The Armory Show is 25 years old and bears little resemblance to the original Gramercy International Art Fair founded by New York Gallerists Colin de Land, Pat Hearn, Matthew Marks and Paul Morris. Held in the Gramercy Park Hotel the show was intimate, funky and fun. Artwork was placed willy-nilly throughout the hotel’s corridors and rooms, propped in tubs, hung on walls, laid out on beds. The show was a kind of happening, full of joy and spontaneity with the message that art was accessible and not too precious.

In the quarter century since the show’s inception the fair has grown into a behemoth presented in two giant covered shipping piers on the Hudson River. The fair became known as “The Armory Show” in 1999, when it moved to the 69th Regiment Armory, site of the famous 1913 Armory Show. It kept the name and the cachet of the original show when it moved west to the piers. Billed as “devoted to the most important artworks of the 20th and 21st centuries”, the fair is serious business, with business being the operative word.

Having made several circuits around the place (I left my Fitbit at home so can’t tell you how many steps I actually walked, but it was a lot), I’m here to tell you that “important” does not equal quality.

Ai Weiwei at Deitch Projects. The Armory Show 2019. Photograph by Teddy Wolff.

The work veers between the too slick and the too messy, mostly it’s just soulless. Some of the booths were so contrived and “arty” as to have been created by a set designer: Octavio Abundez at Curro, Guadalajara and Liliana Porter at Carrie Secrist Gallery, Chicago are two such examples, but there were plenty more.

There were lots of shiny things. Glitter, foil, mirror and sequins, twinkled from booth after booth subliminally telegraphing preciousness and expense. It’s clear that paying homage to an artist is so pre-21st century. Now, you just do what they did and call it a day. If people want a Joseph Cornell box and don’t have adequate coin, there’s a guy named Gary Brotmeyer, Laurence Miller Gallery, New York, who can fix one for you. Similarly, Candida Höfer at Sean Kelly, New York, appears to be taking not just a page, but the entire play book from Andreas Gursky. Don’t get me wrong, both of these artists are very good at what they do and probably excelled at art school, but technical know how’s really not the point, is it?

Then there are the scraps from the floor of the artist’s studio. They’re by the actual hand, but do you really want them? I guess somebody does because there were several Alex Katzes of dubious quality being proudly flogged.

Tim Noble and Sue Webster’s Instagrammable “Lucky” from 1999 seems particularly appropriate today. Initially the message was most likely ironic. Now, it can flash at you encouragingly from the rumpus room of your sliver-building aerie, providing a 24-hour/365-day affirmation. Your life may be shit, but you’ve got plenty of dough in the bank.

Eric Fischl “Edie and Paul.” Courtsey of Setareh Gallery

Eric Fischl is a really good painter whose work I admire. He is in and of himself one of those trophy artist that collectors salivate after. Being representational, his work is easy to grasp. Then there’s that Hamptons connection and his buddy-buddy relationship with names-you-would-know and the frisson of those sexually charged pieces he used to paint that still hovers over his career. With “Edie and Paul” (Setareh Gallery, Düsseldorf), you add big name celebrities like Edie Brickell and Paul Simon as subjects and you double the whammy. Possessing the painting elevates you into the big time suggesting an intimacy that confers a touch of that star power. It’s a pity because it ruins the painting for me. If it was two anonymous people, I’d like it so much better.

Installation view of “Star Ceiling” at The Armory Show. Photograph by Rich Lee, courtesy Pace Gallery.

Great fanfare accompanied Leo Villareal’s site-specific 75-foot long “ Star Ceiling”, a pretty transparent attempt to glom onto Yayoi Kusama’s colorful coattails. Artnet actually says it’s “guaranteed to be an Instagram sensation”. Is that what it’s all about these days? I was unimpressed having recently seen Katarina Löfström glorious “Fugue” from 2016. Her piece, which is simpler and so much more lyrical and poetic than the tech-heavy Villareal’s demonstrates not only the difference between a feminine and a masculine approach, but also how so often, less is sometimes so much more.

I’m not a complete party pooper. I did groove to Pascale Marthine Tayou’s monumental “Plastic Bags’ installed in one of the main intersections of Pier 94.

