“The Democracy Project: 2020” manifests the great, besieged “project of Democracy” as an online exhibition for Artillery’s September/October issue, featuring recent work by a diverse selection of the West Coast’s most compelling artists. Whether approaching the theme ironically, or with reverence (or a bit of both), the artists below are chosen for their political engagement, provocative content, and significant contributions to the diversity of the art world.

ARTISTS: Kim Abeles, Sama Alshaibi, Aaron Coleman, Eileen Cowin, Asad Faulwell, Corey Grayhorse, Mark Steven Greenfield, Salim Green, Ken Gonzales-Day, Alexander Kritselis, Ann Le, Alejandro Macias, Renée Petropoulos, Mike Reesé, Miles Regis, Julio M. Romero, Stephanie Syjuco, Meital Yaniv. —Lawrence Gipe

FORWARD by Antoine Girard

Though the word democracy in this moment connotes for many a political party or side, the term also reflects a process. Democracy is a practice, a set of decisions that vacillates permanently between our light and darkness.

The state of the pandemic left me and many artists included in “Democracy 2020” at a new point of reflection. Months of time reluctantly passing in our homes, we were left living together separately to ask new questions. What side of history are we really on? What happens when protest becomes the only space to commune?

The artists convened here all illuminate the human connections at the heart of democracy even as they remind us of the power of place. Over the past months, Angelenos have seen the ideas we’ve lived our lives by at once in flames and on the cusp of rebuilding. “The Democracy Project 2020” expresses where we have been and the creative impulses we have held on to. This exhibit expresses where we have been and the creative impulses we have held to. I invite you to especially reflect on the location of the artist as you consider voices from Southern California (and beyond) responding to a world made—and remade—through collective process.

Mike Reesé

Mike Reesé, 2020, LOST TAPES (EXTENDED VERSION), 84 in. x 96 in., acrylic on unstretched canvas, brass, polyester jerseys

As well as being an artist, Mike Reesé is part of DREAMHAUS, a Los Angeles-based 501c(3) art nonprofit organization that he founded with Nikkolos Mohammed in 2014. Working alongside schools in South Central LA to provide lectures, workshops, and supplies, the organization is dedicated to implementing arts as an educational tool and a vehicle toward universal innovation for people and children around the world.

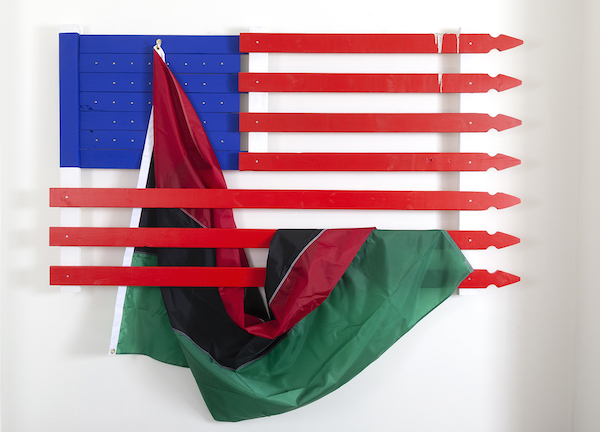

Aaron Coleman

Aaron Coleman, 2019, The Pietà, lumber, latex, acrylic, enamel, blueberries, pepper, cigarette ash, Pan-African flag and hardware

The 36-star flag, known as the “Lincoln Flag,” cradled Lincoln’s head after he was shot and represented the United States during the ratification of the 13th amendment. This assemblage examines the failures of that amendment as it was followed by more than 100 years of Jim Crow. The stripes of the flag, presented here as red fence pickets, re-contextualize a symbol of the American Dream revealing a history of red lining, and many other racist laws and policies. Bird shit adorns the pickets offering a literal and symbolic impugnation of the freedoms this flag claims to represent.

Michelangelo’s The Pietà is chiseled in Carrara marble, quarried in Tuscany by prisoners forced into labor under brutal conditions. Taking its name from Michelangelo’s sculpture, my rendition presents the Pan-African flag hanging from a golden coat hook, its drapery resembling the pose of Christ held by Mary after the Crucifixion. This assemblage continues its historical exposition as it confronts the history of free labor as well as the role of the church in its perpetuation of and benefit from racist ideas and policies during the reconstruction era.

