For this democratized issue of Artillery, I’ve decided to focus on the most democratic medium of art: graffiti. Graffiti is as diverse as any medium but, generally, it is the painting of text or images onto surfaces in public spaces. The operative word in that definition is “public;” these works of art are able to be viewed and enjoyed (or scorned, for some) by anyone who happens to see them. This puts graffiti miles ahead of any gallery or museum in terms of democratic access. Museums have long had an issue with access, and besides their self-definitions as public storehouses of culture, they have consistently missed that mark. Not only do the majority of museums exclude those that do not have the money or time to visit a museum, but they are also historically white, heteronormative, and masculine spaces. Graffiti, purely by the virtue of its public setting, defies those labels; there is no context to put graffiti into other than society itself.

When I say graffiti, I am specifically avoiding terms like “street art” or “murals.” While they are similar in their public accessibility, there is a critical difference. That difference is that graffiti is both never commissioned nor later sanctioned and absorbed into the world of fine art. You can’t put graffiti into a museum or sell it at an auction house—no matter what Banksy does. Graffiti is unbounded by traditional art-world mechanisms and therefore has the chance to transcend the traditional “purposes” of art. It inherently responds to the situation of its creation, and doesn’t require explanation or clarification. And the artists are anonymous, or at the very least use a pseudonym. Moreover, these artists are members of your community, members who have felt so profoundly the urge to create and voice their ideas that they risk fines or arrest just to put it up on a wall. If paintings in a museum are whispered conversation at a gathering of elites, graffiti is shouting from the rooftops with a megaphone called spray paint. And this megaphone can be very compelling and beautiful if you give it the chance to be.

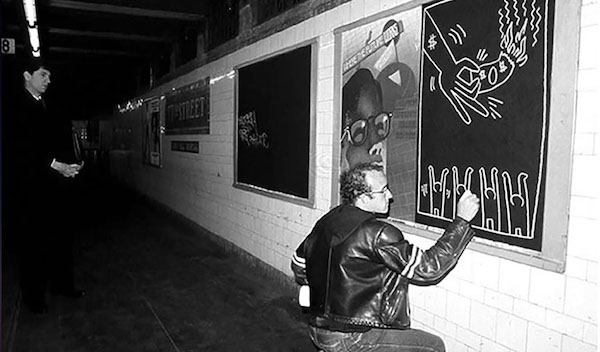

Keith Haring creates art in a public subway station in 1980.

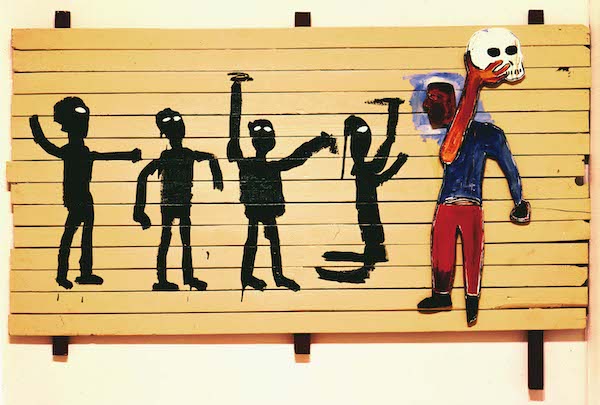

Keith Haring—who, along with Jean-Michel Basquiat shaped the world of graffiti in New York and internationally during the 1970s and ’80s—wrote in his journals about museum access. He believed that museums overlooked large sections of society, who were “ignored, but not necessarily ignorant.” It’s a very shameful misjudgment to believe that those who don’t frequent museums or galleries are unable to appreciate art, or that the only art worth appreciating is found in those places. For me, graffiti adds to the visual appeal of a city, and once you start viewing graffiti as art, the city around you transforms into a canvas. So the next time you see graffiti, don’t worry about the walls they’ve used—appreciate that some brave person dragged art out of the sanitized white walls of the museum and onto the street for all to see.

0 Comments