I love most animals, in fact pretty much all animals, including some species especially hostile to human life (maybe those most of all). But I’m not one to fetishize them – or many other things, either (I think). However, whether it’s because of social media or just word on the street getting around (I guess that pretty much means social media nowadays), a lot of people – not just my close friends – know I always have a cat or two (or more?) around my household. It has nothing to do with them being cats, per se. I mean it could be a dog or a horse (Shetland pony?), or a turtle (or other reptile), or a squirrel or ferret, or whoever else (non-human) drops in for dinner and overstays their welcome.

Anyway, whether I go get them, or they come get me, they usually stick around and at some point become integral to the way my household functions. (That’s a laugh line for my pals and a warning to anyone else.) I’ve written stories about my various relationships with my feline children & feline/canine/equine/reptile, avian and aquatic nieces and nephews because they’ve been some of my closest and most vivid, and have made for some of my best experiences outside of Disney and Carnegie Halls and the city of Paris.

If the choice is between an art show and live music, my choice is almost always music. Art shows are usually up for at least a few days, while the live performance can never be duplicated. If the art show has an overtly commercial concept or the work/themes threaten to veer into toxically cute, my decision is that much easier.

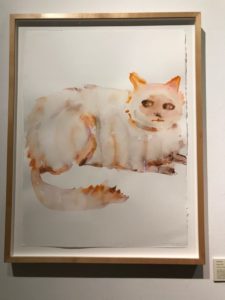

Kim McCarty, “Fat Cat” (2018)

So the show on tap was the third biennial edition of curator Susan Michals’ Cat Art Show. I missed the first couple, so for all I knew I could be walking into a Siegfried and Roy revue gone way off the track. (Not necessarily a bad thing right there. Siegfried and Roy were and are truly great artists.) The bill across town (an art space by the way – LAXArt) was Kim Gordon – who rarely disappoints. But Susan Michals is a smart curator and two or three of my favorite people had charmed me into promising to drop by for a minute or two with the promise of libations and … well, … cats.

Everyone remembers the famous Goya portrait of Don Manuel (Zuniga? – I forget the rest) from the Met. And who could be bothered remembering the name when you have that tabby all but stealing the show from that elegantly attired lad? It’s the joke that makes the picture work so charmingly (or maybe alarmingly) – the boy thinks he’s running the show, while the cat has his eyes lasered onto that magpie Don Manuel has apparently let out of its cage for a constitutional. Poor frustrated cat! Poor threatened bird!

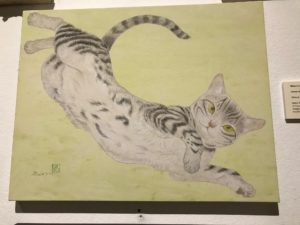

Midori Furuhashi, “Green Breeze” 2013 (Mineral pigment on wood panel)

Though that’s the thing about cats – they’re never drama queens. They linger at the margins (sometimes literally – you can occasionally see feline figures in the marginalia of medieval illuminated manuscripts). They amuse themselves; they distract themselves with games (sometimes involving smaller prey). Sometimes they’re not even awake, napping in baskets or curled at the feet of some once-great personage (or simply wandering in from the background). Yes, once great and never to be heard from again – sic transit gloria mundi. But the cat lingers on … with its ‘pale blue (or green, yellow, amber, etc.) eyes’. Our eyes always find a way to them – as if they hold the secret to this pictorial alchemy. But if they do, they hold it close, yielding nothing without due recompense, and not even then – making us draw an occult inference from their gaze, their parsimonious vocal expressions, their purring, the flick of their tails. We want them more than they need us. It’s no wonder we once worshipped them. They were the original bodhisattva; they were definitely the original muse.

