Your cart is currently empty!

Tag: Kerry James Marshall

-

Remarks on Color: Eponymous Black

July’s HueEponymous Black is a stout, surly fellow with bad breath and a death drive that rivals Ophelia. His only friends are the pigeons in Central Park, and even they have their reservations, as often he’s deliberately stingy with the dissemination of the most coveted heels of sourdough bread. He regularly descends into madness, especially after eating figs, and this fact constitutes one of the unknowable mysteries of the universe. Eponymous Black disdains sun worshippers, those buffoonish, asinine people who purchase lawn chairs at the 99cent store, then set up a barbeque on the beach where they slather on sun tan lotion which promptly dissolves, gooey and salt laden, as for hours, they volley deflated balls over a makeshift net.

The entirety of the world derives from Black, just as everything must come from something and light is substantiated by the darkness, yet because he is an ego maniac, this fact is not enough to satisfy dear Eponymous, whose social negotiations include binge watching Orson Well’s entire filmography and picking radishes with an elderly woman from his mother’s retirement home. Eponymous Black is renowned for his collection of rare dung beetles, which he proudly displays on the mantle and sometimes shows off to his landlord, a petite and unassuming woman named Janine, who in her youth, had been a stand-in for the part of Mary Magdalene in Jesus Christ Superstar.

Eponymous Black works as a pharmacist’s assistant, trying to collect enough amphetamines to put himself out and over for good. No one ever suspects him of stealing as each month he manually adjusts Mrs. Adamson’s prescription to account for the missing pills. It’s an ingenious solution to the age-old problem of human malaise. It’s not that Eponymous Black wishes so much to die as he longs to be recognized, or as his esteemed father once put it, “if ya can’t get your name into the papers for doing something good, then, by God, do the worst thing you can think of. . . “and, well, so he did.

