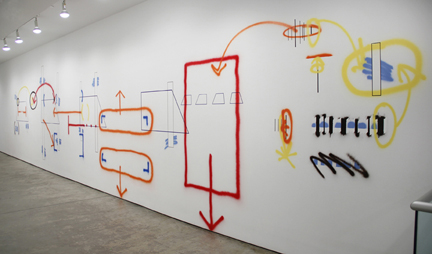

Having redirected his energies over the course of 20 years, from cast-resin sculpture to wall-based works combining painting with steel cables and short lengths of pipe, Peter Soriano has lately dispensed with objects, working on the wall in spray paint and acrylic...

Peter Soriano

read more