Sandyland

It put me in a great mood (once I got past the shock of a $12(!) charge at the adjacent UCLA parking structure) going into Sandra Bernhard’s show at Royce Hall. Girls night out; (boys, too). Homecoming. Lots of anniversaries among that crowd over the last couple of years. Her show a couple years back at REDCAT had been a full-force smash on every level; and another show at Royce a couple years before that had been just as good. I loved the REDCAT stage; but it’s always good to be back in the big house. She had her longtime music director with her, Mitch Kaplan (though I thought Carla Patullo did a great job with her at REDCAT). So it was cozy and we knew things would go pretty smoothly. We were all ready to party in Sandyland.

The first number in Sandra’s shows are always key – always of a certain vintage, just slightly off the beaten track but rocking – ‘you’re not expecting it, but hey this is Sandra in her private space and she’s sharing it with you goddamnit’; vulnerable but fierce; and this one threw me off just a bit – Gordon Lightfoot’s “If You Could Read My Mind.” That’s going way back; maybe before some of you (Artillery readers) were born. Well okay, ya know – give the lady some space. Hmm… ‘the movie queen who gets burned in a three-way script…’ Well. From there, it was ‘let’s catch up, pals,’ and we were on to a family slide show (verbal thank you) with her partner, Sara, and daughter Cicely – who apparently had some wise advice for her Mum. “Edit.” I love travel tales; and there have been some fabulous destinations and detours for Sandy and the gang over the last couple of years – but do we have to hear about every ONE? This part of the show went on WAY too long. (I think she had to be aware of this, too, by the time she wrapped the segment.)

Now – can we just talk about the dress for a second? It was by a new-ish young design group called TONE. (Their Manhattan store is between 10th and the River.) No – I’m not going into fashion blog mode here – these are serious considerations for people like Bernhard – not just as a matter of personal style (though of course that’s important, too) – but as a theatrical performer. Anthracite jersey, deep V-neck, not quite on the bias, but body-skimming, over-the-knees, a bit loose (good for a rocking performance), and – with pockets – something I noticed immediately. At first I thought she had a hand poised just behind her hip; and as she pivoted, I saw that the hand was actually in a pocket. There’s a certain deliberation in this very loose sort of casualness. And she worked it: one hand in, both hands, pivoting, slouching, etc. Don’t get me wrong – I LOVE pockets in dresses. (Two of my own favorite black dresses have pockets.) But it just didn’t work. That was a disappointment – especially after the 2011 REDCAT show, where she rocked Ralph Rucci/Chado haute couture.

Then: more fun and adventures on and off the road; flashbacks to her Detroit/Arizona girlhood and family affairs, so to speak (she even did her own song co-written with Mitch about it – “Arizona”; not a success); the riffs on pop culture, advertising and mass merchandising; and finally the big closer (“Listen to Your Heart”) featuring Lili Haydn in a scorching rock violin cameo. She stayed on for the final cadenza – this one, not far back enough – “Wrecking Ball.” Well that broke a wall, alright. But it just wasn’t all right. Bernhard’s costume change was also rah-rah and definitely not right – something between a cheerleader get-up and tennis whites. (Memo to @SandraBernhard: contact @serenawilliams and/or her sister Venus.)

These things happen. That’s why we dance in front of mirrors. We figure out the moves. ‘You will dance again (was I talking to myself?),’ I thought to myself, driving back home down Sunset. ‘It will be all right….’ (I’m singing – silently – to myself, staring at the downtown lights.) Or maybe not.

