Having been a curator of photography in a museum myself, I know that when a new department head is appointed at an institution with a long-standing collection, he or she has to make a statement with an exhibition exploring that collection in a way no one has before. That challenge has been met adroitly by Jim Ganz, who assumed the position of Senior Curator of Photographs at the Getty Museum in 2018. Drawing from the museum’s holdings of over 148,000 prints, the exhibition “Unseen: 35 Years of Collecting Photographs” is a survey comprising 200 “never-before-seen” prints. Ganz enlists contributions from all six of the photography curators already on staff at the museum. Between the premise for the exhibition and the number of hands contributing to it, the one danger was that the installation might seem incoherent rather than inclusive. That was avoided, but it takes some patient, thoughtful looking to appreciate its successes.

Veronika Kellndorfer, Succulent Screen, 2007

The exhibition has some conventional groupings by a single photographer—three framed and matted prints by Chicago documentarian of African-American life Dawoud Bey, for example, next to three nude self-portraits by the late SoCal photographer Laura Aguilar. But along with such traditional work, the show includes images very different in scale and intention. A counterpoint to Bey’s prints is found in Valérie Belin’s untitled billboard-size portrait from 2001 of a black woman. The image is given a freestanding wall in the diagonal pathway connecting the side galleries. Prints similar in scale that digital technology has made possible dominate some side galleries, too. A typically dark Gregory Crewdson that looks like a scene from a noir-ish movie, and approaches a movie screen in size, is placed next to a Candida Höfer of an 18th-century library in Weimar, Germany, that also aspires to being the size of the historic interior it records

A danger inherent in an exhibition as large as this is that recent large-scale prints will steal the show. A limited strategy the curators uses to avoid this is to bring together groupings of the same subject as seen by different photographers. Two walls hung with portraits of dogs in varying sizes meet at a corner. On other walls a variety of nude studies or imprisoned criminals are seen. The intended pièce de résistance of this curatorial strategy is found at the end of the exhibition, where the entire back wall is a symmetrical arrangement of 16 photographs of hands. This does illustrate the kind of depth the collection can have. The problem is that so many repetitions of a single subject, seen altogether, undercut the impact of any one image.

Martin Munkácsi, Big Dummies, 1927–1933

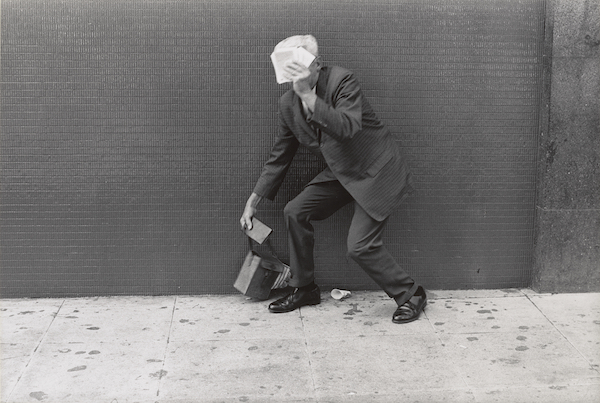

If large prints and groupings get all the attention, the more imaginative aspect of the curators’ work is missed. The installation is at its best when a few adjacent images are dialectical in relationship rather than identical in subject. Consider the fashion photograph Antonia and Mirrors (1963) by William Klein that has been hung next to Big Dummies (1927/33), Martin Munkácsi’s study of a crowd of men. As usual, I puzzled over the prints before looking at the labels. Photographs often talk to each other more informatively than the text on a label talks to the viewer. If you linger quietly, you can eavesdrop on the conversations that images are having with each other. The many fashion models in Klein’s print are the same model seen from different angles, and Munkácsi’s group of men are the heads of wooden dummies in a box. As an audience for Klein’s self-involved woman, Munkácsi’s gaggle of gawkers are put to shame. Such curatorial coups sometimes arrest our attention and go straight to our subconscious.

The dialogue between photographs fostered by a pre-war example like Munkácsi’s has the same verve and sophistication found in the best black-and-white movies of the 1930s. But curatorial coups aren’t limited to such intimate relationships. Noticeable in this regard is the response that a woman in another photograph seems to be having to the enormous Valérie Belin portrait. Though it stands alone, Belin’s piece isn’t isolated. There are photographs of other women on two of the three walls Belin’s subject looks out on. A large-scale photograph by Tina Barney is hung directly opposite Belin’s, though at least 25 feet away. In Barney’s image, a woman has turned away from a huge TV screen with a dazed expression on her face. Though she stares in the direction of Belin’s subject, does she see her? She seems to be stunned by the unsettling directness with which Belin’s subject looks at her. Issues ranging from feminism to racism seem to be evoked by juxtapositions in this part of the installation.

Anthony Hernandez, Los Angeles #1, 1969

Elsewhere, unlikely pairings of photographers offer—because of their dissimilarity—an opportunity to see each one’s work anew. New York bad boy Robert Mapplethorpe and New Orleans aesthete Clarence John Laughlin are side by side because each found an arresting subject in a circular staircase seen from an obtuse angle. Another group of similar compositions consists of swirling abstractions on glass that are the work of three Japanese photographers living in the U.S. between 1929 and the early 1940s. This material is special because it came into Getty holdings recently with the private LA collection assembled over many years by Dennis Reed.

