Your cart is currently empty!

Tag: Landscape Photography

-

Local Color at OCMA

The subtitle “Works from the Orange County Museum of Art” made it clear that the exhibition on view there January 11 through March 9 was a collection show. But the main title, “California Landscape into Abstraction,” at first seemed an awkward and obscure attempt to tell you what the show was about. Before you were half way through, however, the exhibition’s visualization of its theme had taken over and was making marvelously clear what the title’s verbalization had not.

The show began in the museum’s lobby and continued through 10 galleries inside. By the time you got to the fourth one, what remained fuzzy in the title and texts was coming into sharp focus on the walls. In that gallery, for instance, what at first seemed an improbable juxtaposition caught your eye. The image commanding the room was Richard Diebenkorn’s Ocean Park #36, from 1970, a post-abstract expressionist canvas nearly 8 x 7-foot that is among the finest paintings in OCMA’s collection. Painted early in the 18-year period when Diebenkorn had moved from Northern California to Santa Monica, it’s a prime example of the series that gave it its title. The incongruity attracting your attention was that on the adjacent wall was a California seascape—Pale Moonlight, a painting done by Frank Cuprien in 1943 on a piece of masonite the size of a sheet of typing paper—that seemed almost insignificant by comparison to Diebenkorn’s abstract masterpiece.

The exhibition catalog describes Cuprien as a “debatable figure [who] managed to bridge the divide between genuine impressionist impulses and savvy self-marketing.” Even that seems an over-estimation, for by 1943 how genuine could impressionist impulses be? According to exhibition curator Dan Cameron, Laguna Beach, in whose 1920s art scene Cuprien became a leading figure, was “far enough from Los Angeles” to be “a haven for California impressionists.” Cuprien was as far behind the times as Diebenkorn was ahead of them. Still…there was a provocative resonance between the Cuprien and the Diebenkorn. The flickering band of “pale moonlight” in the former’s painting spoke to the vertical strip of hard-edged yellow at the center of latter’s canvas. The wanness of Cuprien’s gesture suggested that it has a remote but real relationship to the bold composition by Diebenkorn, whose view of the Southern California light and landscape outside the window of his Santa Monica studio almost certainly affected his painting, even if not as literally as that view of the sea affected Cuprien’s.

Richard Diebenkorn,Ocean Park #36, 1970, Collection OCMA, Gift of David Steinmetz The juxtaposition of Cuprien and Diebenkorn exemplifies the way that the installation of the art kept returning you to OCMA’s home ground in Orange County. The exhibition contextualized art in the collection that is universal in its significance as art that remains, for all that, regional. Another example of the exhibition’s strategy was in the second to last gallery, where an Anthony Hernandez photograph on one wall faced a photograph by Dorothea Lange on the opposite wall, and on the wall connecting those two was an “original sketch” over three-and-a-half-feet long for a public art piece by the late SoCal muralist Terry Schoonhoven.

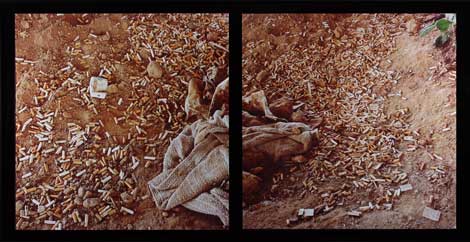

The Schoonhoven work is an example of what the catalog calls his vision “of local nature dramatized within unexpected formats and locations”—in this case, the darkened, seemingly abandoned interior of a bookstore whose plate-glass windows and double doors are silted up by the moonlit desert landscape outside. The Hernandez to the right of this image, Landscapes for the Homeless #24, (2003/04) looks straight down at a patch of desert littered with cigarette butts and other refuse. More than twice the width of the Schoonhoven, this chromogenic color print was framed in a way that divided it in half, as if it were two square images pushed together.

Anthony Hernandez, Landscapes for the Homeless #24, 2003-2004, Collection OCMA, Museum purchase with funds provided through prior gift of Lois Outerbridge Between the subject matter and the effect of the frame, the Hernandez looked like a blow-up of Schoonhoven’s double doors embedded in sand, and the Lange photograph on the other side, A Very Blue Eagle: Tranquility Vicinity, Fresno County, (1936) also had a formal relationship to the Schoonhoven. A dead eagle strung up on a barbed wire fence, its outstretched wings spread across the frame in a way that resonated with the wavering line of the desert sand piled against Schoonhoven’s plate glass. Though it went farther afield, to Fresno, this run of images sharing a dark mood gave visual life to the hyperbole “Paradise Endangered” that was the title on the gallery’s introductory text panel.