Stephanie Syjuco

Stephanie Syjuco, 2020, Chromakey Aftermath 2, archival pigment print framed, 36″ x 24″

“Chromakey Aftermath” is part of a series of photographs that explore how media representation of public protests can distort and manipulate meaning. Chaotic compositions of protest props — fabricated entirely in bright green chroma key color — are photographed against a “neutral grey” backdrop. Chroma key is a visual effects technique used to composite images or videos, allowing an editor to superimpose new backgrounds or settings for the original image. This work restages objects that can be faked or re-presented for truth, transforming the meaning of the props and the intent of the protestors.

After witnessing multiple protests in early 2017 between white supremacist alt-right groups and anti-fascists in the San Francisco Bay Area, I was struck by the detritus and objects left at the scenes, as well as items confiscated by police that were interpreted as potential weapons. Many media reports were fixated on comparing each political side in equal terms, essentially rendering fascist viewpoints as legitimate ones, and painting anti-fascist movements as dangerous. These protest “aftermath” images are seen as starkly malleable and rendered disturbingly blank, akin to a scene open to interpretation. The green fabric represents information that can be faked or re-presented for truth, transforming the meaning of the props and the intent of the protestors. Over three years later, and at the cusp of the 2020 Presidential election, the concerns of this work, including the right to protest, have been further amplified by the public outcry and protest in support of Black Lives Matter, and the rise in white supremacist retaliation at the highest levels of government.

Ann Le

Ann Le, 2020, Terrorscape 2 Banyan, digital print

Tear x Scape / Terrorscape touches on weapons of warfare used on the landscape globally.

Tear gas was first used in World War I in chemical warfare. In 1925, the Geneva Convention categorized tear gas as a chemical warfare agent and banned its use during wartime. But its use by police in the U.S. is still legal.

Today, tear gas is the most commonly used form of what’s known in law-enforcement jargon as “less-lethal” force. Journalists file news stories of tear-gas deployment so regularly that pictures of smoke-filled streets have come to feel like stock photography—a theatrical backdrop of protest.

Julio M. Romero

Julio M. Romero, 2017, Borderlands XI, ink jet on paper

BORDERLANDS stems from documenting a process of personal reconstruction happening within the current geopolitical context of tension and rupture in the border strip of northwestern Mexico, mainly in the city of Tijuana, to which I return at the moment when it’s overcoming the aftermath of the “war versus narco”.

I return to my place of origin, which is now unknown to me, sometimes with the feeling that I’ve arrived here dragged by the wind, to a strange planet surrounded by situations, forms and characters now alien to me, forced to reconnect with everything that was once familiar. In parallel, the environment and I transform constantly, recognizing ourselves, while we get used to seeing each other and to being seen differently.

Julio M. Romero, Tijuana, 2019

Eileen Cowin

Eileen Cowin, 2020, It can(’t) happen here or The Wooden Cardinal of Hope, digital print

Democracy — I have heard this word in classes from elementary school through college, from all the talking heads on television, as well as in every newspaper and of course on social media, and I still had to looked it up. I went through many articles searching for the perfect way to “picture” this word while expressing my rage, my frustration, my anxiety and… my hope. In Wikipedia’s entry on democratic countries, I saw that the United States was number 25 and was listed as a “flawed democracy”. (I knew that all along but liked having it corroborated.) Recently so many people have defined the word for us: John Lewis (sigh), Jamelle Bouie, Barack Obama; there have been special editions of magazines like the New Yorker on The Future of Democracy. In my helplessness, I keep reading.

As with any word repeated over and over, the word democracy will disintegrate.

Eileen Cowin, 2020

Alejandro Macias

Alejandro Macias, 2020, A River Runs Through Her, oil, acrylic, graphite on cut panel, 20” x 16”

My work has been driven by his Mexican-American identity and the current social-political climate. Raised in the Rio Grande Valley (RGV), my body of work addresses themes of heritage, immigration and ethnicity, which are set in contrast to a critical engagement with the assimilation and acculturation process often referred to as “Americanization.”