The following Saturday (February 18th), I was once again making my west towards UCLA with a few stops along the way, including Richard Telles Fine Art on Beverly, where the brilliantly eccentric B. Wurtz was opening a show. I don’t mean that pejoratively in any sense. (Not that eccentricity needs any defense, especially here in America. If anything, we need far more of it.) I mean it literally, in that Wurtz’s work has always been a bit off-center (but never ‘off-hand’) in a way not unlike Richard Tuttle’s, but far more deliberative, almost meditative. There is an element of the Fluxus gesture here, the raw scrappiness of Arte Povera, but more considered, almost deliberately posed. The materials are not merely commonplace and everyday, but disposable – he frequently uses things like plastic shopping bags (maybe a bit less common from now on, given that they’re now banned in most California supermarkets), mesh fruit or potato sacks, plastic food containers and lids and plastic cups, paper plates, wire and string. Sometimes the wire is simply clothes-hanger wire; and in one of the pieces here, he uses an actual hanger that looks straight from the dry-cleaner’s.  But it makes perfect sense when you see it – an isosceles triangle in line beneath a similar triangle of wire (the topmost element from which the rest of the piece is suspended). A length of cloth hangs off the hanger like a banner, seemingly set off asymmetrically to one side, on which buttons are affixed in a subtle zig-zag array. Except that approaching a bit closer, we see that the banner (some portion of which was painted green) has been torn in half (though are we even sure of that), the oversize ‘button’ at the bottom is a green coffee-can lid. (There’s occasionally a slightly Westermann aspect to Wurtz’s work, as distinctive as it is; and you can see that here.) In another piece – a trio of plastic bags perched on slender wood dowels – one sees a bit of ‘zhoozhing’ going on – first, with the given element of color and pattern on the uppermost red-and-black checked bag and a subtle emphasis to its volume, projection and overall shape; and then in the two pale green plastic bags – their respective volumes offset in a kind of perpendicularity on their respective square wood bases, set just beneath the cruciform stepped planks and base. (Call it a red-and-black mass.) I think Wurtz’s antecedents go even further back – to Miro and Picabia. But these are unique and thoroughly American works, their magic and whimsicality held in place by a quasi-mathematical rigor.

But it makes perfect sense when you see it – an isosceles triangle in line beneath a similar triangle of wire (the topmost element from which the rest of the piece is suspended). A length of cloth hangs off the hanger like a banner, seemingly set off asymmetrically to one side, on which buttons are affixed in a subtle zig-zag array. Except that approaching a bit closer, we see that the banner (some portion of which was painted green) has been torn in half (though are we even sure of that), the oversize ‘button’ at the bottom is a green coffee-can lid. (There’s occasionally a slightly Westermann aspect to Wurtz’s work, as distinctive as it is; and you can see that here.) In another piece – a trio of plastic bags perched on slender wood dowels – one sees a bit of ‘zhoozhing’ going on – first, with the given element of color and pattern on the uppermost red-and-black checked bag and a subtle emphasis to its volume, projection and overall shape; and then in the two pale green plastic bags – their respective volumes offset in a kind of perpendicularity on their respective square wood bases, set just beneath the cruciform stepped planks and base. (Call it a red-and-black mass.) I think Wurtz’s antecedents go even further back – to Miro and Picabia. But these are unique and thoroughly American works, their magic and whimsicality held in place by a quasi-mathematical rigor.

Institutional Critique – and other exhausted therapies

And so four nights later (February 12th), I found myself in the same place – or just adjacent to it, in the Billy Wilder Theatre, listening to a panel discussion on “The Future of Institutional Critique.” As in – did it have one? I sometimes wonder why I torture myself with these gas-fests. But we have these questions; and there’s always the possibility that one of them will actually get answered – even if it’s not the same question that’s in your head.

And so four nights later (February 12th), I found myself in the same place – or just adjacent to it, in the Billy Wilder Theatre, listening to a panel discussion on “The Future of Institutional Critique.” As in – did it have one? I sometimes wonder why I torture myself with these gas-fests. But we have these questions; and there’s always the possibility that one of them will actually get answered – even if it’s not the same question that’s in your head.

The discussion – among the two curators, Anne Ellegood and Johanna Burton, and four of the artists, Judith Barry, Dara Birnbaum, Andrea Fraser and Mary Kelly – was already in progress when I arrived. The focus seemed to be on art historical appropriations and psychoanalytic aspects of various ‘critical interventions’ from the post-structuralist perspective that shaped many of the works or the thinking behind them. They used examples from their own work and slides of quasi-seminal pieces from the Hammer and other shows. The discussion seemed more digressive than discursive, eliding from one subject to the next. As soon as Louise Lawler’s name came up, I knew I was in for a rough time. But then so did Gretchen Bender’s, and it occurred to me that the discussion would inevitably pivot between various polarities and approaches (as Bender’s own work did), if it was to be at all coherent. (It also underscored another problem with the show’s density. Bender’s work (or some of it) is a show unto itself. You can’t just squeeze it in.)

