For Taiwanese artists Chun-yi Chang and Yinling Hsu—currently in residence at the International Studio and Curatorial Program for emerging to mid-career artists in New York—probing notions of temporality and human disconnectedness form the core of their practices. Less concerned with the specificity of their cultural identity, their work as members of a vibrant international community of artists takes on larger philosophical issues.

Chang explores insightfully the elusive nature of time with its two sides of eternity and impermanence. In Fairy Tale (2014), multiple video screens play continuous loops of images taken in and around the Mare aux Fées, a small body of water in France’s forest of Fontainebleau. In one screen as the water reflects the still verdant landscape around it, its wavering surface dispels any illusions of permanence of the fecund surroundings. In another two-part video, a little girl plays hide-and-seek with her friends in the forest. By juxtaposing frozen images of the child surrounded by the swaying trees and vice versa, Chang’s technique attempts to include a transcription of a character from her native Mandarin that translates as both form and phenomena. The mesmerizing lake, and the child’s garbled recitation of numbers before she looks for her quarry become signifiers of the binary nature of time that connotes the permanence of form and the phenomena of constant change.

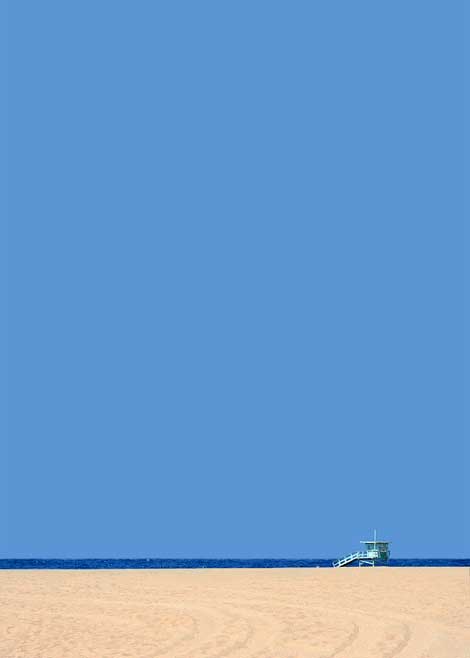

Similarly, in a series of small minimalist paintings titled “Sky Blue #1” (2014), Chang depicts the changing contours of a beach, the ocean, and the horizon with three horizontal strips of color as she walks along the waterfront. This static presentation of time is contrasted with an accompanying video that records time on the same beach through the ebb and flow of the water and the subtle changes in the tide with each passing wave.

For Hsu in her series “all happy returns” (2014), the irony of the title becomes clear in a group of figurative oil paintings that portray the plight of a so-called “taxidermist,” who can only relate to the spirit of a human body once it has been dissected and preserved. Afflicted by an extreme form of the 21st-century malaise of disconnectedness, the taxidermist finds solace in the company of animals, especially dogs that serve as his companions. The paintings tap a deeper sense of anxiety about impersonal relationships in Taipei and other major metropolises, the related behavior patterns, and the gradual destruction of meaningful human bonds.

Inspired by their personal circumstances, both artists investigate larger themes pertaining to the human condition. When pushed to locate herself from a cultural perspective, Chang revealed that her choice of medium and the focus of her work on time, change, and flux is linked with her evolving sense of self as an expatriate living and working in France. And for Hsu, her stultifying experience in Taiwan has led to the unraveling of a world that combines fact and fiction, fantasy and reality as she finds her true voice and form.