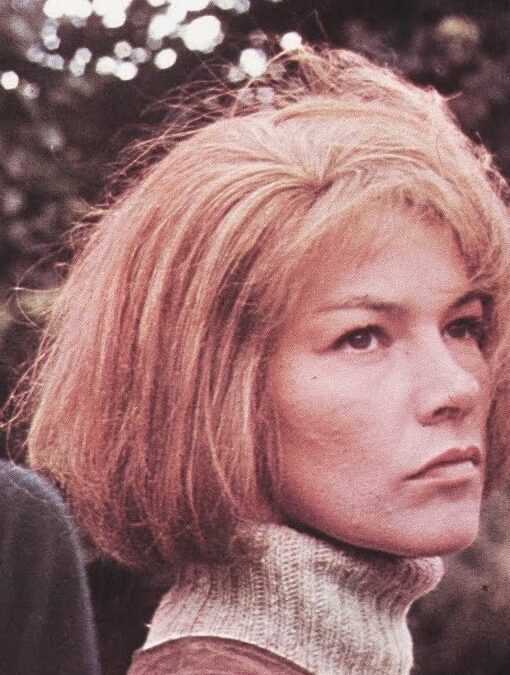

It is one of the great regrets of my life to have never seen Glenda Jackson perform live on stage—and there was at least one serious opportunity that somehow (almost inexplicably) passed me by—in a play I loved, directed by the playwright himself. The play was Edward...

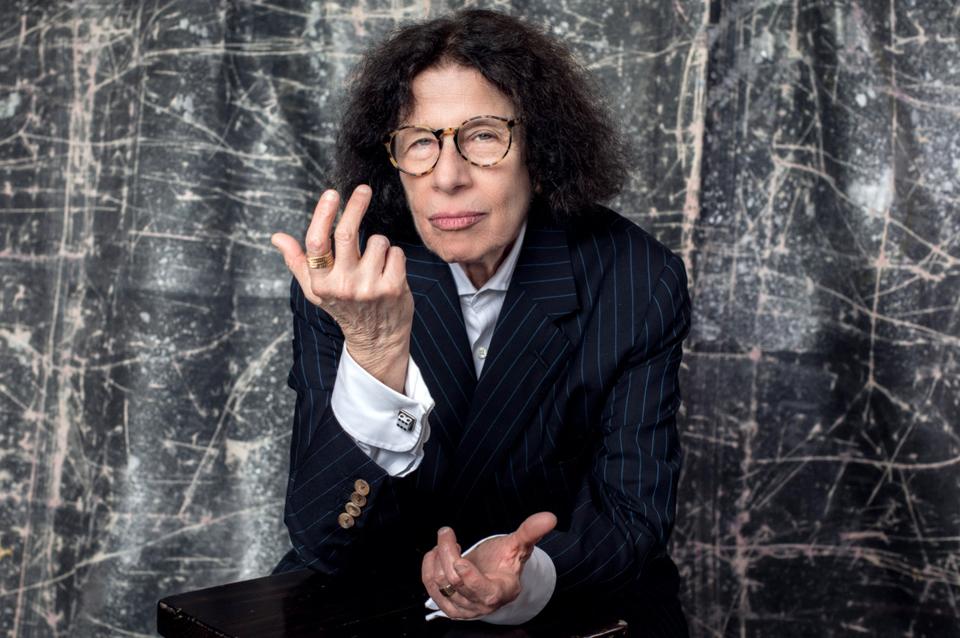

Glenda Jackson (1936-2023) Revealing Character and Defining a Moment

read more