Your cart is currently empty!

Tag: sexuality

-

ASK BABS

Nonna’s No-NoDear Babs, I recently acquired an old painting of mine from grad school. It looks fabulous in the kitchen. It’s from a series of feminist art, large paintings of nude women in pin-up “cheesecake” positions taken from ’60s playing cards. I now have two grandchildren that are too young to really notice, but should I start to think about censoring my art around them?

—Considering Censorship in LA

Dear Considering Censorship, Those kids have one cool grandma! I say hang your painting with pride. It’s your house, and you decide what goes on your walls. Using this situation to give the little tykes an age-appropriate lesson in feminist art and critical thinking is actually being a responsible grandparent.

Kids are smarter than we think; they pick up on our slightest reactions, especially when it comes to what is and is not “acceptable.” If you don’t make the painting a big deal they won’t either. Sure, when the kiddos get older they might giggle or ask questions, but that’s to be expected. You have many years to consider how you will respond to their reactions to your work.

Obviously, you need to prepare for these discussions in collaboration with the kids’ parent(s), and I assume they are smart enough to want to raise kids who aren’t afraid or ashamed of sex and sexuality. As long as you’re all willing to talk to the kids in a matter-of-fact way that doesn’t make the painting taboo, they won’t fixate on it as an “off limits” object to obsess on; it’ll be “art,” just like everything else on your walls. If you need help steering the conversation in the right direction check out The Art Institute of Chicago’s Body Language: How To Talk To Students About Nudity In Art and the indispensable Guerrilla Girls’ Bedside Companion to the History of Western Art (which you probably already own).

Growing up surrounded by challenging art never made someone a troubled adult; growing up surrounded by adults obsessed with censoring challenging art does. Keep the painting on your wall and make your grandkids want to inherit it someday.

-

Ghada Amer

“Rainbow Girls” at Cheim & Read continues Ghada Amer’s inventive strategy of using thread as paint, and needle as paintbrush, but with a marked difference. Bold embroidered stenciled text covers her canvas. Women’s rights and Amer’s stance are as forthright as her effective use of language, which becomes a physical entity with weight and force.

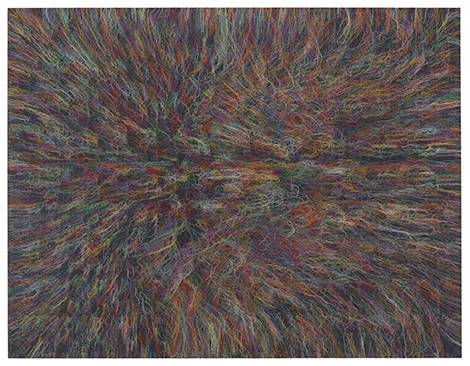

Ghada Amer “SUNSET WITH WORDS – RFGA”, 2013. Courtesy Cheim & Read, New York. Since her mid-career solo exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum in 2008, Amer’s highly personal exploration of femininity and meditation on the private nature of ecstasy have been at the forefront of her work. Shrouded through her signature use of colorful thread that both outlines her explicit images of women and shields them from immediate visibility, The Big Black Bang (2012), like many of her works, is inspired by The Encyclopedia of Pleasure, written by a 13th-century Muslim poet who openly discussed female sexual bonding. Set against a stark black background, rushes of windblown rainbows, like nature gone awry, reveal women seeking pleasure beneath the outward aura of indeterminacy. The complexity below the loosely threaded surface, and the play between visibility and invisibility gets taken to a different plane in these text-based works.