The fact is that the exhibition contained more photography, by far, than work in any other medium, and the photographs were often the visual glue that held the work in a gallery together. The overture to the exhibition in the lobby area culminated in Penelope Umbrico’s sensational Sunset Portraits on Flickr, (2013) which was a grid, in this installation, of around 1,300 snapshots lifted off the Internet. And the exhibition’s finale, in Gallery 10—the gallery after the one in which the Schoonhoven was bracketed by the Hernandez and Lange photographs—was a group of 29 photographs drawn from a single body of work by one photographer, Louis Baltz’s 1974 New Industrial Parks near Irvine, California. This was the series representing Baltz in the 1975 exhibition “New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape” that shifted attention in landscape photography in general from the earlier Northern California vision of Ansel Adams and Edward Weston (both of whom are also in the OCMA exhibition) to the SoCal landscape in Orange County.

Dorothea Lange, A Very Blue Eagle: Tranquility Vicinity, Fresno County, 1936, Collection OCMA, Museum purchase The predominance of photography was what first piqued my curiosity about the exhibition, because I was for many years a photography curator and have also served as the director of the California Museum of Photography at UC Riverside. Because photography exhibitions often contain well over 100 works, a curator of that medium feels especially the need to help viewers see how a visual theme can connect one image to another, in order keep the visitor to the exhibition from being overwhelmed by the sheer mass of material.

This is a knack that Cameron, faced with a checklist of more than 120 objects by 89 artists, applied across all the media in his installation, including and especially the photography. The approach served him well, giving an important collection that’s hard to sum up in verbal terms the kind of visual coherence that is what an effective exhibition always needs anyway. By the time you emerged from the exhibition, you did understand how the landscape art of earlier generations fed into the abstract art of a later one. The exhibition achieved this by being autochthonous, grounding the exhibition in the collection from which it came, and in its sense of the place where the collection resides.

-

Robbert Flick: “Freeways,” at Rose Gallery

When I was just out of school and began my first regular daily commute of the Southern California freeways, I remember stealing glances to either side of the road. I caught brief glimpses of the fleeting vistas, noting how with every quarter mile, my vantage point changed. On an extended road trip up through the Northwest and across the northern plains, I began taking pictures from the car. After a brief sojourn in the Midwest, I swept through the Southwest on my way back to Southern California, again, taking photos from my moving vehicle. I was never systematic about it; I simply shot things that caught my attention. When I returned to California, I bought an auto-winder for my already obsolete manual SLR so I could shoot faster. I was enchanted with the shapes of the surrounding hills and the trails carved by cattle into the hollows and steep inclines of Brea Canyon. I fantasized about putting an image of an open road, based on a photo I had taken in rural Washington, up on a billboard next to the 210 Freeway near Irwindale. I imagined that frustrated drivers would see it as they crept through rush hour. They would be either irritated by the unattainable simplicity of it or enter it visually as a meditative release to the dulling grind of traffic. Yet, as enamored as I was with the visual experience of movement—the changing curve of an overpass, the interaction of geometric shapes between the ramps and arcs of freeway interchanges, the mountains ringing the Los Angeles basin and the union of sky, soil and concrete—I continued to think of my perceptions as isolated moments that could be conveyed in terms of singular iconic images.

Robbert Flick, P2810809-823, 2011-2013 In hindsight, it doesn’t seem like much of a leap: abandoning the search for the singular image in favor of a sequential visual experience. After all, it is just an arrested version of what we see in films: the repeating frame. Robbert Flick made the leap after completing his “Arena” series (1977–1979) depicting a parking garage in formal black-and-white stills. His subsequent work conveys a fragmented sense of moving through Los Angeles in contact sheet-like photographs.