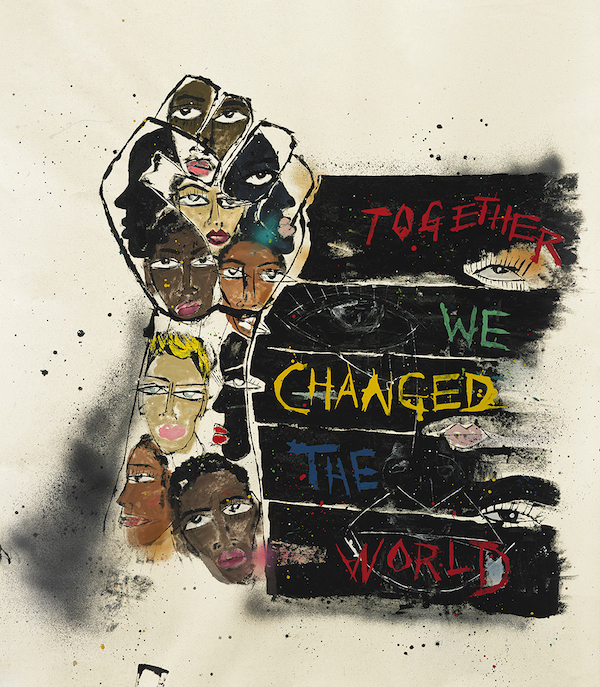

Miles Regis

Miles Regis, 2020, Together We Changed The WORLD!, mixed media

I refuse to accept the view that mankind is so tragically bound to the starless midnight of racism and war that the bright daybreak of peace and brotherhood can never become a reality… I believe that unarmed truth and unconditional love will have the final word.

– Martin Luther King Jr.

In the life and studio of LA-based, Trinidad-born artist Miles Regis, every action is an opportunity for creative self-expression. Prolific in both fine art and fashion design, Regis freely swaps the materials and languages of each to enrich the other. His large-scale mixed media paintings on canvas and linen incorporate dimensional collage elements of denim, buttons, leather, printed matter, sequins, and patches of eclectically sourced found textiles along with his dextrous, gestural, richly hued abstract and figurative painting techniques. Aggressively hopeful and humanistic, Regis embraces a storytelling stance in his stylized renditions of fundamental scenes of love, loss, freedom, survival, activism, and living history.

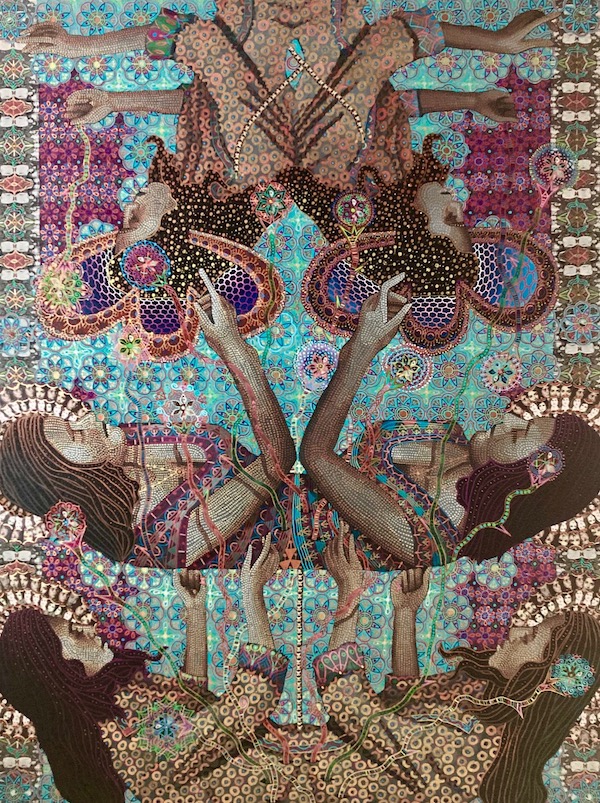

Asad Faulwell

Asad Faulwell, 2020, Les Femmes d’Alger, mixed media on canvas

“The women in the paintings killed people, “ Faulwell says of Les Femmes d’Alger”. “They killed civilians in the name of freeing themselves from colonialism. They then went through hell themselves. They were tortured by the French soldiers. They were ostracized by their own countrymen. They are victims, aggressors, killers. My interest was in the moral ambiguity of the whole thing.”