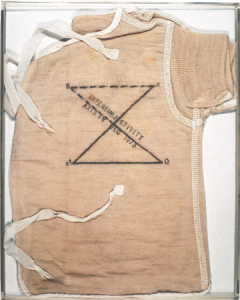

Moving from different approaches – developing a “different kind of quotation” – to the evolution of artistic practices. Mary Kelly’s “Post-Partum Document” came up opportunely. Okay, I think she brought it up herself; but if anyone was qualified to tease out the nexus between artistic practice and institutional critique, it’s Kelly, who has actually written thoughtfully on matters related to the topic if not directly on it. Of all the panelists, Kelly was by the far the most precise and deliberative, yet generous in accommodating the digressions of her co-panelists. (Too accommodating? I would say so.)

Not unlike Rirkrit Tiravanija, more than one of the panelists insisted that their art should in no way be construed as “social activism” – as if that would detract from its formal ‘specificity.’ Yet Kelly’s work (as well as that of several of her peers in the show) arguably engages both social and political spheres. The panelists’ reticence to embrace even their own ‘specific’ institutional critiques, much less larger institutions (e.g., patriarchy, the marketplace, the constellation of pathologies camouflaged and protected by entrenched social convention) again made me wonder what the hell I was torturing myself for. “Won’t commit…” “Won’t leave it behind….” At various points, you wondered if their current conception of institutional critique was simply a tarbaby they couldn’t quite let go of.

“All strategies get used up,” Judith Barry sighed. “I’m hoping for this regeneration through something….” “No one really embraces it. No one really claims it,” Andrea Fraser chimed in. “It kind of came and went at a certain moment…. But then it came back.”

Uh, sort of…. At moments the conversation seemed to see-saw more than just ebb and flow. Fraser seemed particularly self-contradictory. Mary Kelly tried to steer the conversation back to something resembling the “discursive site” of the best of this work. Aside from cueing the artists, the curators were mostly detached from the conversation. With Kelly and Barry, they seemed to want to reignite dormant synapses that might bridge ‘deconstructive strategies’ with ‘productive strategies.’ Dara Birnbaum wasn’t buying it. “I’m not as positive…. I find myself silent. I don’t know how to continue artistic practice.”

Uh, sort of…. At moments the conversation seemed to see-saw more than just ebb and flow. Fraser seemed particularly self-contradictory. Mary Kelly tried to steer the conversation back to something resembling the “discursive site” of the best of this work. Aside from cueing the artists, the curators were mostly detached from the conversation. With Kelly and Barry, they seemed to want to reignite dormant synapses that might bridge ‘deconstructive strategies’ with ‘productive strategies.’ Dara Birnbaum wasn’t buying it. “I’m not as positive…. I find myself silent. I don’t know how to continue artistic practice.”

Surprisingly, Andrea Fraser could relate: “I’m also pretty pessimistic. I’ve considered career changes … psychoanalytic training.” This actually made some sense to me. It also alarmed me slightly to picture Fraser in an analyst’s chair. (Note to self: Get Janet Malcolm on this if it ever happens.) “I’ve decided not to show work in the U.S.” I was too far away to see the expressions on the curators’ faces; but I had the impression of a vaguely WTF frisson rippling through the audience. She caught herself in the next moment or two. “Well, let’s say, Chelsea.” She was even starting to see her institutional practice as a “rear guard activity…; defense of a social and cultural space that is being lost.”

Between Fraser and the other panelists, there was a certain litigation, so to speak, of the declining ‘post-modern economy of affect.’ Fraser seemed particularly prone to juggling contradictory positions within a single paragraph. There was ‘no narrative.’ Building the narrative was crucial. There were ‘many’ narratives.