“Freeways,” Flick’s solo show currently at Rose Gallery through April 12, provided the setting for a conversation this past Sunday, March 30, between the veteran LA artist and his interlocutor, author and Los Angeles Times book critic, David Ulin. The Los Angeles Review of Books, which celebrates its three-year anniversary on April 19, put on the event as a part of the publication’s ongoing series of conversations between artists and critics. Introducing Flick, Ulin referenced their mutual interest in making an “art of the mundane” in a city where “daily activities like going to work tend to be overlooked in favor of mythic tropes,” adding that Flick’s interest in repetition or “retinal increments” resonates with the way that most people experience the city.

Flick’s freeway photographs, generated from thousands of still images the artist took during his commute from his home in Claremont to USC where he is on the faculty, cover much of the same territory I drove on my way to Bergamot Station to hear Ulin and Flick’s dialogue.

LARB event The freeway generates its own rhythm. It is far too easy to drift into a semi-trance-like state, realizing after a few miles that one has been driving by autopilot. This lack of focus, or, rather, focus on the destination while losing site of the journey, was indirectly the subject of discussion. Flick repeatedly underscored his interest in drawing attention to what is between the frames, and to “empathically respond to whatever is there.” He waxed poetic at times, describing how his morning walks provide unexpected sensual experience—taking in the aroma of someone’s shampoo from an open window, for example—that he would never notice if he were focused on a preconceived outcome.

Significantly, in titling his work with a series of numbers, suggesting a cool, rational nomenclature rather than a poetic, symbolic or narrative name, Flick signals a matter-of-fact empiricism. Visually, the cool nature of the observer comes through in the data-rich images. Yet, Flick’s work becomes ambidextrous at this point. His interest in observing experiences of the city that are regularly overlooked or elided seems consistent and at the same time at odds with his process. Whereas his collection of massive amounts of data and apprehension of the city through sensual experience speaks to an empirical evaluation of the city, Flick’s interest in responding empathically moves his practice into the realm of the subject and an interior world that coexists with that of the critical observer.

Robbert Flick, P2730297-352, 2011-2013 Ulin and Flick overemphasized the randomness of image collection in Flick’s practice, for he is very intentional about where he operates his camera and the rational for sites. He is also intentional when it comes to selecting which still frames, out of thousands, coalesce into a discernible narrative. And this is where subjectivity further enters the process. It is not a random selection process, nor is it statistically based, but it is predicated on Flick’s sensitivity as a photographer and an artist. As Flick stated in conversation, his photographs are fictitious. Flick compared the process of making his photographs to the process of writing and editing repeatedly, to arrive at a final narrative in much the same way Dylan Thomas wrote 30 possible word choices to end up with one.

Flick’s interest in investigating the minutiae of the city and creating a visual equivalent to sensual experience, whether it is the bounce of the train at a predictable location or reflected light illuminating the freeway—all stimuli Flick mentioned in his discussion of working and experiencing the city—does not result in a sequence of random images, nor is that the way we perceive our experience. It accounts for a certain amount of randomness, but the reality is that Flick is creating an authorial narrative.

ALL IMAGES COURTESY ROSE GALLERY

ROBBERT FLICK IMAGES: Archival Pigment Print, Signed in ink by the artists on signature label adhered to mount verso, Number one in a limited edition of five, From the collection of the artist

Robbert Flick: “Freeways” at RoseGallery. Ends April 12, 2014

At Bergamot Station Arts Center; for info: rosegallery.net -

Miles Coolidge

The photographs by Miles Coolidge recently on display at ACME, Los Angeles, are magnificently beautiful examples of the photographer’s craft. Simply as aesthetic objects, the photos are compelling: composed according to simple underlying geometries, they nonetheless display an inexhaustible wealth of infinitesimal detail.

