The first to grow up in an image-centric world where the mass-dissemination of images via film, print and television started to infiltrate American culture on scales never before seen, those of the Pictures Generation found themselves grappling with notions concerning authenticity and authorship. Immersed within a world where the affluence of representation was starting to reveal its impact upon the collective consciousness, many of these artists began looking to appropriation as a vehicle to analyze their relationships with popular culture and the mass media.

Of particular influence here were Michel Foucault and Roland Barthes, whose philosophical writings cultivated a shift in literary discourse. By encouraging the reader to divert his attention from the author’s intent and instead impose his experience onto a text’s meaning, they fostered a similar shift in art criticism. Many of the “Pictures” artists embraced this tenet by subverting the signifying functions that popular imagery imposed by appropriating recognizable and often iconographic images. In doing so, they didn’t just elevate photography as an art form, but ultimately changed the way we look at pictures.

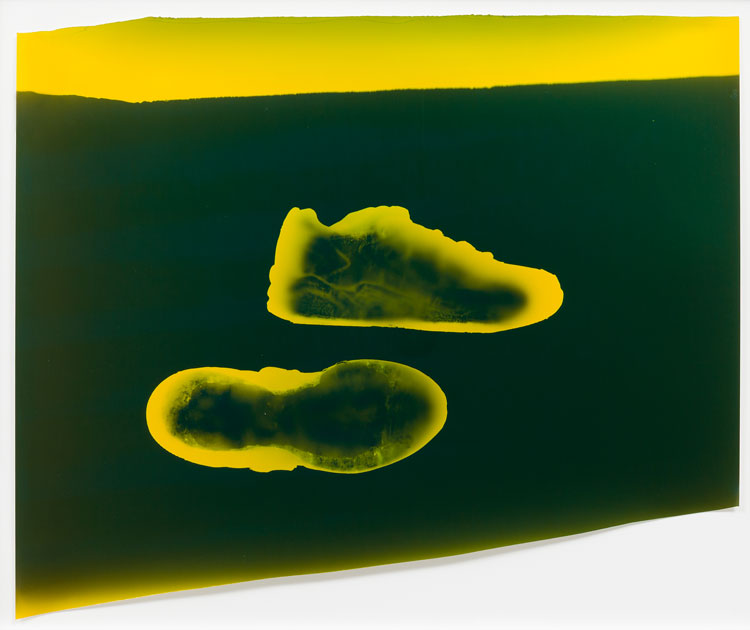

Floris Neusüss, Sonn (1), 1998, photogram, 16 3/8 x 11 ½”, unique, courtesy of the artist and Von Lintel Gallery

The same can be said about a number of contemporary photographers who are returning to the darkroom and revisiting analog technologies for their capacity to capture the mercurial effects that conspire when material properties interact. “In what could be described as a reaction to all things digital,” says LA gallerist Thomas von Lintel, there’s been “a steady proliferation of younger artists embracing older photographic processes, such as photograms, cyanotypes, gum prints or tin types, just to name a few.” While the “Pictures” artists inspired a new discourse by undermining old notions about photography, artists today are doing the same by embracing the mistakes and chance happenings that are apt to result from the imprecise science upon which photography was founded.

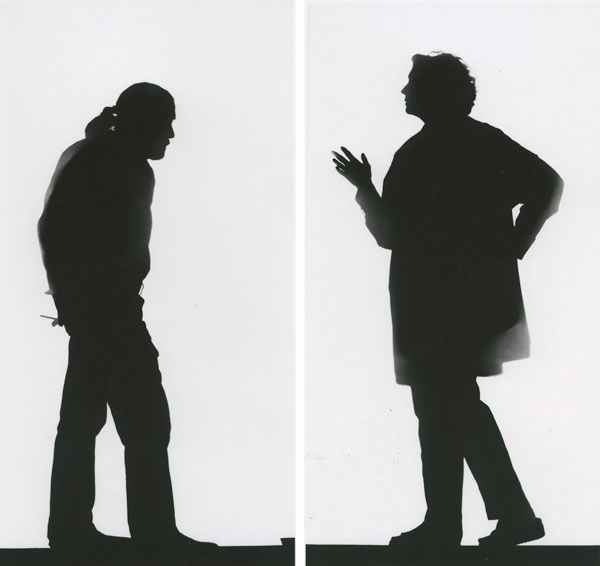

The lineage of aesthetic influence here dates back to László Moholy-Nagy and Man Ray, who revived the camera-less photogram technique in the 1920s as a means for exploring the expressive properties of light. During the mid-19th century, the photogram process was revisited again by Floris Neusüss, whose camera-less Körperfotogramms captured life-size silhouettes of nude bodies exposed on photographic paper. Along with Pierre Cordier, who invented the chemigram technique in the 1950s, Neusüss cultivated a new regard for photography and its role as an artistic medium, which practitioners such as Robert Heinecken celebrated by incessantly testing the medium’s limitless possibilities.