We may be moving back in that direction (and goddess only knows we might have seen that coming – except for the Baroque architecture they once inspired, human-inspired deities have been pretty much a continuous disaster, culminating in our current eco-catastrophe). We’ve always observed (and exploited) the animal world for the reflections of our imprint on the physical environment and our imagined, reconceived or invented, or virtual recreations of it; and cats have always been a sketchbook staple, the subject of every variety of graphic art. But in recent decades, artists have given rein to cats – their own, their imaginary or idealized feline muses, or more abstracted feline inspirations – to wander in from the wings and take center stage. I’m not sure if this began with Warhol’s ‘25 cats name Sam, and One Blue Pussy.’ The nature of our relations with cats (which has also changed subtly over the last half-century) has made them the vehicle of unspoken (and occasionally unspeakable) thoughts, fears, apprehensions, desires and aspirations.

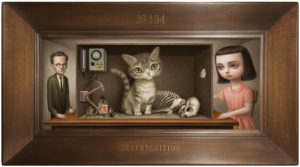

What amazed me most about The Cat Art Show 3 was that most (if not quite all) of the artists on view rose to the challenge of mining those observations and inspirations with considerable originality, verve, virtuosity, and even brilliance. There were some 140 works on view and one was drawn in for a close look at almost all of them. This is not something to be expected, even in a museum show. My initial expectation was that I’d be walking into a few gems amid a sea of quasi-pop/commercial ‘low-brow’ art. (I don’t like the term ‘low-brow’, and I think it’s occasionally misapplied; but I think readers will know what I’m talking about.) In this particular instance, even what might be shoved into that category managed to be pretty brilliant. Mark Ryden’s rendition of the famous “Schrödinger’s Cat” quantum mechanical ‘thought’ experiment, Superposition, managed to brilliantly sum up the spirit of the entire show and perhaps the entire scope of human endeavour as it is tenuously connected to the feline world. It also connected with the moment we’re living through (which on that particular evening seemed especially dark to me). Which is to say that the best work in the show captured those simultaneous moments, those dual (or multiple) universes contained within the special domain we share with cats or evoked by them.

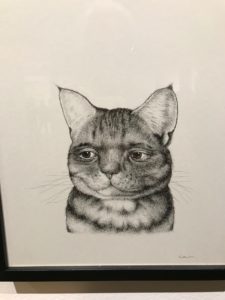

A number of artists are conscious of the extent to which their cat subjects are really a kind of anthropomorphic or even self portraiture. Michael Caines’ work falls into this category, but also reminds of the way we see feline character articulating itself in the course of our relationships with them, as well as the way we see ourselves in our cats; or still more generally the way we can project specifically feline character or characteristics upon human subjects. This subject happened to be Clarence (pen and India ink on paper, 2015) – whether a cat with human eyes or human with a cat face, we can’t be sure – but I think I’ve seen him in an old movie. But as I’m sure (whether cat or human) he’s trying to remind us: never try to second-guess a cat.

A number of artists are conscious of the extent to which their cat subjects are really a kind of anthropomorphic or even self portraiture. Michael Caines’ work falls into this category, but also reminds of the way we see feline character articulating itself in the course of our relationships with them, as well as the way we see ourselves in our cats; or still more generally the way we can project specifically feline character or characteristics upon human subjects. This subject happened to be Clarence (pen and India ink on paper, 2015) – whether a cat with human eyes or human with a cat face, we can’t be sure – but I think I’ve seen him in an old movie. But as I’m sure (whether cat or human) he’s trying to remind us: never try to second-guess a cat.

The exhibition was superbly indexed and documented and the texts bore out much of what I read into some of the subjects. Travis Louie works in a similar and no less deadpan vein as Caines, but far more fantastically, almost hermetically. His acrylic painting on board was presented in a traditional oval dark wood frame, with convex glass and you felt that was exactly where it belonged. What it looked like was a wry, sober, slightly ironic (if still gamine) version of a familiar character – the Dr. Seuss “Cat In the Hat.” The grisaille – not a bit of color – set the mood; and the title set us straight: Dreams of a Moss Covered Three Handled Family Gredunza. I can’t add anything to this description, which I thought was perfect:

