“Revolution in the Making: Abstract Sculptures by Women, 1947–2016” inaugurates the sprawling new complex recently opened by Hauser Wirth & Schimmel in downtown Los Angeles’ Arts District. Housed in a former flour mill that dates back to the late 19th century, the gallery occupies an entire city block, including a bookstore and an upscale restaurant, with more square feet of gallery space than many museums. It seems roughly equivalent to the Geffen Contemporary at MOCA which sits only a few blocks away. The debut exhibition presents an ambitious survey of abstract sculpture from the last 70 years made exclusively by women. It’s an unusual perspective and an interesting one, bridging late modernist artists like Louise Bourgeois to Process Art icons Eva Hesse and Lynda Benglis to younger sculptors Liz Larner and Jessica Stockholder. Containing nearly 100 works by 34 artists, the show continues the trend of museum-quality exhibitions that have been mounted in recent years by mega galleries such as Gagosian and Pace in New York. It is a peculiarity of our times that private galleries have the resources and clout to produce exhibitions that rival (or surpass) those at venues such as MoMA or LACMA.

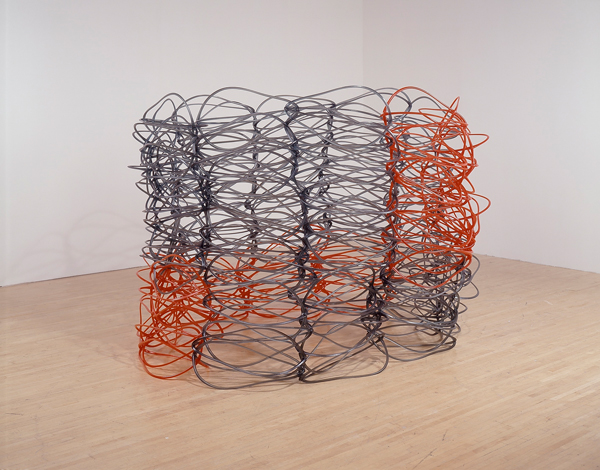

Liz Larner, Reticule, 1999 – 2000, Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, ©Liz Larner, Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles

Limiting the show to only women sculptors creates an alternative context that brings up a number of thought-provoking issues: Is there an inherent difference between sculpture made by men and women? Is it legitimate to select artists based upon their gender? How would the show have been different if it had simply been abstract sculpture from the last 70 years, including both sexes? As it turns out, the all-women concept has generated a mesmerizing exhibition where the varied formal vocabularies play off each other quite well, and the myriad of works retain a kind of visual unity because of a consistency of organic form throughout. With the inclusion of male abstract sculptors from the same period such as David Smith, Donald Judd and Richard Serra, the show certainly would have had a different formal character, more angular and rectilinear, more hard and metallic.

Eva Hesse, Aught, 1968, Collection of University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, ©The Estate of Eva Hesse, Photo: Benjamin Blackwell

At center stage are the several artists who were part of the Postminimal or Process Art movement whose particular achievement was to translate the idioms of Abstract Expressionist painting into a sculptural form. Two iconic 1968 works by Eva Hesse, Aught and Augment, which are well known through photographs of the “9 at Leo Castelli” show, an early Postminimal exhibition, are brought together again in their original arrangement, Aught hanging loosely off the wall and Augment below on the floor. Both works are composed of latex and canvas and utilize repetition of vaguely rectangular elements that rely upon the room’s architecture to support their pliable structures. Latex, a rubbery material used for molds, was adapted by Hesse for its inert and artless quality; unfortunately, it is not an archival material, and nearly 50 years later Aught appears to be on the verge of crumbling into dust, which most likely would have pleased Hesse, who loved the expression of fragility in her work.

Lynda Benglis, Wing, 1970, © Lynda Benglis / Licensed by VAGA, New York NY, Courtesy Hauser & Wirth and Cheim & Read, New York

Lynda Benglis, Hesse’s Postminimal cohort, is represented by two works cast in aluminum from originals made from expandable polyurethane foam. A staple of sculpture process today, urethane foam was new when Benglis began to use it, and she exploited its natural tendency to erupt into lava-like organic forms whose extemporaneous nature created a foil to the tradition of carefully carved organic forms that had dominated sculpture up to this point. Wing (1970), originally formed by pouring urethane onto a shelf mounted on the wall, is the formally more interesting work, as the material began to cascade down from the wall and shelf before setting, creating a more varied and dynamic form than the poured floor piece, Eat Meat (1969–75). Like Hesse, Benglis’ relation to abstract painting was paramount; the 1967 Pollock retrospective at MoMA was a watershed for that generation of artists who extrapolated the possibilities in process-oriented sculpture from the drip technique. Those artists, in turn, created their own watershed, as many of the tendencies inherent in process sculpture have prevailed since then and are visible in the exhibition.

Eva Hesse, Augment, 1968, Installation variable, ©The Estate of Eva Hesse, Photo: Genevieve Hanson

Of the recent works, Shinique Smith’s monumental Forgiving Strands (2015-16) is one the few sculptures that manages to own the space it inhabits. Snaking down the length of a long narrow gallery, the work consists of linear organic forms that gesture like strokes of paint. Composed mainly of stuffed fabric and clothing that hang from the ceiling, the piece owes a tremendous debt to Eva Hesse’s hanging fiberglass-and-latex rope sculptures that were done at the very end of her short career. Jessica Stockholder’s wacky small-scaled constructions mix found objects with abstract forms and painted surfaces in a similar way to her installations. The blending of both painted and sculpted vocabularies creates interest in her works, as it does in the wall sculptures by Sonia Gomes, which twist around in a kind of three-dimensional drawing akin to some of the early Constructivist open-form sculptures.

![Ruth Asawa, Untitled, [S.143, Hanging Five-Lobed, Multi-Layered Continuous Form within a Form] 1996© Estate of Ruth Asawa courtesy Christie’s Photo: Laurence Cuneo © 2015](https://artillerymag.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/HWS_ASAWA71561.jpg)

Ruth Asawa, Untitled, [S.143, Hanging Five-Lobed, Multi-Layered Continuous Form within a Form] 1996 © Estate of Ruth Asawa, courtesy Christie’s, Photo: Laurence Cuneo © 2015

There are many other delights in the show, such as the open gestural sculptures of Claire Falkenstein, the brooding wall reliefs of Lee Bontecou, the knitted wire columns of Ruth Asawa, the modular wire works by Gego, and Liz Larner’s cast polyurethane cage-like construction, to name just a few. The exhibition makes two things very clear: the abiding influence of Postminimal sculpture from the late 1960s on today’s abstract sculpture, and the way that influence has helped to create a lively, somewhat kooky kind of contemporary nonfigurative 3D art that stands in contrast to the male dominated geometric tradition. Sculpture has frequently struggled to achieve the looseness and spontaneity of drawing and painting, and much of the work in this exhibition is testament to the possibilities of these qualities in abstract sculpture which today still holds great untapped potential for artists.