Corey Grayhorse

Corey Grayhorse, 2020, Roberta and Mike, photograph

Color and wonderment is a consistent thread throughout my work. A wide-ranging influence of styles in art, photography, and fashion combined with traditional, and pop culture influence my perspective. Through the lens, I create strange beauty and satire, eliciting emotional and social responses. Frozen in time through photography, the work becomes a window into a fantastic dream world, with hints of my reality, to draw an audience into my world.

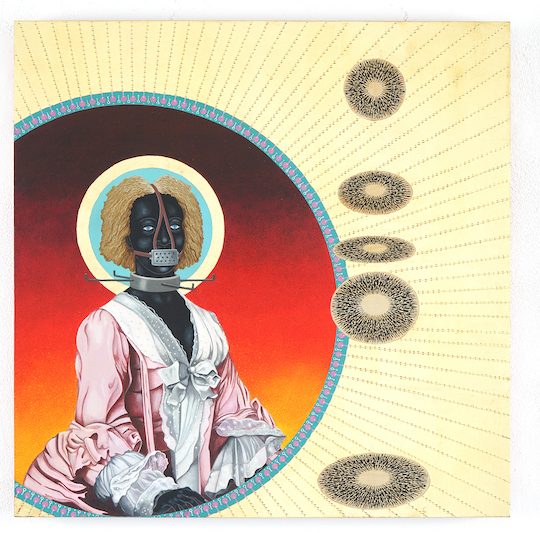

Mark Steven Greenfield

Mark Steven Greenfield, 2020 Escrava Anastacia, gold leaf and acrylic on wood panel, 24”x24”

A great deal of mystery surrounds Anastacia’s origins with some claiming her birthplace as Africa of royal lineage, while others suggesting she was born in Brazil. All accounts agree that she was a slave of exceptional beauty with arresting blue eyes. She was purported to have possessed remarkable healing abilities and a number of miracles are attributed to her. She was very cruelly treated by her masters and was made to wear a muzzle-like facemask and heavy iron collar. The reasons for this punishment vary from trying to incite other slaves escape, to the claim that she resisted rape by her master, to a mistress jealous of her beauty. After a prolonged period of suffering she died of tetanus brought on by the slave collar. It’s claimed that she healed the son of the master and mistress and forgave them as she died. There have been repeated attempts to have her canonized as a saint, but the Catholic church refuses to acknowledge her existence, and has had her image removed from all church properties in Brazil. Nonetheless Anastacia has many devoted followers among the poor and disenfranchised and shrines to her can be found throughout the country.