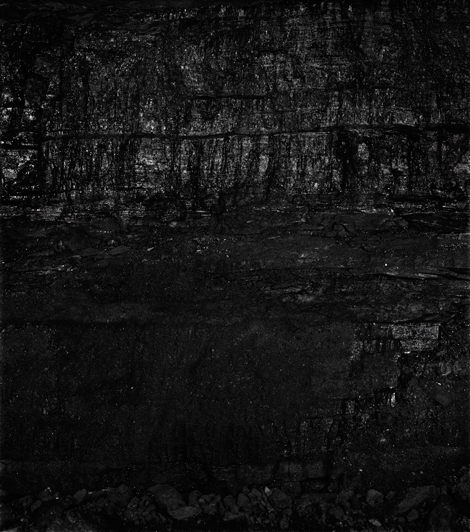

Aside from two recent examples of the ongoing series of UC construction mock-ups, the work in the current show includes a single monumental mural and four sizable black-and-white prints that make up a sequence: Coal Seam, Bergwerk Prosper-Haniel. Shot with an 8 x 10 view camera in a single day-long session, the four prints comprise studies of an “active working face” (the actual exposure of the coal seam) in a Ruhr Valley mine. Approaching the work is curiously like a descent into the mineshaft. The images at first are inscrutable abstractions. Then, suddenly, a narrow foreground space appears, strewn with rubble that abuts the vertical face of the seam, where work lights play over an extraordinary geography, every little rise and fall, crack and fault picked out to evoke a ghostly otherworldly terrain. About 75% of the way up from the bottom, each print shows a deep crack in the face of the seam, a pitch black horizontal mark that ties all the images together, and cuts each image with a crooked axis that suggests the lateral extension of the mine’s geography into a potentially limitless darkness.

Miles Coolidge, Coal Seam, Bergwerk Prosper-Haniel 3, 2013. Courtesy of the artist and ACME., Los Angeles. Formally and geologically rich, Miles Coolidge’s Bergwerk Prosper-Hamiel series is deeply embedded in the complex history of mining technology, German industrialization, and more general history of attempts to understand, control and exploit the environment. It also resonates with the history of photography at its very point of origin: the oldest surviving “photograph,” produced by Joseph Niépce in 1826/27, employed a bitumen-coated plate—while, thanks to the brilliance of German analytical chemistry, the off-the-shelf Epson inks used to print the current series employ pigments likewise derived from coal.

Miles Coolidge, Francis Gate, 2010-2013. Courtesy of the artist and ACME., Los Angeles. Although comprising only a single colossal 92 x 221 inch image, Francis Gate (2010-2013) is another examination of man’s impact on the environment over time. We see spread out as though along the course of a slow cinematic pan, a one-year buildup of debris at the Francis Gate sluice, constructed in 1850 to facilitate control of the Merrimack River and the development of the textile industry in Lowell, Massachusetts. As the eye moves diagonally across the gigantic print, an uninflected jet black ground is increasingly displaced by a chaotic welter of form and color—primarily green and grayish-brown from a distance; the closer one gets, the more complex becomes the play of color accents, as the captured objects (natural and human detritus) are seen in ever-increasing, perhaps incrementally infinite detail.

In all, this is an extraordinary show, where images of profound beauty are used to ground an artist’s photographic practice in a rich if unexpected matrix. Theory, chemistry, industrial, artistic and social history all come together to illuminate the marks that we make both on and under the land.

-

Adam Katseff

Throughout our evolution we’ve been afraid of the dark. As creatures primarily endowed with encephalic gifts, we aren’t well-equipped to vie with nocturnal animals, full of tooth and claw and with more finely attuned senses. They make quick work of us when we don’t see them coming. Darkness holds for us a sense of foreboding; in the dark we deliberately slow our breathing to hear what in the world is happening around us. Even in our aggressive modes: hunting and exploring, we quiet ourselves in the dark, peer into mystery, trying to make out the meaningful forms on the horizon.

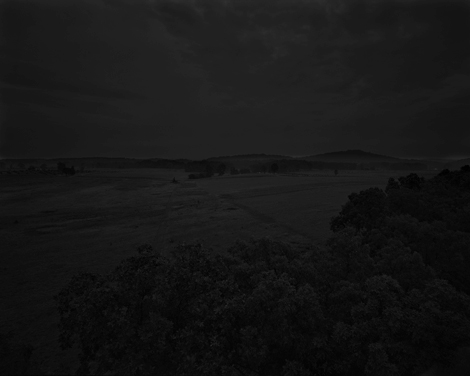

Adam Katseff’s work, “In the Course of Time,” at Sasha Wolf Gallery stands out from the crop of contemporary photography in New York galleries by presenting staggeringly beautiful nocturnal landscapes of lacquered shadow that are unironically mysterious. Method and content come together to make them so. A meditative, patient eye is required to gather these images—Katseff sets up his camera at night with the shutter wide open so the film can siphon up errant light from the moon and stars, before the dawn intervenes. The images require a meditative approach to perceive them as well. Shapes are initially hard to decipher. One’s eyes adjust and then lakes appear, made into smoky seamless marble, valleys morph into passages to the underworld, and snow-capped trees become circumspect honor guards (the “Night Landscapes” series, 2012-13). Katseff’s work is well and truly liminal: astride the border between the now and the ancient, the visible and the clandestine, the pedestrian and the mythic. We become acquainted with the night, looking at these landscapes. We learn patience, waiting for the Fairie to appear.