I’ve known Reed for 15 years and have particularly admired him because he was building a unique collection on a very limited budget. He has specialized in Japanese-Americans who were amateur photographers belonging to camera clubs—some of them sent to internment camps during World War II. The Getty has had the perspicacity to acquire Reed’s collection partly as a tribute to its unique quality and partly in recognition that it fills a gap in the Getty’s own collection. A text in the exhibition honors Reed for his unique contribution to the history of photography as well as his enhancement of the Getty’s holdings.

Myoung Ho Lee, Tree #2, 2006

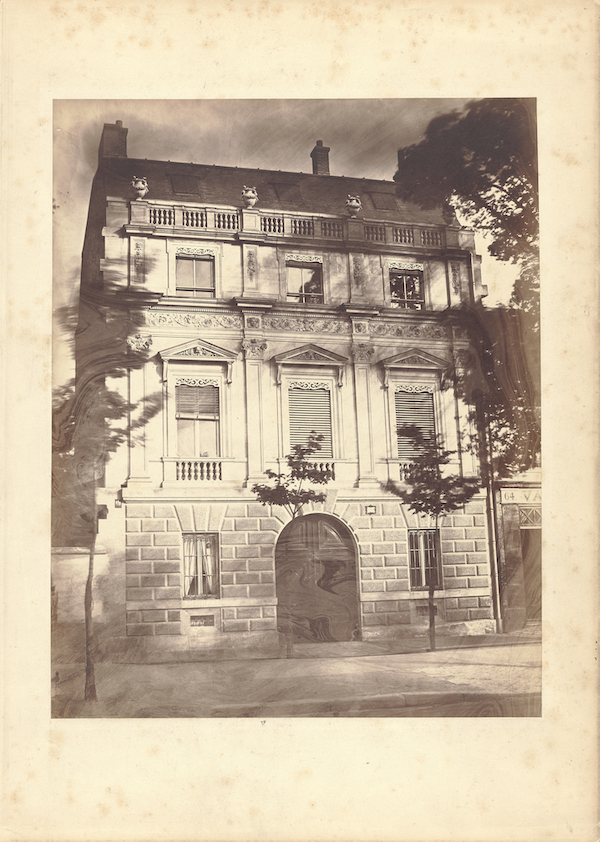

The last gallery in the exhibition is devoted to recent acquisitions. The Dawoud Bey and Laura Aguilar prints are hung here, as are the three glass abstractions from Reed’s collection. On the gallery’s opposite end are two pieces so different in scale, medium and date that they seem an A to Z attempt to sum up the exhibition. They definitely exemplify the range of James Ganz’ interest in photography. A small salted-paper print on the short wall beside the gallery entrance is a study of a house in Paris, ca. 1857, made by Bisson Frères. The elder of these two brothers had been an architect, and their mission as photographers was to document historic buildings in Paris. The house seen here is an arresting example made more so by the way that trees and their windblown shadows fall on the façade.

The photograph’s power is reflected in the obsession Ganz had with it. “This is a photograph that I first saw in 2004 at Hans Kraus [Gallery], New York,” Ganz told me. “I fell in love with it. I was at the Clark Art Institute then. and I wanted to get it for the collection. But I didn’t have the funds available. So it didn’t happen. When I came to the Getty, one of the first phone calls I made was to Hans Kraus, and I asked, ‘Do you still have that one of the house?’ Kraus said, ‘Oh, yes, I still have it.’ So, 15 years later I got it for the Getty.” Such persistence of vision, and memory, might seem excessive. But it’s a capacity that can serve a curator well.

Bisson Frères, House at 66 Avenue Montaigne, Paris, about 1857

Though also an image of an architecturally significant house, the photograph with which Ganz has paired the Bisson Frères document couldn’t be more different. It’s a 2007 silkscreen print on thick, green glass made by Veronika Kellndorfer and titled Succulent Screen. The composition looks out from a 1923 Frank Lloyd Wright house in the Hollywood Hills. The subject is the plantings outside seen through floor-to-ceiling windows. Kellndorfer’s multi-panel print that leans against the gallery wall looks as if it must be actual size. Oddly, situated that way, Kellndorfer’s contemporary image connects to the Bisson Frères’ vintage print because the latter’s subject also seems to lean away from us—a result, no doubt, of the quirkiness of 19th-century lenses. More contrarily, where Kellndorfer’s view is out from inside the house, the house that the Bisson Frères documented has windows mostly shuttered or with closed curtains.

As with the Bisson Frères’ little print, the acquisition of Kellndorfer’s monumental one entailed a bit of a saga. The print had been offered to the Getty as a gift by LA dealer Christopher Grimes when he closed his gallery. Ganz presented the Kellndorfer for acquisition because he is as eager to anticipate the future of photography as he has been to honor its past. But there was some push-back from the administration because such a large, fragile piece might require very complicated (read, expensive) storage. Undaunted, Ganz managed to get the acquisition approved anyway, precisely because keeping pace with the future of the medium is as important as continuing to honor its past.

0 Comments