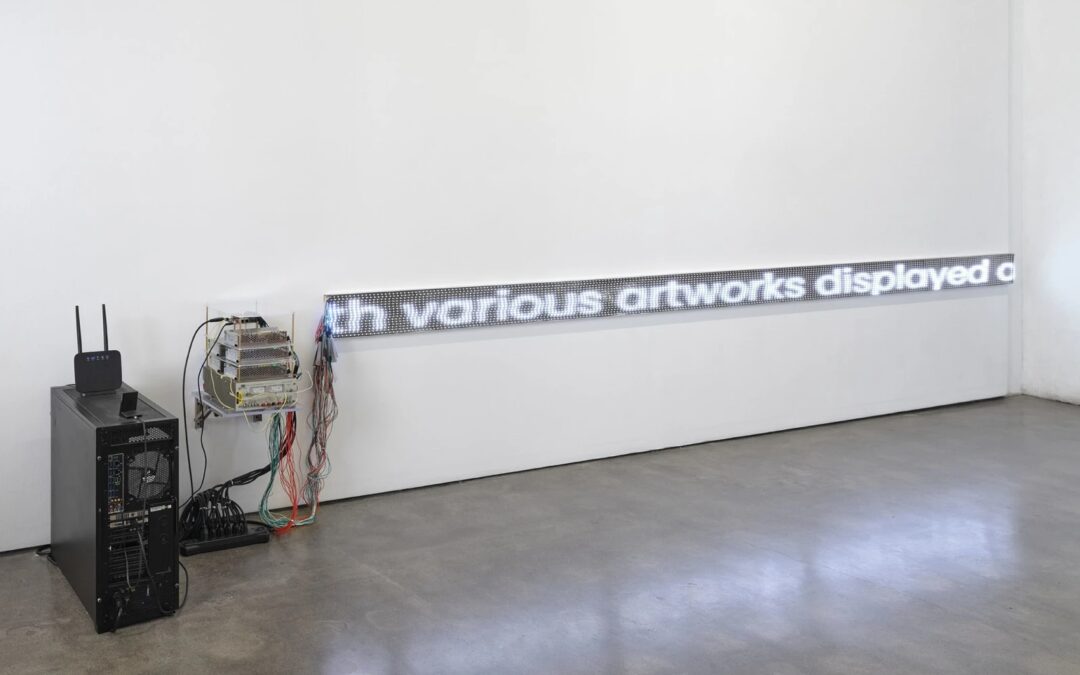

Christine Sun Kim’s work leaves little room for misinterpretation. Clarity, for Kim, is a reality of survival. “American Sigh Language,” the artist’s recent solo exhibition at François Ghebaly, makes it clear: for Kim and other Deaf individuals, intelligibility serves...