Kim Abeles

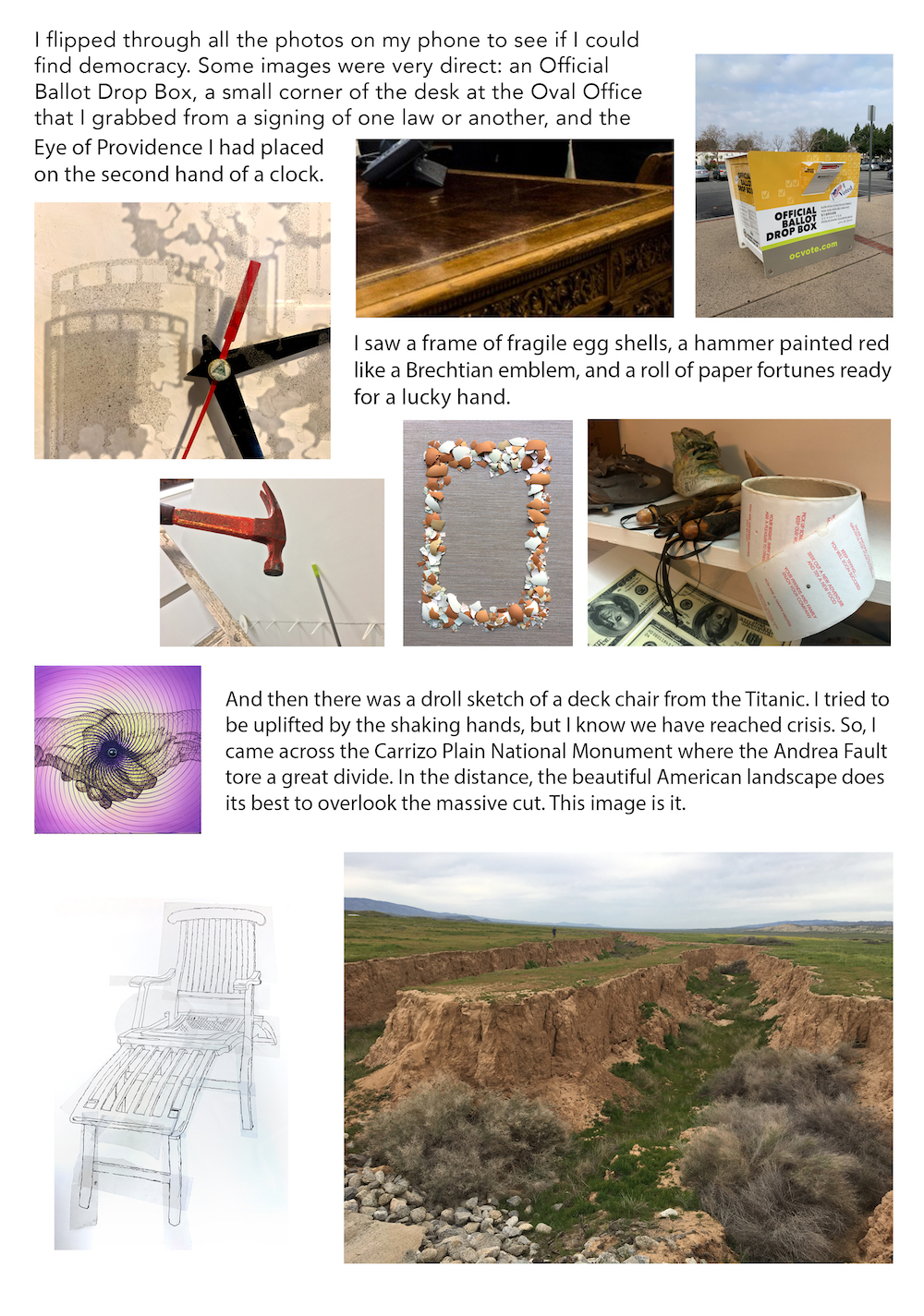

Kim Abeles, 2020, Looking for Democracy, text, and image

Renée Petropoulos

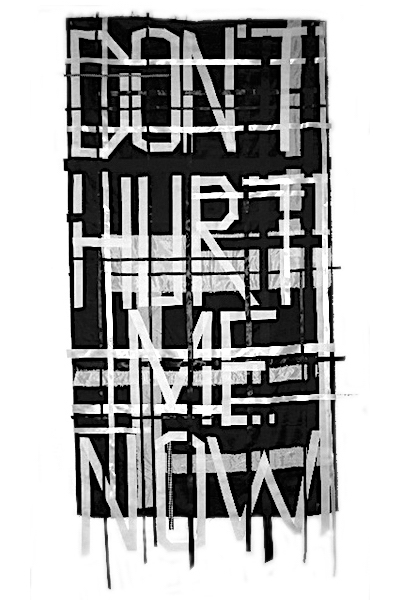

Renée Petropoulos, 2011, Don’t Hurt Me Now, ribbon, fabric, notions, 64” x 40″

This series of works began several years ago and is on-going. The works began as a way to transfer a type of refrain – a way to re-think language and the service of language. It began as a response, as a form of thinking about ‘resistance’ and ‘protest’ as a form of love. I thought of love songs and the type of incantation or refrain that they is often embedded in the songs. Many of the refrains I found could also be isolated and thought of in terms of pleas or protest. These phrases, these refrains, are the ones I chose to use in this project. The use of ribbon and fabric assembled in a woven form reminded me of clothing and of decoration. The banners could be used, could be held up, could be carried.