The exhibition was superbly indexed and documented and the texts bore out much of what I read into some of the subjects. Travis Louie works in a similar and no less deadpan vein as Caines, but far more fantastically, almost hermetically. His acrylic painting on board was presented in a traditional oval dark wood frame, with convex glass and you felt that was exactly where it belonged. What it looked like was a wry, sober, slightly ironic (if still gamine) version of a familiar character – the Dr. Seuss “Cat In the Hat.” The grisaille – not a bit of color – set the mood; and the title set us straight: Dreams of a Moss Covered Three Handled Family Gredunza. I can’t add anything to this description, which I thought was perfect:

“Travis Louie … has created his own imaginary world that is grounded in Victorian and Edwardian times. It is inhabited by human oddities, mythical beings, and otherworldly characters who appear to have had their formal portraits taken to mark their existence and place in society. The underlying thread that connects all these characters is the unusual circumstances that shape who they were and how they lived…. [H]e has created portraits from an alternative universe that seemingly may or may not have existed.”

And you thought you knew The Cat In the Hat?

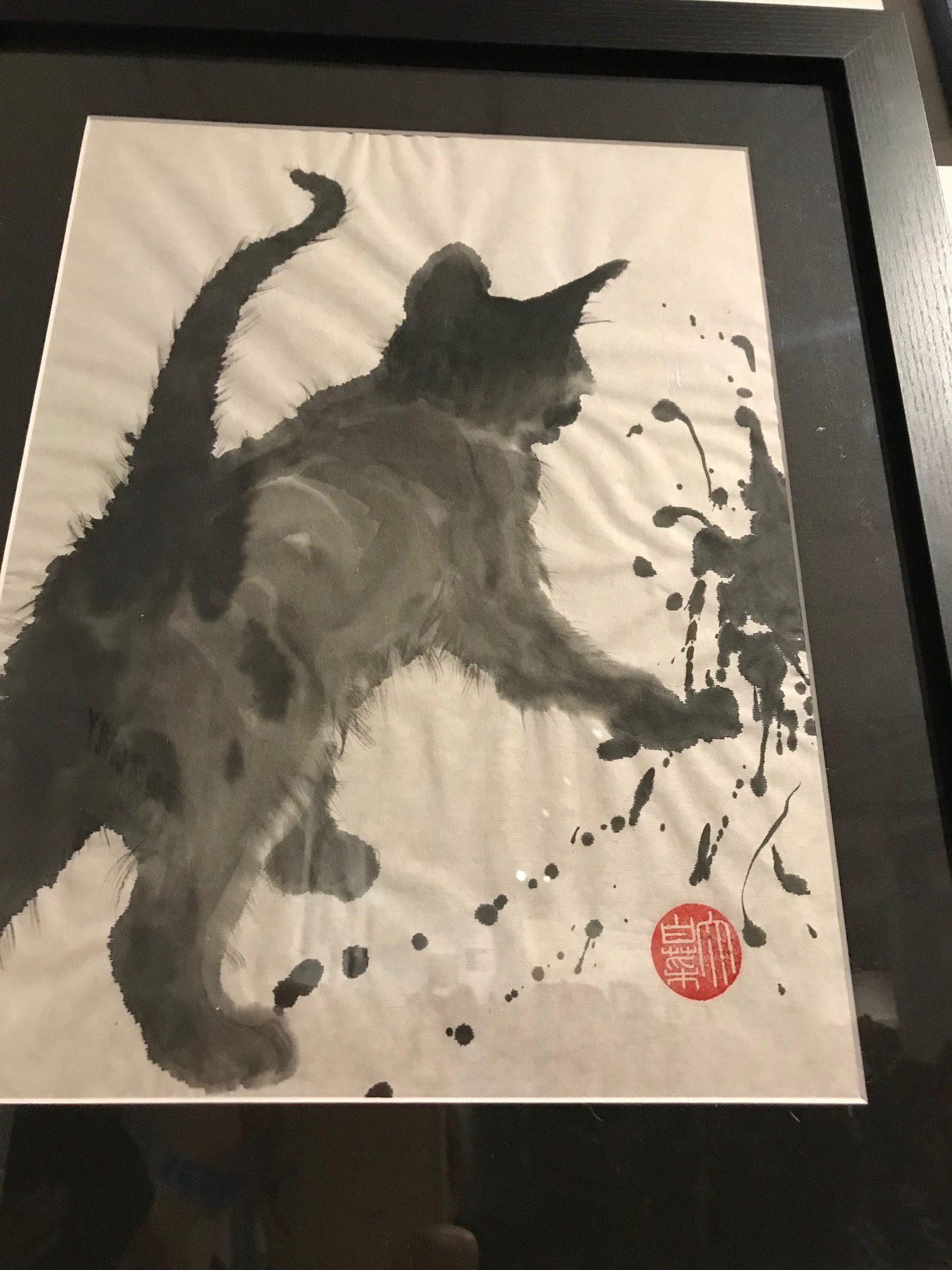

I sometimes wonder if I’m guilty of ethnic/cultural stereotyping given what I view as a particularly Japanese affinity for the harmony of the natural world. (Their natural environment has certainly been no less turbulent; but their art seems to achieve a resolution, even serenity that Western art rarely approaches.) But Japanese artists have a special gift for eliciting the natural magic cats are capable of radiating in almost any situation. It can range from the most quotidian domestic observation to something that approaches transfiguration. Katsunori Miyagi understands how to deliver that moment seemingly transfigured beneath the (literal) wash of our gaze. His cats, with dramatically highlighted markings, sit, stand or hang beneath undulant Rothko-esque watercolor washes in slightly opalescent tones that reminded me as much of some of Eva Hesse’s latex constructions as Rothko’s paintings – the chromatic subtlety in every way stands up to their masterly draughtsmanship. I could easily revisit the show just for these paintings.