Adam Katseff, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, 2012. © Adam Katseff, courtesy of Sasha Wolf Gallery. The works in the “Flames” series (2010) aestheticize another of the primeval elements, in addition to earth and water. In these images fire appears to pour itself over the object, inhabit it, ravage it rather than simply consume it. Though these photographs are not as mesmerizing as the landscapes, they may make a viewer want to discount scientific accounts of fire as excitation of molecules in favor of more animistic explanations—possession, for example. The “Whole Night” series (2011) on the other hand demystifies the night sky, making it a kind of clever designer-wallpaper with stars leaving lighter traces of their passage in a graphic rather than organic style.

Katseff’s use of a black-and-white palette makes him very much a part of the history of fine art landscape photography following those like Edward Weston, Minor White and Ansel Adams. The attention to formal qualities is made more evident in his “Interiors” series (2012-13) where Katseff shows us model homes that are the opposite of the dark we left: simplified, defoliated, flooded with light, so that no corner allows for hiding. All is visible and known. But where Katseff’s work is most compelling is in its sense of not knowing what is up ahead, therefore causing us to scout the landscape with our senses on guard, fully alert.

-

Kim Stringfellow

Kim Stringfellow’s photographs of derelict cabins that sit within the high-desert landscape of the Mojave provide a necessarily familiar entry point into “Jackrabbit Homestead: Tracing the Small Tract Act in the Southern California Landscape.” This, the artist’s most recent project, is a bit like an iceberg with mass mostly hidden beneath the ocean’s surface: the research, digital media, photographs and other materials in the show merely hint at the full scope of her project, which digs into regional history and social movements, requires attentive listening and reading, and invites viewers to directly experience the desert.

In spite of the somewhat virtual and expansive nature of the exhibit, the photographs at the Culver Center for the Arts are the visual core of “Jackrabbit,” and they elicit an immediate draw. These images of abandoned structures succumbing to the inescapable pressures of entropy and the relentless incursions of the harsh desert environment suggest a narrative of failed dreams, yet they also reflect the idealism and pioneer spirit of the American West that set homesteaders on their hopeful track.

The subject of Stringfellow’s project, the Small Tract Act of 1938, colloquially known as the Jackrabbit Homestead Act, created opportunities for individuals to homestead federal land. The 1938 law differed substantially from the Homestead Act of 1862 with respect to the size of the homestead. Whereas the 1862 law provided for homesteads of 160 acres, Jackrabbit homesteads were only five acres. Most of the Jackrabbit homesteads were located in Southern California, concentrated in the Mojave Desert around the Morongo Valley, Wonder Valley and outside of Twentynine Palms, and were not especially suitable for cultivation due to the lack of water.

Documenting the Jackrabbit Homestead Act, a display case houses copies of Desert Magazine’s six-part series from July–December, 1950, “Diary of a Jackrabbit Homesteader,” along with a how-to article from Desert Magazine offering tips to would-be homesteaders; a copy of Five Acres of Heaven, a 1955 vanity publication showcasing the skills of a land locator for hire; and a handful of photographs of homesteaders on their claims. Stringfellow’s book, Jackrabbit Homestead, is available on a wall-mounted pedestal next to an iPod-listening station loaded with her six-part audio tour. And paired with each of Stringfellow’s 18 photos is a facsimile of the land patent—the homesteader’s equivalent of a deed of trust.