Meital Yaniv

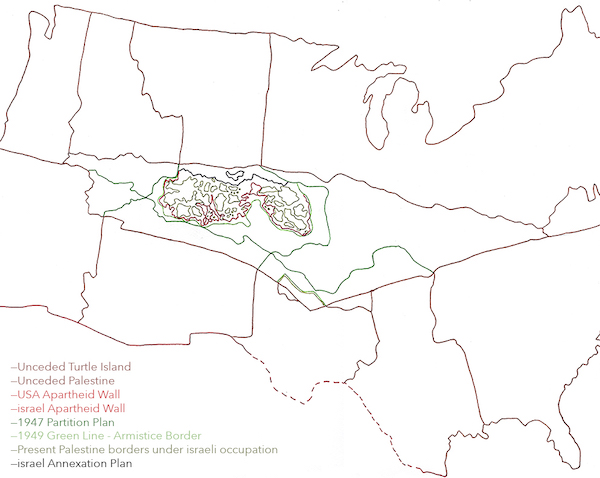

Meital Yaniv, 2020, Bloodlines, pen on paper, 35 x 27 cm

When assimilation is understood as a means for survival the imprint of erasure becomes a lifeline. The tension in the body eliminates any association with the comfort of a root—a tradition—a culture—a language. Through the generations things are not only hidden but completely erased. We do it as a people because we believe that is the only way we can survive; we do it as a people to protect our young ones, to become one with the dominant culture. Assimilation takes away the knowing of home one has in their own body, it creates a need to find a material home away from the body knowing. Jews exploit Black people to assimilate into white America, Jews exploit Palestinian people to assimilate into white israel. israeli jews’ standard of beauty became one with their oppressor’s standard of superiority; aryan—blonde—blue—white. Adding to that the brainwashing and conditioning of the imperialistic North American dominant culture has quickened the deepening of white supremacy into the israeli culture. The root of the word justice in Hebrew also means being right; zedek צדק. When was the moment when assimilation interfered so severely with our fight for justice that we settled on revenge? The moment we became the oppressor because we lost the sense of home in our bodies, we lost the root of our fight for justice. A material home in a capitalist, racist, patriarchal, able society demands to be defended by force. If the white race was invented to justify the enslavement of Black people, what did the invention of an israeli identity justify?

Ken Gonzales-Day

Ken Gonzales-Day, 2014, Unidentified protester facing police line, Los Angeles, photograph

The photograph was taken in Los Angeles during the protests and marches that took place in the days following the Grand Jury’s decision not to indict Darren Wilson, the white police officer involved in the shooting death of Michael Brown, the unarmed black teen that became a focal point for many in the Black Lives Matter movement which has since grown to become a truly global movement.

Alexander Kritselis

Alexander Kritselis, Fractured Realities 2020- Democracy Project, installation with various objects, neon lights, and charcoal on arches paper 72” x 240” x 48”

Democracy is been fractured. Unbridled interpretations of constitutional powers and unprecedented access to communication platforms endlessly carrying streams of information have cracked the lens of perception causing the simultaneous existence of diverse realities flaunting their contempt on equality, representation and fairness and testing the resilience of the twenty-five-century old democracy project. My installation, “Fractured Realities 2020”- Democracy Project”, startles a world where one encounters the same space straight on and in reverse. In each version, behind a hokey game of death played over a mount of mutants reaching for the light, the two main characters carry different items representing promise, captivity, temptation, distortion, ridicule, light and sugar.

Sama Alshaibi

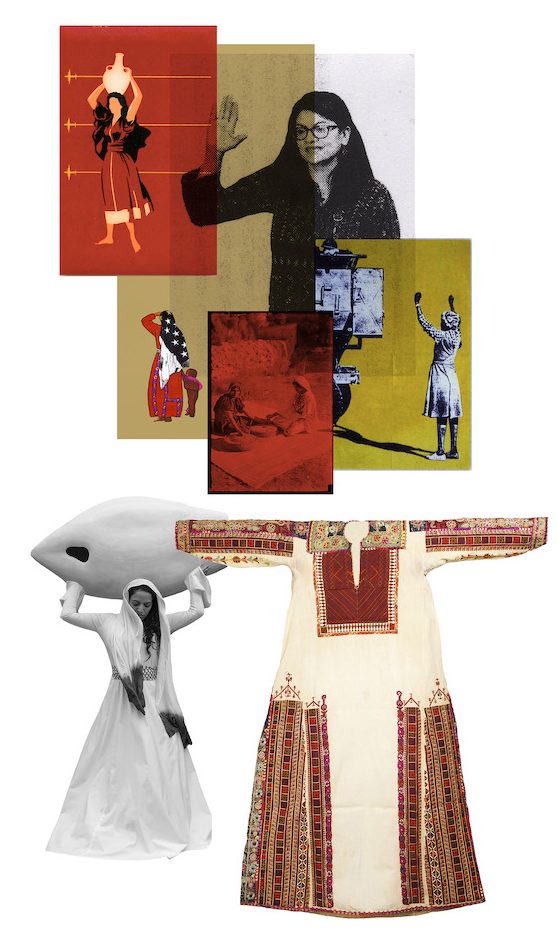

Sama Alshaibi, Adjudicating the Jezebel, archival digital print (or textile mixed-media), 48″ x 24″ The artist acknowledges Park Avenue Armory for development support in association with the creation of this work.

