A lot has changed since 2011, when Maggie Nelson first published The Art of Cruelty: A Reckoning, her critically acclaimed collection of essays addressing violence and transgression in avant-garde art.

One thing that’s changed is the word “trigger”—now much more widely used to indicate a word or image that a traumatized individual might find so upsetting that it threatens their mental health. This seven-letter word’s second life is a surprisingly useful piece of linguistic technology, as it cleanly separates (and assumes a separation between) the possibility of inadvertently causing pain to an individual from social harm. I know someone triggered by spiders, I know someone triggered by buses, neither see a need to excoriate the continued existence of public transport or class Arachnida.

Nelson writes too early to rely on “trigger,” but she might’ve saved herself a few paragraphs if she could have: The strength of her book is that it frames the “reckoning” in the title as personal—she frames the confrontations of confrontational art as with individuals, she frames her reactions as her own. Like David Hockney’s book, That’s The Way I See It; it doesn’t demand you agree with it for it to be interesting.

Nelson starts from neither end of the nihilist-libertine-to-moral-scold spectrum; she’s a person who once called someone to register her outrage about a billboard advertising a horror movie and a person who read and enjoyed the Marquis De Sade and then did the only interesting thing someone like that can do: ask why? Artist-by-artist, piece-by-piece, movement-by-movement, Nelson bangs her head against her own reactions. She does what so many critics fail to: she feels, but then does something else afterward. This requires acknowledging that the difference she sees begins in her own history and nervous system, rather than in a measurable world of cultural certainties. She takes the pre-eminent activist-critic John Berger to task for his attack on Francis Bacon’s blood-soaked pessimism as the work of a “conformist” trying to “persuade the viewer to accept what is”:

The problem here, it seems to me, lies in Berger’s willingness to give Bacon’s proposition such overarching power. For while the paintings may indeed propose that there is nothing else, their proposition remains just that—a momentary proffering. As one beholds them (at, say, Bacon’s 2009 centenary retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art), there is wall space between each canvas, there is space to walk around the room. One can come and go, look closely, then look away, stay for a long time or simply walk on by, en route to the bathroom or gift shop. Their depiction of belatedness or mindlessness—however claustrophobic—does not necessitate our acquiescence. They are paintings; our job is to behold them. There is no need, or even invitation, to submit to their terms.

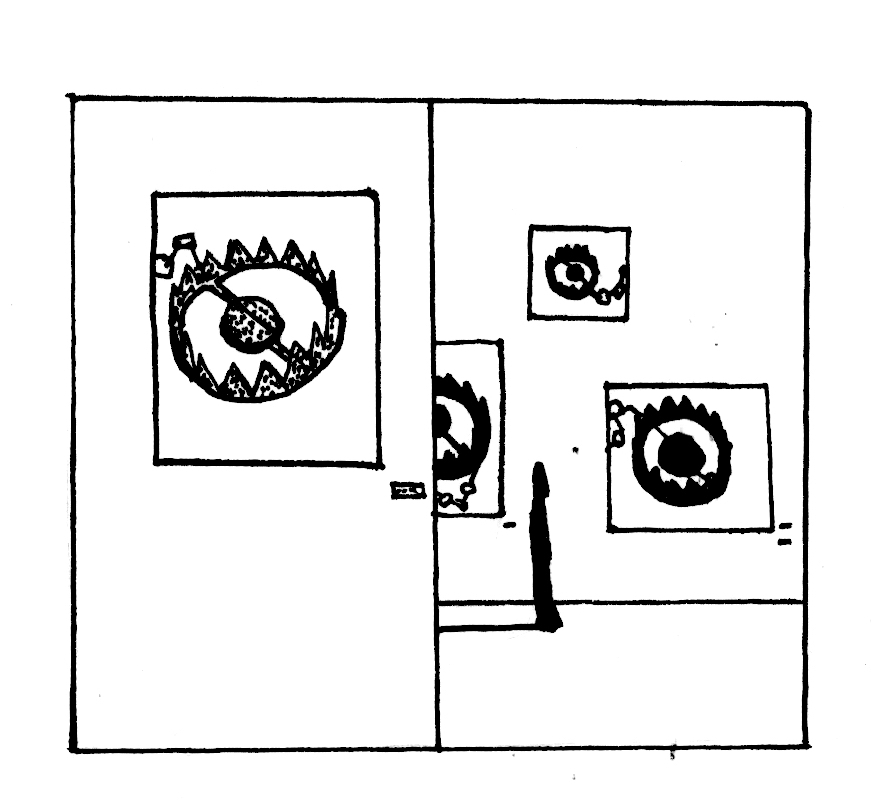

This decade-old observation about a painter 30 years gone hits today with such force because of another thing that’s happened since Nelson published this study of a handful of works she rubricked together under the Art of Cruelty umbrella: All art is cruel now. Or rather examining art for its cruelty-quotient is the pre-eminent critical tool. There are a great many advantages to this approach—if a piece you never liked anyway can be proven to be cruel, the more difficult, nuanced and queasily subjective work of arguing why you never liked it can be skipped. It’s hurting people get rid of it. Conversely, if a work you like can be pronounced (as if it were lip-gloss) cruelty-free then anyone arguing merely that it might not be enjoyable or interesting can be consigned to the pale Hell of the cruelty-apologist. The languid vagaries of aesthetic judgments can be abandoned for the undeniable urgency of moral ones.

Nelson refuses to take that bait, acknowledging the difficulty of disentangling the two in, for example, her take on avant-horror author Brian Evenson:

…his writing doesn’t just evoke the precision of slicing or cutting; his characters actually perform the deeds. When this literalness works, the work carries both visceral punch and intellectual heft. When it falls short, either the violence or the concept behind it seems suddenly naked, paltry, wrong. It is, in short, a gamble.

Granting the artist the right to gamble is a powerful act of critical humility, saying: you can try, you can fail, and if you do, you’ve failed only Maggie Nelson, not the whole of humanity. We need a world less willing to hide behind a crowd.