At various points, the conversation to seemed to diverge from more fundamental post-structuralist, post-psychoanalytic points and principles into more abstruse theoretical turns. (What that means for those of us whose grasp of Lacan and Derrida is less than secure in English, you don’t want to know.) When I looked at my Twitter feed later that evening, I saw that arts journalist Carolina Miranda had tweeted at one point (among many tweets), “This is getting super theoretical and psychoanalytical. #help” She wasn’t kidding.

The questions from the audience didn’t exactly throw any light into these dark vortices. It was a bit hard to hear them, and some of them were prefaced with long comments or idiotic compliments. After one such long comment/question, Anne Ellegood simply said, “Thank you.” Huh? It was something out of Kafka. I hurried home before I turned into a cockroach.

Take It or Leave It (or – we’ll always have Paris)

I was frankly a little apprehensive just going into Take It or Leave It (at the Hammer Museum). The title alone is a bit of a throw-down; and, given the recent track record on several of these large curated shows, both thematic and ‘invitational,’ just a bit risky; very much ‘showing her hand,’ I thought – the hand in question being Anne Ellegood’s. Setting to one side the 2012 Made In L.A. invitational, which you can’t really hang on her entirely, consider a title like, “All of This and Nothing.” What? As in the Psychedelic Furs song?? Frankly that’s all I could think of when I saw it. But seriously – it made a sort of sense, as you walked through that show. ‘A suit to wear on Mondays; a coat, a magazine…. A painting of the wall; a knife, a fork and memories; a light to see it all….’ (And timely, too – consider: “A bank that’s full of promises / A telephone that lies.” [I see I was a bit vague on the lyrics. Twenty-five years will do that. Note to self: ‘brush up your Shakespeare.’]

The last verse is another chilly winter breeze in retrospect:

Hmmm…. Don’t get me wrong. I think I understand Ellegood’s underlying approach here; and I’m sympathetic – at least philosophically: the uncertainty – a principle that’s been around for some time now, but that seems to resonate more fatefully with each footstep; sleek but complex superstructures that seem to disguise and distract from the decaying internal and under-structures; the contingency; the noise. Maybe you want to shake the viewer’s headset just a bit – or knock it off altogether. I get it.

Ellegood seems to have knocked around some of these ideas for a while. She made a splash with a show of sculpture she did for the Hirshhorn in Washington, D.C. (where she was posted before coming to the Hammer), The Uncertainty of Objects and Ideas. Regardless of what you came away with, it was a show, some felt, that needed to be seen (and heard) – itself something of a point to make in our permanently dysfunctional government town. But the ‘take-away’? That part was a little dubious. Ellegood’s agenda was ambiguous and ambitious in equal and daunting measure. E.g., among other things, “ … the beauty and horror of life.”

“And what does all this physically look like?” asked the Washington Post’s reviewer. “For the most part – and I mean this in the nicest possible way – a huge pile of crap.”

The review, it should be noted, was not uniformly negative. Also, Blake Gopnik had approving and affirmative comments to make on that show in the same publication’s pages.

Then there was Made In L.A. I – a stretch in every sense. Do you remember who won the Mohn Prize? Neither do I. (Okay so I looked it up – it was Meleko Mokgosi.) As I said, Ellegood was not a solo show-runner. There were three other curators and a separately impaneled jury for the Mohn Prize selection. (From the looks of the current roster which is just being released today, it looks like they’ve reined it in a bit.)

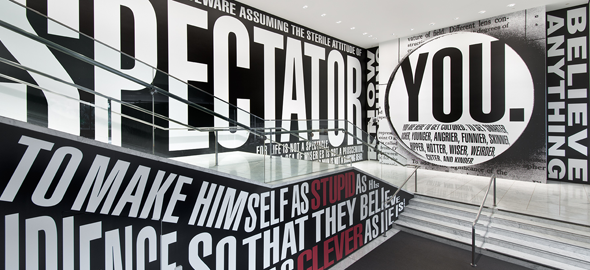

We felt a bit trepidatious just walking into the lobby, which was done up by Barbara Kruger – never louder or more hectoring than in this installation. Talk about ‘society of the spectacle’ – it felt like 12 Years A Slave, with ‘spectator’ substituted for ‘slave.’ “YOU are here to get cultured, to get smarter, richer, younger, funnier, skinnier, hipper, hotter….”; and apparently whipped into submission. “Don’t tell me how to look at something…,” Opera Buddy muttered on the way up the staircase. ‘No,’ I thought. ‘That is not why I am here; and it never has been.’ As far as ‘institutional critique’ went, I thought it was a lame way to start. Fortunately, there was liquor upstairs.