Adjudicating the Jezebel reflects the current moment and American history for women, immigrants and people of color. The image contains motifs inspired by Congresswoman Rashida Tlaib’s tunic dress, a Palestinian embroidered thobe, worn to her 2019 swearing-in ceremony at the U.S. House of Representatives. The 2018 United States Midterm Election was historic by several measures. Occurring during the presidency of Donald Trump, it contained several electoral firsts for women, racial minorities and LGBTQ candidates. Among these many firsts was a victory for Rashida Harbi Tlaib of Michigan’s 13th Congressional District. She was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, as one of the two first Muslim-American Congresswomen and the first Palestinian-American to hold the office. Her victory was also hailed as part of a new wave of progressive leftist women of color who challenged the Democratic Party establishment—from Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in New York City to Ilhan Omar in Minnesota, and aided by unpresented turnouts of women voters across the United States. However, the controversy and criticism of Congresswomen Tlaib, Omar and Cortez continue to illuminate the difficulties in ‘being first’, especially for women who are persons of color. At times, they are held up as saviors of the party, and at others, transgressive women who dare to challenge the status quo. As a Palestinian-Iraqi American artist, the Palestinian thobe has featured prominently in my work as narratives of identity, maternal lineage, resilience and women’s labor. I collaged the Palestinian embroidery patterns, historic political posters of resistance and my own photographs to construct a tension between cultural identity, gender and intersectional feminism seen in the 2018 election. The trailblazing paths of Tlaib and women like her honors the sacrifice and labor of the suffrage movement, and the enduring fight for a democracy that serves us all.

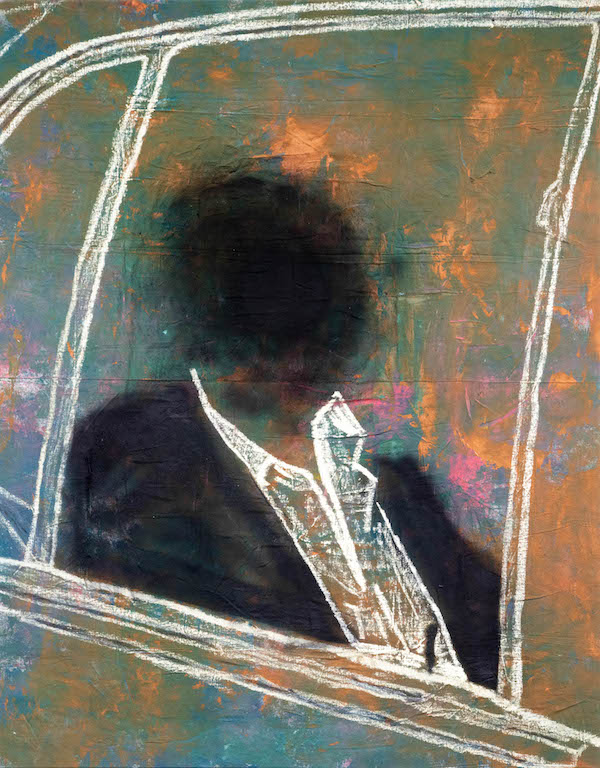

Salim Green

Salim Green, 2020, Hinckley, oil, acrylic, and spray paint on drop cloth, 62” x 48”

Salim Green (b. 1996) explores surrender and what it allows. “Hinckley” is an exercise in memory and sense making within this bizarre democratic republic we’ve happened in. How do we bridge the gaps between personal history, collective history, and imagined history?

Antoine Girard, 2020, independent curator and director of community relations at The Underground Museum, LA. Girard will curate an exhibition for Deitch Projects this February.

Lawrence Gipe is an artist and independent curator working in Los Angeles. His latest solo exhibition was at Tsinghua University in Beijing, China, late last year.