As a photographer, Stringfellow divides her attention between exteriors, which situate the cabins within the landscape, and interiors that personalize the sense of decay. Signs of occupancy, and the residue left after the owners’ departure, offer a more intricate human narrative than the iconic building-in-landscape. The exteriors find a visual precedent in John Divola’s “Isolated Houses” series (1995–98), in which Divola photographed dwellings in remote locations in roughly the same geographic location—titled by their latitude and longitude. While Divola describes “Isolated Houses” as a sign of man in the landscape, Stringfellow’s homestead exteriors are a sign of man retreating from the landscape and the indicators of his presence being re-absorbed by the desert.

Stringfellow’s photos, like Divola’s, reveal the vastness of the desert, the isolation of these modest structures and their insignificance in scale. The small size of the homestead cabins becomes clear from the Culver Center installation. The layout of a popular model—the Nugget Cabin—offered by a local construction company and illustrated on the gallery floor in black adhesive, reveals just how tight 400 square feet can be.

Stringfellow’s website includes the audio tour as a download and a companion piece for those who wish to see the remaining cabins in the open desert. The site also provides GPS coordinates of known cabins uploaded to Google Earth, and Stringfellow encourages others to upload the locations of cabins not currently documented. The inevitable demise of the remaining abandoned homestead cabins assures an end to the interactive portion of the project, which is one of the more interesting aspects of “Jackrabbit.”

Stringfellow’s project is compelling because it does not simply address questions of beauty, or why people find the desert alluring; rather, she traces people’s dreams and the tenuous relationship humans have with this extreme environment. It is sobering to note that Los Angeles is a similarly arid, (though slightly less so) region that also depends on imported water for its survival. Stringfellow’s project surveys the determination required to flourish. Her photographs, which engage in a discourse with highly romanticized images of human structures in the landscape, are both elegiac and optimistic.

-

Alex Slade

Through a process of intellectual, historical and geographic research, Alex Slade makes evident, and critiques thereby, the social forces that shape the American landscape. Landscape-oriented American photographers have been preoccupied with this issue since the 1970s, but have manifested the message poetically and metaphorically, as in most work associated with the New Topographics. Slade, by contrast, takes on a didactic air in his latest exhibition “What City Pattern?”—without subordinating aesthetic considerations to social ones.

Slade seeks to eschew as much romantic response as he can in his photographs, and certainly by including documents and sculpture-like elements in his exhibitions he presents evidence of ideals betrayed, sidelined, or co-opted. Slade does so with a deadpan worthy of New Topographics photographers such as Lewis Baltz or Stephen Shore, but also with a critical eye that clearly takes up the deconstructive outlook of a neo-social photographer like the late Allan Sekula. As much as these predecessors, Slade transcends the self-effacing, reportorial offhandedness and pretense at objectivity that make a virtual cliché of photo-journalism. He relies instead on the opposite cliché, making sure to make art of his imagery. This sets the realities of his land- and cityscapes, brimming with social implication, into starker contrast.

Slade’s landscapes, whether Midwest farmland or California desert, are gloriously bleak vistas, vast expanses visually distinguished as much by manmade as by natural structures. In these, Slade shows his New Topographic roots, but consciously admits the fact that he’s at least a generation behind: whereas the topographies of a Robert Adams anticipate a taming and degradation of nature, Slade’s show that the process has been pretty much completed. The results are neutralized, bland, rural non-sites much more akin to early Robert Smithson than to latter-day Edmund Bortynsky. Slade’s urban/suburban views conjure Smithson even more emphatically, brimming as they are with city centers compromised by outsize postwar buildings, which now have slipped into disuse and decay. Not a few of these buildings are themselves architecturally notable, for better or worse; and when he gets close to them, at least, Slade cherishes their details and their design aspects, à la Julius Shulman. Even there, however, Slade reveals corrosive forces at work—at work against each other, that is, architectural pretense coming up against the ravages of climate and vandalism.

In defining what Slade does, any number of older photographers can be cited, not to rely on them simply as stylistic tropes, but to place Slade squarely in a North American tradition of landscape photography, one that (as frequently done by Smithson) encompasses conceptual and land-art investigation. By including in his exhibition objects that exemplify the techniques of mid-century design and periodicals that promulgated these techniques and the (post-Bauhaus) attitudes behind them, Slade further conflates issues and practices relevant to the social landscape of postwar America. He thus underscores the Ozymandian tone of his photographs, articulating the prime postmodern plaint against modernism: no matter how well designed, the road to hell is paved with good intentions.