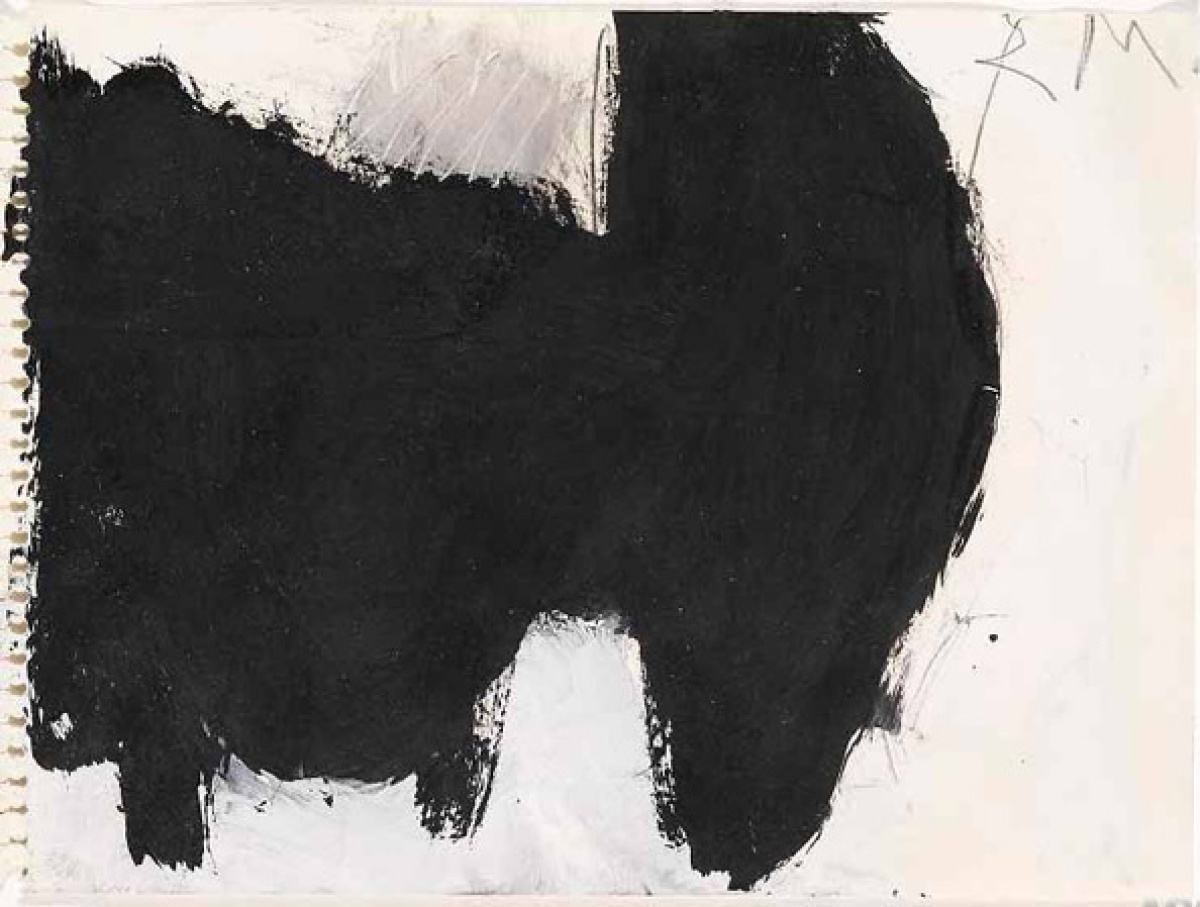

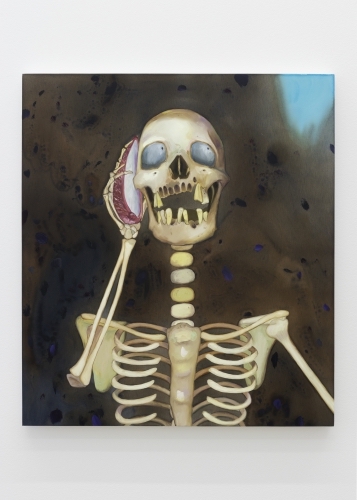

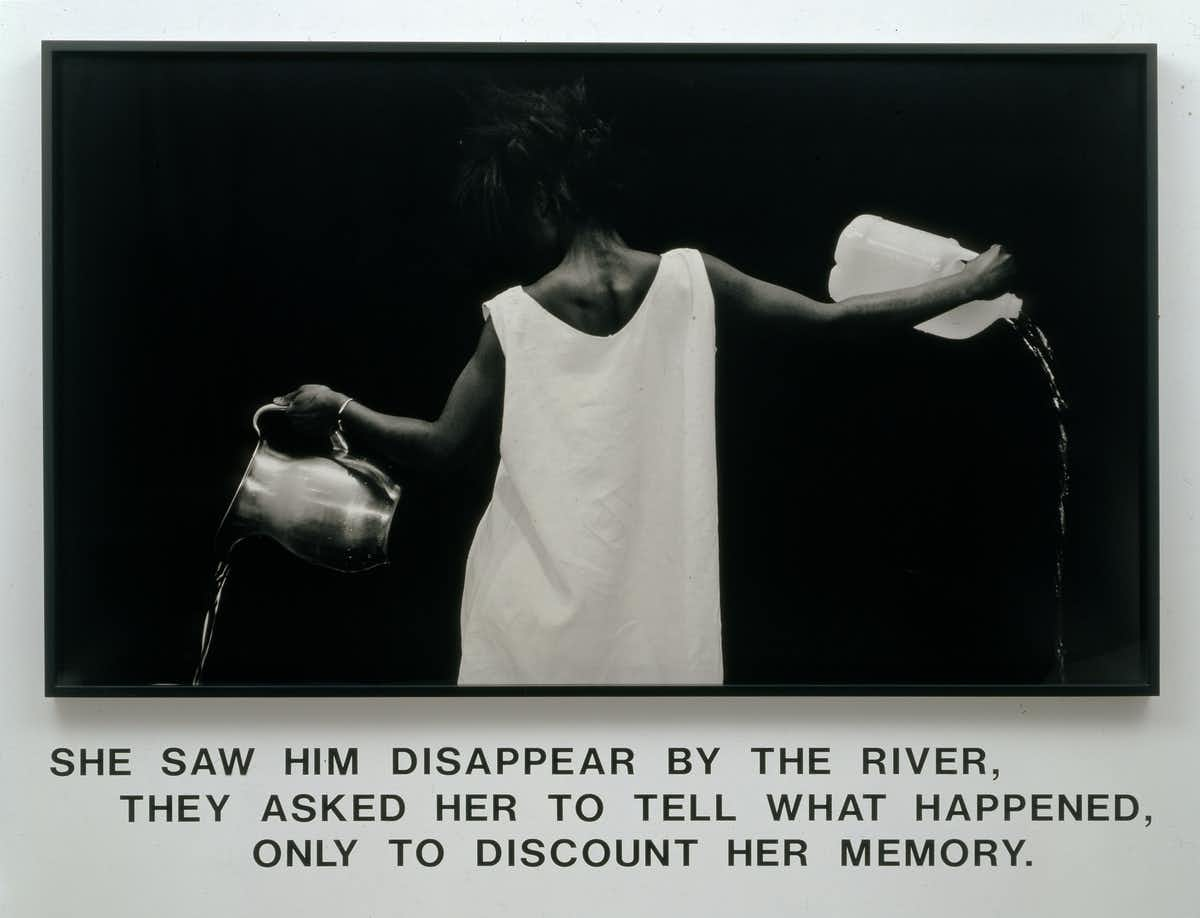

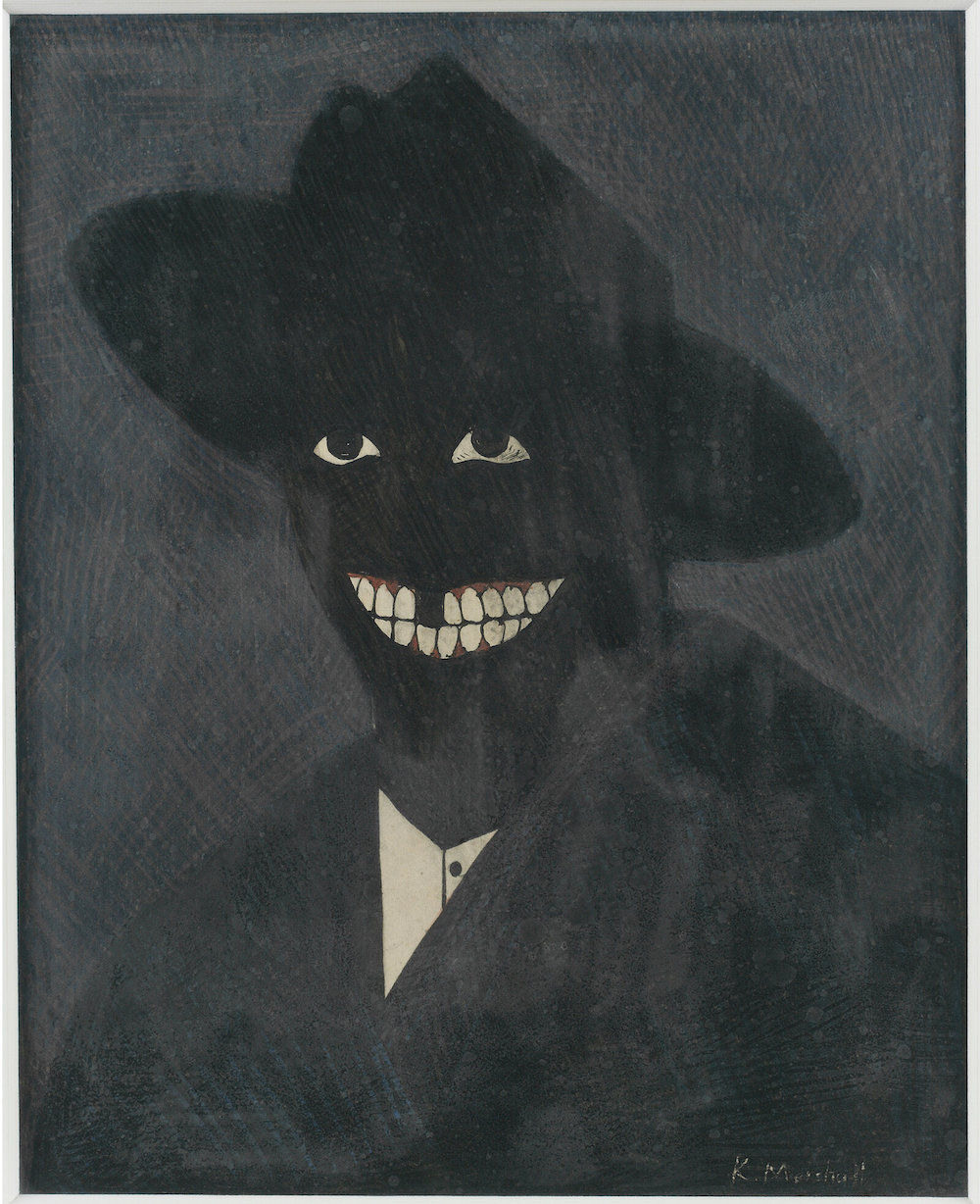

Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Still #16, 1979 Peter Heyer, Hello?, 2019 Mark Rothko, Untitled (Black on Grey), 1970 Robert Nava, Haunted Wolf House, 2019 Lavialle Campbell, Tassled-Obsidian, 2000 Aria Dean, Work (tout son col secouera cette blanche agonie), 2021 Lorna Simpson, The Waterbearer, 1986 Kerry James Marshall, A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self, 1980 Robert Motherwell, Elegy Study, 1949 Kara Walker, The Keys to the Coop, 1997 -

