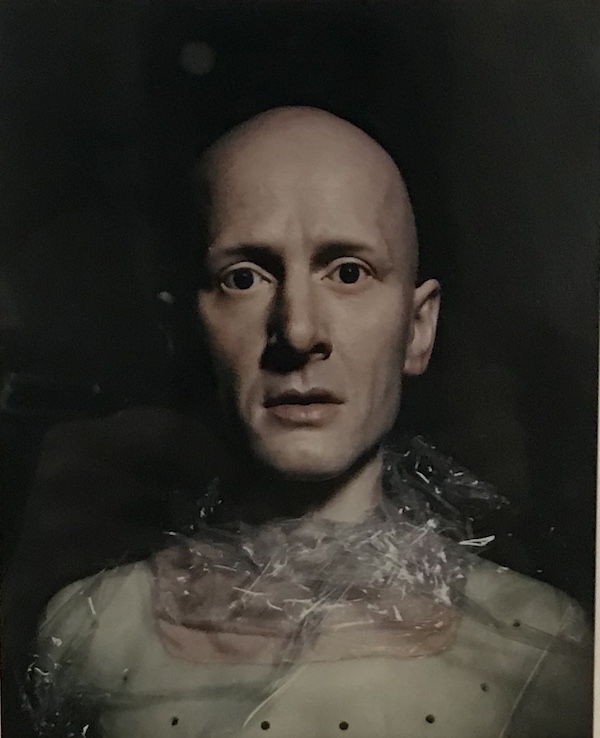

To highlight his process, Mühe takes pictures of the silicone dolls at various stages of production. The human likenesses are so realistic, it’s disorienting and disturbing and it takes us a minute to digest and comprehend what is going on. These individual portraits—I particularly liked Vater XIV and Woman III XIV—can be viewed as a means to an end, but they are in and of themselves powerful, stand-alone images—confusing, creepy, interesting and deeply affecting.

The apotheosis of the exhibition are the two large color portraits of the Mühe family exhibited dramatically in a darkened room. In Mühe I, the family is arranged around pater familias Ulrich Mühe. Mühe has taken an inclusive approach to the portrait with Ulrich’s second and third wives (both deceased) posed congenially together. Two children (Mühe’s half-brothers) are represented by lambs held on leashes by their mother, the late actress, Susanne Lothar. They are the only two family members not represented in human form. Mühe chooses to recreate the dead as they were at age 40, while the living, of course, are their normal chronological age.

Andreas Mühe, Vater XIV

The theater looms large over the group portraits which appear to have been taken on a stage in mid-scene of a performance. Indeed, the portraits recall production stills like the ones put up in a theater lobby during the run of a play. The theater conceit is a reference to the family members’ occupations, but it also underscores the artificiality of the whole thing. To emphasize this even more, Mühe intentionally includes camera equipment and camera tracks in the foreground of the photographs and he even appears in shadow on the right side of the Mühe II, a Christmas scene complete with decorations and lavish tree.

Andreas Mühe, Mühe I

These fictionalized family portraits are really quite moving. In creating them, Mühe brings back to life dead family members and mends their fractured relationships. It’s what we would all love to do. I can’t help but think how working all those hours to recreate his father, Mühe’s thoughts, both conscious and unconscious, would have been completely absorbed by him, their relationship, etc. Certainly, it’s a pale version of having the real person back, but what a gift that communion would have been.

There’s something macabre at recreating facsimiles of the dead and photographing them. But in doing so, Mühe provokes so many interesting thoughts about familial relationships, the ephemerality of experience, the nature of photography and, of course, truth vs. illusion, which in this era of fake news and deepfakes takes on special significance.

Andreas Mühe, Mühe II

Despite all the labor involved in producing the dolls (the project took four years) and emotional investment—imagine producing an exact replica of your dead father—they are merely a means to an end. Having served their purpose in the illusion of the family portraits, they will be destroyed after the exhibition closes.

Mühe primarily uses a large format camera which produces extremely high- resolution prints in which the smallest details are visible. This hyper-reality is not how the eye sees, and it imparts a curious artificiality to the photographs.

Andreas Mühe, Grimma I

Truth and illusion are recurring themes in Mühe’s work. His background, with parents deeply engaged with the worlds of theatre and film, most likely accounts for his interest in these dual forms of reality. Mühe’s mother is theater director Annegret Hahn. His late father was actor Ulrich Mühe. (Ulrich played the role of Stasi officer Gerd Wiesler in the searing 2006 Oscar-winning The Lives of Others.)

There is a quiet grandeur to Mühe’s work. Take for instance Grimma I, which references the town where Ulrich Mühe was born. Here, we see the ravages of one of Grimma’s periodic floods on a particular household. The dining room with its poignant, petit-bourgeois accouterments is a mess. The large plant, similar to the one in Mühe I, suggests this is a Mühe Family house. Mühe captures this image of private tragedy quietly and yet, with such elegance, transforming what could be such a depressing scene of banality into something of real beauty and deep emotional resonance.