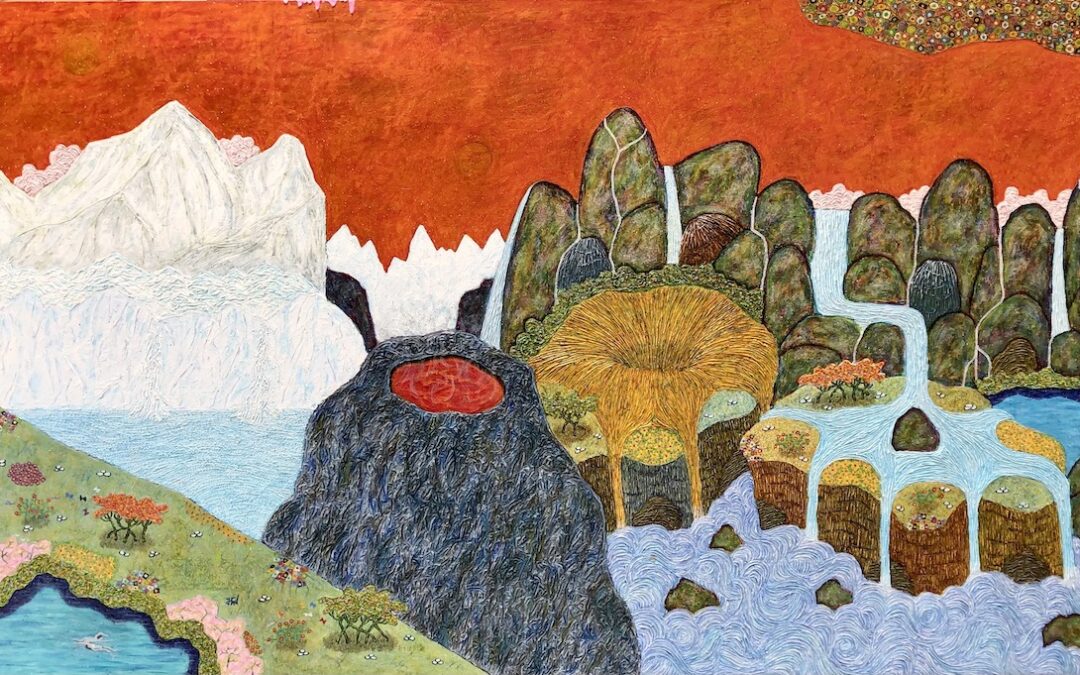

Naked, decapitated women were a favorite amongst the macho surrealists of the 1930s, projecting their desire and power onto phantom breasts and bellies. The female figures in Becky Kolsrud's surrealist paintings might also be missing heads and appendages, but they are...