I sometimes wonder if I’m guilty of ethnic/cultural stereotyping given what I view as a particularly Japanese affinity for the harmony of the natural world. (Their natural environment has certainly been no less turbulent; but their art seems to achieve a resolution, even serenity that Western art rarely approaches.) But Japanese artists have a special gift for eliciting the natural magic cats are capable of radiating in almost any situation. It can range from the most quotidian domestic observation to something that approaches transfiguration. Katsunori Miyagi understands how to deliver that moment seemingly transfigured beneath the (literal) wash of our gaze. His cats, with dramatically highlighted markings, sit, stand or hang beneath undulant Rothko-esque watercolor washes in slightly opalescent tones that reminded me as much of some of Eva Hesse’s latex constructions as Rothko’s paintings – the chromatic subtlety in every way stands up to their masterly draughtsmanship. I could easily revisit the show just for these paintings.

I never actually saw the (untitled) Raymond Pettibon that was on view, subtitled In the catbird… (2017), but I thought Gosha Levochkin caught something of Pettibon’s spirit and animus (perhaps with a dollop of Paul McCarthy at his most acidulous) in his 2018, PUSSY. In a way, this seemed something of a departure for Levochkin, whose eclectic, graphic, superflat work lends itself almost perfectly to animation – but gives a sense of his capacity for acute, satiric observation.

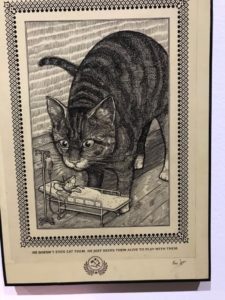

Like Miyagi, Ravi Zupa also draws on long tradition of animal and natural imagery, which though conceivably centered in India’s Mughal legacies, has ranged far afield into a global spectrum of graphic art, from (according to the legend/index card) German Renaissance printmaking to Japanese woodblock, Pre-Columbian art and agit-prop. The text may have strayed a bit far from Zupa’s intention for this particular and more-than-a-little-ironic drawing, Playtime (India ink on paper, 2018). What Michals, et al. clearly intended to underscore was the global-minded Zupa’s much broader disdain for puerile attempts at ‘ironic’ cultural appropriation.

Like Miyagi, Ravi Zupa also draws on long tradition of animal and natural imagery, which though conceivably centered in India’s Mughal legacies, has ranged far afield into a global spectrum of graphic art, from (according to the legend/index card) German Renaissance printmaking to Japanese woodblock, Pre-Columbian art and agit-prop. The text may have strayed a bit far from Zupa’s intention for this particular and more-than-a-little-ironic drawing, Playtime (India ink on paper, 2018). What Michals, et al. clearly intended to underscore was the global-minded Zupa’s much broader disdain for puerile attempts at ‘ironic’ cultural appropriation.

