The art world has been revisiting issues of identity and identity politics in recent months (see, e.g., the current issue of ArtForum), which had their own ‘second wave’ in the late 20th century borne largely upon the convergence of conceptualism, especially in its...

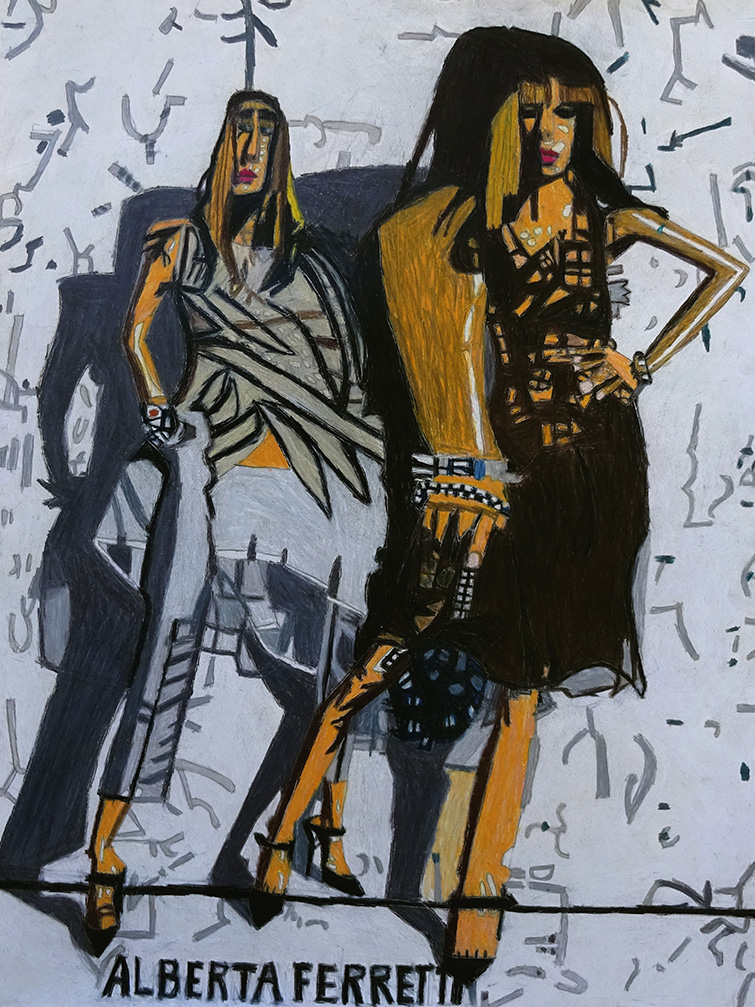

Strike the Pose: Getting high inside high fashion from way outside – the art of Helen Rae

read more