There were already throngs heading into the west galleries for Take It or Leave It, which seemed to account for a certain dimness on that side. So we finished our drinks and headed over to the east side for Tea and Morphine: Women in Paris, 1880 to 1914, a show curated by Cynthia Burlingham and Victoria Dailey from prints and drawings recently promised to the UCLA Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts by Elisabeth Dean, and the Grunwald’s existing holdings in that period. The Hammer always does fantastic brochures for its shows; and their publications department really outdid themselves for this one – with rich black-on-black Decadent-Nouveau poppy-paper – with gold superimposed quotation: “She wanted to die, but she also wanted to live in Paris.” (from Flaubert’s Madame Bovary) It’s just gorgeous – and so is the show. I’m not going to get into it right here, but it’s pretty great; and some of the prints and drawings in the show are simply unforgettable.

It was good to emerge from that dark so-called ‘Belle-Epoque’ Paris, where the vast majority of women were scarcely a social step removed from slavery. But it was already too late to hear music at Ace; and we moved on to “Take It.”

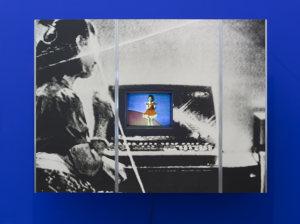

I almost don’t know how we did – and in fact, given the crowd, there was only so much we could take in. (A couple of the more iconic pieces – that sounds oxymoronic, but just go with me – were a bit lost amid the jumble.) It occurred to us that the galleries seemed a bit dimmer simply because of the density of the exhibition (to say nothing of the crowd). There were also semi-enclosed spaces for single and multi-channel video installations. But even the evolving ‘dialectic’ of some of these works seemed a bit lost in a cacophony of their own making, or in tandem with nearby art or installation work. E.g., did I actually see Dara Birnbaum’s “PM Magazine,” or am I confusing it with another video installation? You have some sense of where Judith Barry is going with her work, but the impact of the most recent work seems dissipated here, if not lost entirely.

I almost don’t know how we did – and in fact, given the crowd, there was only so much we could take in. (A couple of the more iconic pieces – that sounds oxymoronic, but just go with me – were a bit lost amid the jumble.) It occurred to us that the galleries seemed a bit dimmer simply because of the density of the exhibition (to say nothing of the crowd). There were also semi-enclosed spaces for single and multi-channel video installations. But even the evolving ‘dialectic’ of some of these works seemed a bit lost in a cacophony of their own making, or in tandem with nearby art or installation work. E.g., did I actually see Dara Birnbaum’s “PM Magazine,” or am I confusing it with another video installation? You have some sense of where Judith Barry is going with her work, but the impact of the most recent work seems dissipated here, if not lost entirely.

Working my way through the show, I breezed by Sue Williams’ “The Art World Can Suck My Proverbial Dick” and it scarcely registered, even though, by that time, I was more or less thinking the same thing. Some artists seemed to be treated almost as after-thoughts. I have a certain distance on Jenny Holzer – but give her work some space, goddamnit. Then there were the losers whose presence here was simply insulting. May I just say that I’m through with anyone whose purported work of ‘social engagement’ is in fact about social avoidance; whose notion of the ‘institutional critique is just sucking at the institutional tit – and yes, I mean you, Rirkrit Tiravanija. Give me a break. Makes me think of Paul McCarthy as a choirboy – which of course he is; and I’m getting tired of that, too. Speaking of McCarthy, I tend to think of Nayland Blake as his spiritual nephew. He’s here, and of course “Gorge” is in this show, but I didn’t see where it was. (Obviously, I didn’t necessarily linger at every video installation.) The Ginger Bread house is here, too; and you can’t miss it. It’s in the lobby – although it, too, was hard to take in amid the crowds milling around it. You may feel the need to take shelter there from the Kruger-rant on the walls going in or out. William Leavitt and Mike Kelley are here, too, but the placement of the Leavitts seemed almost indifferent; and the Kelley “Craft Morphology” sock puppets were wedged in too tightly. A serious mistake – again, a little space please!