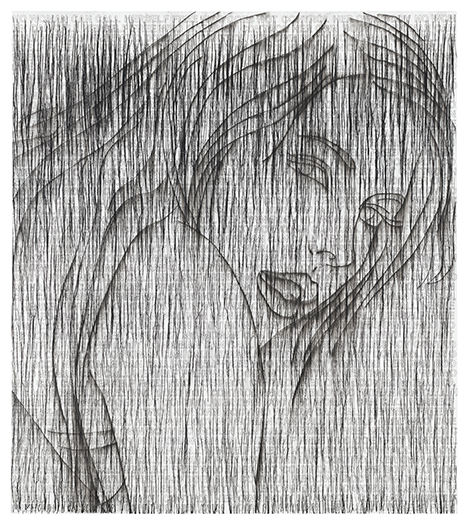

Ghada Amer, “THE BIG BLACK BANG – RFGA”, 2013. Courtesy Cheim & Read, New York. The quote “No woman can call herself free who does not control her own body,” adorns the background of Norah (2014). In the foreground a black, sultry embroidered silhouette stares out of the canvas. Resembling a smudged charcoal comic strip figure, Norah’s form is backlit by the recurring line from the birth control activist Margaret Sanger of the 1920s. Stripped from its original context, Sanger’s words still convey the collective voice of subjectivity while registering the denial and relentless silencing of that same voice.

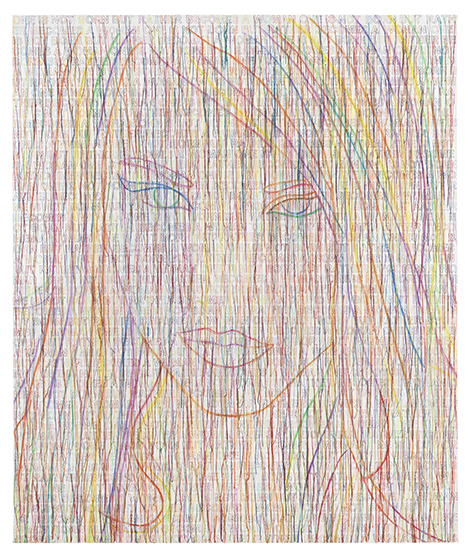

Aphorisms such as “One is not born but becomes a woman,” taken from the French feminist writer Simone de Beauvoir, shower Rainbow Girl (2013). Reminiscent of trailblazers like Jenny Holzer and Tracy Emin, whose art-texts were more personal and not always about women’s issues, Amer’s concerns follow in the vein of the African-American artist Glen Ligon. By commingling her embroidered female shadows with barely legible, repeated text, Amer highlights the plight of marginalized women, both from her own Middle Eastern background and a global context. Here, what verges on illegibility results in a series of dialogues between visibility and erasure.

Ghada Amer, “THE RAINBOW GIRL”, 2014. Courtesy Cheim & Read, New York. Amer’s embroidered declarations refrain from being didactic, yet echo the horror of women perceived as sexual objects. The power of the stenciled text is particularly potent, especially from the context of Middle Eastern calligraphy used by artists such as the photographer Lalla Essaydi in her work. In Mandy (2013), the stenciled text “I see my body as an instrument rather than an ornament” transforms the personal and diaristic into the political and public. In Amer’s works the formal appearance of the stencil has a supercharged affect.

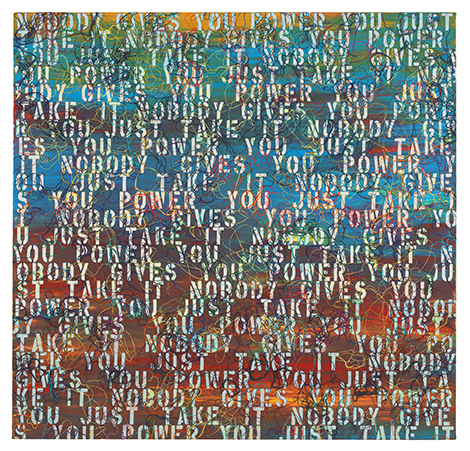

In the end, Amer’s pluralism not only addresses women’s sexuality through figuration, text-based works and sculpture, her art also embraces the comedian Roseanne Barr’s truism, highlighted in Sunset with Words (2013)—“Nobody gives you power you just take it.”

Ghada Amer, “MANDY”, 2013. Courtesy Cheim & Read, New York.