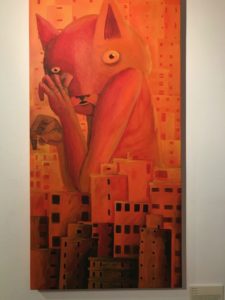

Thiago Goms’ ‘cats’ – definitely of the anthropomorphic variety, really humans with cat heads – hearken back to the graphic work of German post-expressionist and Weimar ‘new objective’ graphic artists. Here his cat-men seemingly tremble amid the concrete jungle of abstracted cityscapes no doubt inspired by the São Paulo of Goms’ childhood.

Thiago Goms’ ‘cats’ – definitely of the anthropomorphic variety, really humans with cat heads – hearken back to the graphic work of German post-expressionist and Weimar ‘new objective’ graphic artists. Here his cat-men seemingly tremble amid the concrete jungle of abstracted cityscapes no doubt inspired by the São Paulo of Goms’ childhood.

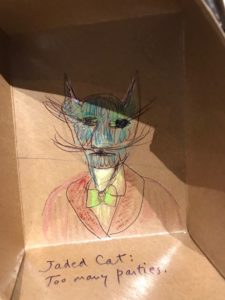

Can we even wonder whether cats sense our own anxieties about our worlds – nature, or more precisely our loss of it, the intrusion of technology into our everyday actuality, our uncertainty about our purchase on it all? Kathy Taslitz’s Pussy Anxiety (2018) speaks to these issues directly and articulately. (While Michael Lindsay-Hogg (Jaded Cat, 2018) reminds us how sick of us they must occasionally get.)

Can we even wonder whether cats sense our own anxieties about our worlds – nature, or more precisely our loss of it, the intrusion of technology into our everyday actuality, our uncertainty about our purchase on it all? Kathy Taslitz’s Pussy Anxiety (2018) speaks to these issues directly and articulately. (While Michael Lindsay-Hogg (Jaded Cat, 2018) reminds us how sick of us they must occasionally get.)

It’s almost impossible not to notice our cats’ sensitivity, their sixth sense about our movements and habits, our troubles, plans and schemes. And – especially if they move between the domestic space and their neighborhoods – we know they have a sense of the environment probably no less informed than our own. I could go on ad nauseam about so much of the brilliant work in this show by artists including, in no particular order, Anita Wong, Lauren Benrimon, Yael Hoenig, Kim McCarty, Tasya Van Ree, Lisa Lebofsky, Paul Koudounaris, Laura Keenados, Perrin Lam, Scott Hove, Midori Furuhashi, Adipocere, Kelly Berg, Mari Shimizu, and Charlie Becker. But I think we all get how lucky artists (and the rest of us) are that cats wandered in from the cold or the heat and into our still-precarious earth-bound encampments. I’m just cat-damaged enough to hope they can persuade us to keep it going.

It’s almost impossible not to notice our cats’ sensitivity, their sixth sense about our movements and habits, our troubles, plans and schemes. And – especially if they move between the domestic space and their neighborhoods – we know they have a sense of the environment probably no less informed than our own. I could go on ad nauseam about so much of the brilliant work in this show by artists including, in no particular order, Anita Wong, Lauren Benrimon, Yael Hoenig, Kim McCarty, Tasya Van Ree, Lisa Lebofsky, Paul Koudounaris, Laura Keenados, Perrin Lam, Scott Hove, Midori Furuhashi, Adipocere, Kelly Berg, Mari Shimizu, and Charlie Becker. But I think we all get how lucky artists (and the rest of us) are that cats wandered in from the cold or the heat and into our still-precarious earth-bound encampments. I’m just cat-damaged enough to hope they can persuade us to keep it going.

The Cat Art Show 3 runs through this week-end at Think Tank Gallery downtown – and Cat fanciers may gather for an early closing party tonight. Your cats will excuse you if you leave them at home alone for one evening. They always do.