A few pieces offer a bit of relief amid this obstacle course. The Gonzalez-Torres seemed almost a forlorn rebuke to the show, but its poignancy was not entirely lost. I’d like to look at the Mark Dion pieces (again? did I see them the first go-round?). There’s a Cady Noland and a Matt Mullican. The Fred Wilson Murano glass chandelier (“To Die Upon A Kiss”) would look great in and be oh-so-appropriate for my living room work space (where it’s so toxically cluttered you could actually ‘die upon a kiss’). I more or less ‘hit my wall’ – more specifically what looked like a chalkboard – covered in text identified as Valerie Solanas’s SCUM Manifesto. I didn’t bother to verify whether it actually was, although there were clusters of viewers inspecting this paragraph or that. Among all the appropriations this seemed the most egregious and insulting; a witless (to say nothing of exhausted) gesture, its failed irony just one more exhibit in the on-going debasement of language. For all of its shrieking hysteria, there’s probably more serious cultural and institutional critique in Solanas’s original manifesto than half the objects in the show.

I met up with Opera Buddy again in the foyer outside the gallery, gazing intently at a monitor playing Andrea Fraser’s “Official Welcome.” I watched as Fraser eddied around her podium in the video, eventually disrobing. “Are you done?” Opera Buddy asked. “I guess so … “ (There was another video installation in the room directly behind us.) “Are you?” Opera Buddy looked as me as if I was mad. “Yes!” We pushed open the door. “It was so obvious she couldn’t wait to get her clothes off.” Opera Buddy’s understanding of performance is deep.

We weren’t the only ones in a hurry to get out. Masses of people were streaming from the galleries and over to the other side of the building. If there were such a thing as culture tennis, the scoreboard at the Hammer that night would have read 30-(Not)Love. Absent the love, you opt for a stimulant or narcotic – even if it has to be taken in a Parisian hellhole.

awol – and into the cultural wild

I’m always a little skittish about openings. So much pressure – the drive – or just getting there; what to wear; running into someone you’ve been avoiding; the ‘keeping-up’ posturing – have I seen all the must-see shows, must-see films, read the must-read books? Have I kept up with the latest theoretical turn in whatever the critical vogue of the last several months is. (Something to consider with respect to the evening in question. A quick flip through Artforum, Afterall, or – dare I say it? – Artillery is always helpful.) I want to give up before I even get there – ‘oh doll, I’ve just been in bed drinking gin and chamomile tea, reading Flaubert and the latest Donna Tartt.’ (Will that at least cover the must-reading?) And it’s almost always the same people. Someone is always taking a picture just as you’re losing an eyelash or something – ‘Darling, it’s my half-Nevelson. Now for half a pipe – did you bring some yerba?’

For that matter, I can get dodgy about press previews – the earnestness; the emphasis on an artist’s process; the motives, impulses, strategies. (Doesn’t the work ‘speak’ sufficiently for itself?) There are exceptions to this; and once in a while, a little background is very helpful, even necessary.

And there’s so much happening on any given evening in L.A. – as there was on the evening of February 8th. There were at least two other events I’d already blown off. You know how it is – we get to them when we can. I was far more preoccupied with a chamber recital at Ace Gallery – Beverly Hills. A Bartok quartet and one of the Beethoven Razumovsky quartets were on the Emerson Quartet program and I was dying to go. But it was a double-wide party at the Hammer – two ‘must-see’ shows that had already opened; and Opera Buddy was keen on seeing at least one of them.