Lawrie Shabibi booth at The Armory Show. Photograph by Freddie L. Rankin II.

Over on Pier 90 I struck gold with British-Trinidadian artist, Zak Ové (Lawrie Shabibi, Dubai). Ové’s work has an authenticity that makes it both visually arresting and also powerfully evocative. Ové explores African identity and the African diaspora using collage and sculpture. His doily paintings, made from hundreds of colorful crocheted doilies (“Granny Psychedelia”, according to Ové), reference the rise from working class to genteel respectability, as well as, African and Afro-Caribbean masks which appear within the fractal-like explosions of wool and cotton. Masks also appear in Ové’s car-part sculptures. I loved the audacious attitude of his boom boxes, four of them arrayed on the wall. Skateboard P, a mannequin of a boy that Ové has painted and embellished with skateboard, animal skull and trinkets was strangely compelling with the quiet presence of Degas’ famous “Little Dancer Aged Fourteen”.

Eric Croe at Sorry We’re Closed.

Also, at Pier 90, Davidson, New York had some wonderful Torkwase Dysons: “Damn-Dam, Levy-Levees (Water Table)” and “In the Middle of the Ocean 9 (Water Table)” and Sam Messengers. Parisian Laundry from Montreal displayed the strange cartoons of Joseph Tisiga that meld Archie comic book characters with indigenous Canadian culture. I was delighted by Eric Croes’ fanciful ceramic totems at Sorry We’re Closed, Brussels.

At Pier 94, Halsey McKay, East Hampton, featured the intense little waste-landscapes of Matt Kenny. Patrick Jacobs’ oddly entrancing miniature dioramas “Swamp Nocturne” and “Pink Forest with Sickle Moon” were at Pierogi, Brooklyn. Peter Campus at Cristen Tierney, New York, is doing some interesting things with video and landscape breaking it down into ultra slo-mo animated pixilated blotches. There were some beautiful Jennifer Bartletts at Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York, as well as Jay Heikes “Mother Sky”. At Galleri Bo Bjerggaard, Copenhagen, Jules de Balincourt’s retro outsider, nocturnal beach scene held its own against the expressive works by Per Kirkeby. Mary Heilmann’s ceramic “Descending Squares #9” at Carolina Nitsch, New York was a refreshing splash of lemon.

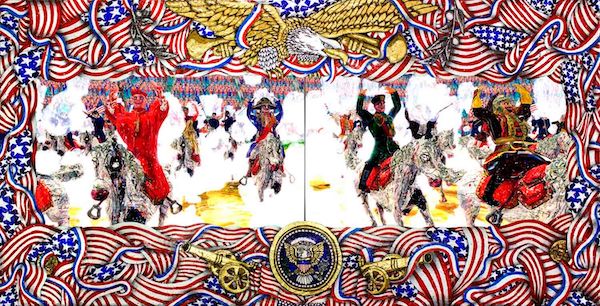

Frederico Solmi “Counterfeit Heros” at Ronald Feldman Gallery. Image courtesy Federico Solmi.

There was very little political art (one notable exception being Frederico Solmi’s “Counterfeit Heros”, which sets your teeth on edge with its manic display). I found this situation kind of unsettling. Here we are teetering on the brink of disaster and there seems to be a tacit agreement that we’re just not going to discuss it. I thought that was one of art’s central roles. But I guess silence and censorship is what happens when it becomes all about not pissing off clients who benefit from the status quo.

I get that it’s about selling art, but The Armory presents itself as such a primo aesthetic experience. Starting with the name which aligns it with the seminal art experience that was The Armory Show of 1913. As if! Granted, part of that early show’s impact was the fact the transformational work exhibited from Europe was a complete surprise. You’d never be able to (nor need to) produce such an earth-shattering event now because artists are so plugged in to each other.

But more to the point, the first Armory Show was artist- not dealer-driven. It was the initial project of the Association of American Painters and Sculptors (AAPS). The AAPS mission was lofty. Not only did they want to create expanded exhibition opportunities for young artists, they also wanted to provide educational art experiences for the American public. Given Saturday’s general timed admission fee of $57 for two hours, this “of the people, by the people, for the people” attitude is a quaint relic from a time when not every single thing was monetized up the wazoo.