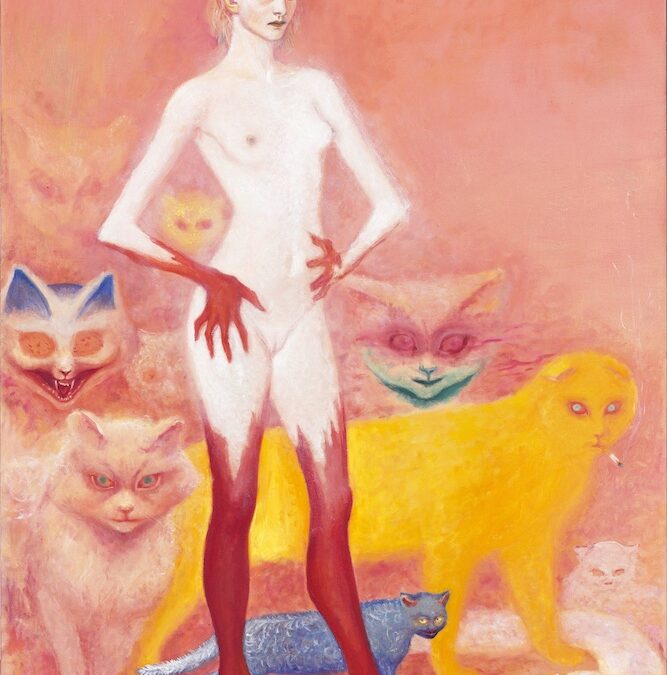

I felt dizzy at mosie romney’s show “every Spiral has its law” at Sebastian Gladstone. I could chalk it up to external factors (fatigue, harsh gallery lighting), but I suspect that the work itself was the incubator of disorientation. My previous visits to the space,...