By the time my studio visit with Francesca Gabbiani is winding up, the conversation has turned to Griffith Park. We talk about our respective walks, and various neglected areas of the Park—the depleted bird sanctuary and abandoned spaces and cages near the Zoo—and the spirits that haunt those spaces. Gabbiani became obsessed with the dark history of the Park’s benefactor, Griffith J. Griffith. Less than a decade after the 3,000-acre bequest that became his namesake park, he nearly killed his wife, Christina, by shooting her in the eye, leaving her permanently disfigured—a crime for which he served two years in prison.

Something of Christina’s spirit may remain in the park; but our fascination speaks of a more extensive legacy of human and wild life marking the landscape. Coyotes can occasionally be heard howling in the early evening and their alarm signals a warning beyond their dark sanctuary.

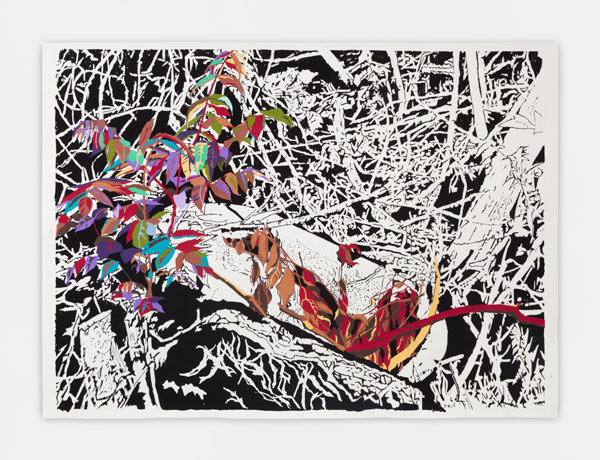

You sense the “call of the wild” in Gabbiani’s work, even through its intense artifice and deliberation. Beyond the elaborate mapping and breakdown of the image (whether physical landscape, domestic or interior space, or what we might just call the dark vortex of the imagination) preparatory to its rendering in the cut colored papers and various pigmented media (inks, gouache, watercolor, acrylics) she has made her signature, her process is a decoding and recoding, a continuous reconsideration of places, their constituent phenomena, and what we might call, in perceptual terms, their “aura.”

Situated on the flanks of Atwater Village, Gabbiani’s studio has the feel of a refuge on the gray day I visit her. We trade notes about some of the shows we’ve taken in the night before—and I’m not at all surprised to hear she admired the same John Divola “running figure” photographs I did at a downtown gallery. I mention the abandoned, vandalized shacks, sheds, boathouses and the like Divola brought to vivid life in the late 1970s that resonate with Gabbiani’s recently exhibited work. “He’s done that in photos and I have, too.” Gabbiani’s view takes a broader, exteriorized view in this work, but it is the continuity with her earlier work I pursue in our conversation.

Destruction of a Radical Space, 2015.

Gabbiani has fixed her eye upon many film-worthy houses and domestic interiors since her arrival in Los Angeles in 1995. At one point in our conversation, she mentions one of the first she sighted driving around Los Angeles—an “Asian-looking house” that appeared in John Cassavetes’ 1976 film The Killing of a Chinese Bookie. As I follow her around the studio, the movie pedigree of other images from past works or works in progress is disclosed—between fires, a subject she returns to in her most recent work (“spectacles, I call them”)—an ironic segue from the surreal horror films and LA film noir that have been a constant inspiration in her work. “This is a real house on fire—well it’s actually a dollhouse from [Terrence Malick’s 1973 film] Badlands.”

The darkness goes back as far as the abandoned houses and spaces she once occupied as a squatter after leaving school in Geneva. “There were all these empty spaces. They were very dark; the staircases could break, but all those empty houses and spaces became a refuge.”

Dead Nature with Bathtub, 2017

The tenuous refuge or sanctuary is another through-line in her work—the disused or abandoned site that becomes a vehicle of transformation. “Why is it a refuge even though it’s scary?” She returns momentarily to Bachelard’s notion of the “attic or cellar” that might be regarded as a nest; and “why does it feel like home? I can stay there because I can change it maybe.”

“I kind of make it fantastical.” Gabbiani trails off here, but seems to confirm the connection between tenuous sanctuary and the elements of fantasy, even horror, that might be invited in right alongside. “I’m interested in the ephemerality of those spaces,” she says, “if there is an ephemerality to them.”

Installation view, Vague Terrains/Urban Fuckups, Gavlak Los Angeles, April 13–June 9, 2018 ), courtesy of the artist and Gavlak Los Angeles / Palm Beach.

The fire in one sense or another has never been far off. Gabbiani has been no less moved by the “spectacle” of the recent wildfires and their destruction than the rest of the city, and she recently turned her attention to the aftermath of the burn—not so much the charred landscape that might be yet another black ground, but the smoke and miasma of debris clouding the atmosphere. “I’m trying to work on smoke. There were a few times I’d been on hikes when the mountains were on fire; and I’d be looking at mountains surrounded by smoke. So how do I do smoke?” Gabbiani shows me an array of fragments in sfumato variations—smoky indigos, blue-grays and inky blacks, mostly in watercolor and gouache. The atmospheric studies become a fresh groundwork for “the fluidity of the paint and the opacity of the paper” on a technical level, and perhaps an exploration of chaos—a systemic ephemerality on another level.