Floris Neusüss, Portrait of Robert Heinecken; Portrait of Joyce Neimanas, 1997, Gelatin silver photogram on auto-reversal paper, Unique, courtesy of the artist and Von Lintel Gallery

Heinecken, whose provocative camera-less works have likened him to Robert Rauschenberg due to his innovative mingling of painting, sculpture and printmaking with photography, established UCLA’s photography department in 1964. At the time, the department’s innovative and experimental approach to photography was groundbreaking and ultimately set a precedent. Among the many who have benefited from Heinecken’s lead, and are placing their focus on the tangential nature of the photographic process, is James Welling. While his initial investigation with the materiality of photography associates him with the Pictures Generation, his move to Los Angeles in 1995 to head UCLA’s photography department significantly shifted his relationship to the art form.

Floris Neusüss, Nachtbild (65), 1988, photogram, 21 3/4 x 20”, unique, courtesy of the artist and Von Lintel Gallery

When Welling began experimenting with the photogram technique, he found that it fueled his ongoing obsession with light-sensitive materials. His series “Torsos,” (2005–08), for example, features images of cut and crumpled window screenings that he placed on chromogenic paper before exposing to light. The material’s capacity for light permeability incited Welling’s decision to experiment further. And what he achieved was an evocative miscellany of rich textures, which lend a sculptural quality to the work and highlight the essence of his process.

Working within this same paradigm, Farrah Karapetian and Matthew Brandt also approach photography with an enthusiasm for experimentation. Both studied under Welling, and his influence is apparent throughout their bodies of work.

Farrah Karapetian, Lateral Climb, 2015, Chromogenic photogram

40 x 30.25”, Unique, courtesy of the artist and Von Lintel Gallery

Karapetian bases much of her work in the physicality of her process. Her most recent series of photograms, “Relief” (2015), invokes the perilous plight of the refugee at sea, which she succinctly captured by illuminating the essence of the instant and its precarious nature by using less conventional materials as conduits for light, such as metal and plastic. Her experiments with ice, in particular, are largely responsible for lending an air of inadvertency to the series due to the transitory nature of this volatile element when placed on photosensitive at the time of exposure.

Mariah Robertson, 35, 2014, unique chemical treatment on RA-4 paper, © Mariah Robertson, courtesy M+B Gallery, Los Angeles

Brandt too, embraces the physical process of image making. His series “Lakes and Reservoirs” (2013–14) was a steppingstone in his exploration of image-making. By soaking colored photographs of lakes or reservoirs in the actual waters that each print represents, often for days and even weeks at a time, he didn’t just expedite a better understanding about the process of natural erosion but has since continued to incorporate the spontaneity of natural phenomena into his photo-making.

Like Welling, Liz Deschenes has done much to advance photography’s material potential. Since the early 1990s, she’s consistently worked with the medium’s fundamental components: paper, light and chemicals. Her photograms embody an ambience reflective of the atmosphere in which each is created. By exposing light-sensitive paper to either sun or moonlight, she creates variegated surfaces that reflect the unpredictability of atmospheric conditions, which are then compounded by the mutable impact of reactive chemicals. The results of her practice render mirror-like, monochromatic studies that don’t simply reveal the variant conditions under which each of Deschenes’ photograms are subjected, but their reflective quality invokes an immersive element that subtly urges viewers to ponder the nature of representation.

Walead Beshty has equally influenced the way we look at images today by calling attention to the conditions of his practice, which he leaves up to chance by choosing to work in complete darkness. The only conscious interventions he does make in the production of his vibrant and lush photograms involve a few basic logistics. These concern the size and scope of his works. Otherwise, the bulk of Beshty’s process involves an almost intuitive process of folding, crumpling and curling large sheets of photographic paper into various sections, which he then exposes to colored light sources while confined within an unlit darkroom.

Mariah Robertson, 38, 2014, unique chemical treatment on RA-4 paper, © Mariah Robertson, courtesy M+B Gallery, Los Angeles

Other practitioners whose exploratory approaches are helping to expand photography’s lexicon are Marco Breuer, Eileen Quinlan, Mariah Robertson and Alison Rossiter. Along with an appreciation for the unpredictable and often erratic interactions that result from the application of analog technologies, each of these artists aren’t only putting the physical nature of image-making at the forefront of their practice, they’re asking us to once again re-evaluate the way we read pictures. Unlike digital photography, which now enables total quality-control throughout what has become a highly regulated image-making process, this return to photography’s basic physics has brought with it a refreshing exuberance. Accidents and mistakes aren’t simply recognized as failures, but instead as original, one-of-a-kind works whose aesthetic value is largely determined by uncompromising external forces.