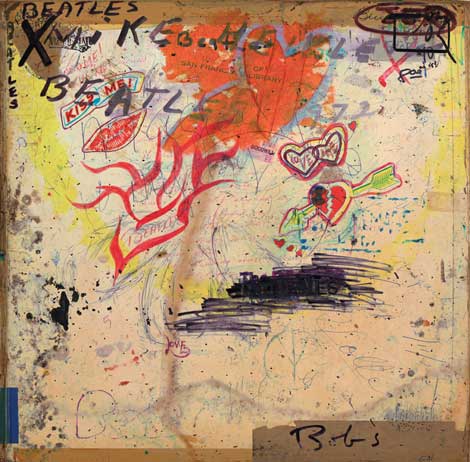

Lars Jan’s staging of The White Album has returned to Los Angeles; and suddenly I feel drawn back to 1969, a year that was in a sense my first real introduction to Los Angeles as three things simultaneously: a place (its suburban and studio/dream factory aspects clear...