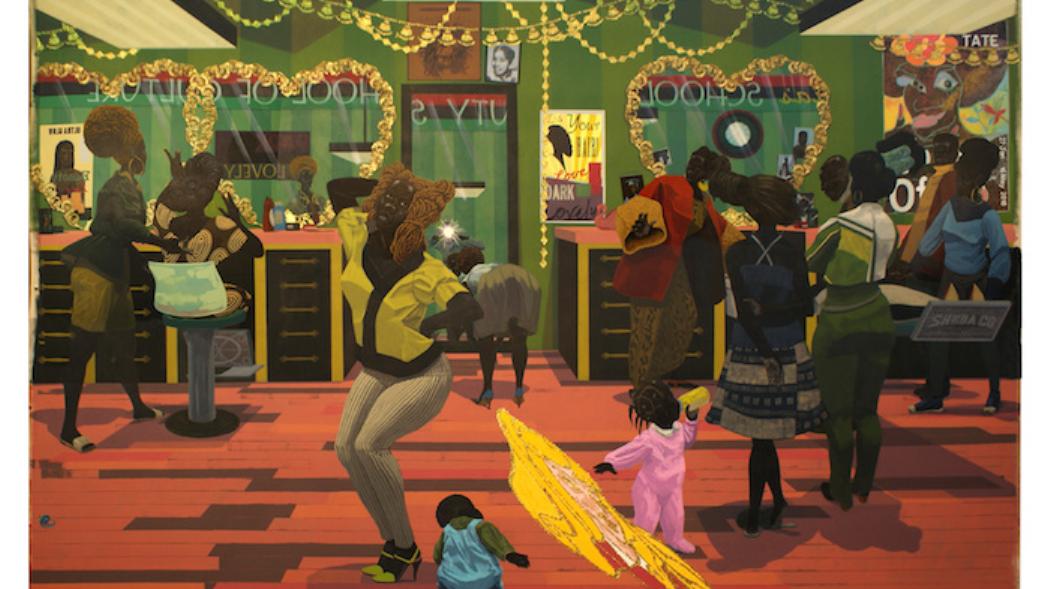

Kerry James Marshall: Mastry

Kerry James Marshall’s current retrospective at MoCA is less a ‘Pick-of-the-Week’ than a Must of the Year. Regardless of the particulars of each individual’s experience, it is a show that compels serious reevaluation of the historical canon of Western painting (and possibly representational and narrative painting generally), that artistic apogee we call the ‘masterpiece,’ and the tenuous perspectives offered by art and cultural history. This is as much about Culture as art (I imagine Marshall’s voice: ‘Listen up, Clement Greenberg…’) It’s about how culture responds to a power structure and how its art absorbs and channels a dominant political narrative; how cultural authority channels and reflects – in varying degrees of uncertainty and subtlety – that power structure. More importantly, it’s about how those terms are subverted or entirely reversed. Of course it is a political art. It is also an art of idealism. It embraces the same canon it challenges, and says ‘Look at me.’ For those of us privileged to have had broad exposure to Western painting to the extent that we recall images of Africans or individuals of African descent in works of European art, consider who those individuals were and where they were in those representations. Consider the black maid who figures prominently and distinctively in Manet’s Olympia. The courtesan ‘Olympia’ may be nothing more than her pose or her job description, but that is the girl the world is coming to see, the girl the political power structure supports, and the device Manet has chosen to challenge one segment of that power structure. And in 1863, that beautiful, well-dressed maid was probably one of the lucky ones. And then the maid(s), (fill in the blanks: stable boys, coachmen, valets, blackamoors, natives on an African savannah) recede again into the backgrounds or disappear altogether. With a frontality that matches Manet’s, Marshall addresses appearance on every level – from the casual, almost fleeting observation, to the consciously and directly representational, to the formally evidentiary and broadly symbolic; and finally (and sometimes equally directly) to the underlying narrative that supports or challenges the perception of those representations. This extends to the importance of the frame itself (and scale: these are large paintings) – addressing the ‘narrative’: what it tells or reveals, and leaves out or represses (and sometimes, as Helen Molesworth, the show’s co-curator and editor of its catalogue, might put it, both simultaneously). In contrast to that European benchmark, Marshall’s treatment of the figure ranges between a hard schematic realism and something more ‘magical.’ His approach is allegorical, rather than strictly historical (or ‘memorial’), reaching back to where that ‘disappearance’ actually begins – the medieval and early Renaissance. Alongside those hard-scraped figures, bluebirds arc and scrolls or music staves unfurl ‘keynote’ messages or blunt broadsides. Also frankly dissonant notes both pictorial and stylistic: a ‘paradise’ not lost, but corrupted and certainly disrupted – these are allegories replete with contradiction. As Molesworth put it in one of her gallery talks (which I encourage prospective viewers to check out), “You can’t resolve this; you can only be with this.” Whatever the duration of your visit, Marshall’s paintings will be with you for a long time.

The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MoCA)

250 So. Grand Avenue

Los Angeles, CA 90012

Show runs thru July 3, 2017