Your cart is currently empty!

Tag: feminist art

-

NICE DOGGIE

Inspiration must have been in short supply the day in 2012 that Sue Williams started Dallas, her painting featured at this year’s Frieze art fair. Like most artists, Williams undoubtedly set out to create something unique, a painting for the ages, as masterpieces are often touted. But somewhere along the line it became, not the subject of a joyous collective experience, but confirmation of Williams’ onanistic creative process; her art fantasy apparently fodder for aesthetic masturbation. Consequently, if a Pollock drip painting can be called ejaculatory, then in the interest of gender equality this Williams painting is a gusher.

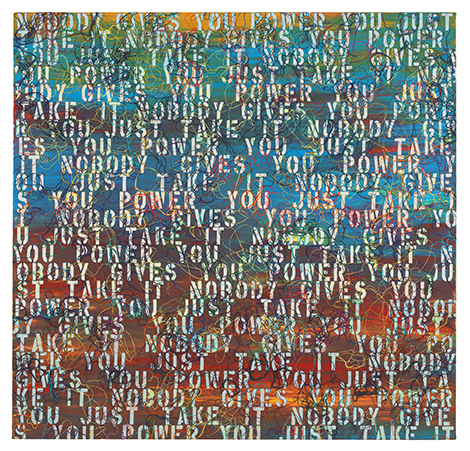

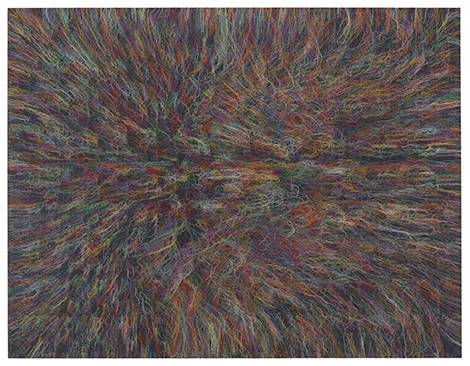

Sue Williams, Dallas, oil and acrylic on canvas, 60 x 60 in., 2012. Photo courtesy 303 Gallery Amid the painterly chaos of Dallas, the head of a man peers out through the drips and smears that, quite literally, deface him. Even so, he is recognizable as a typical Feminist presentation of the classic “Fifties Man” white male oppressor. His degradation is to be expected of course, for Williams’ “world of provocative sexual politics” demands a sacrifice from the patriarchy. Also, according to a 303 Gallery press release from 2010, “Williams (work) can illustrate a conclusive and all-encompassing conjuring of everything at once.” Which explains why the blend of text, crude coproid brown blobs, and abbreviated diagrams in Dallas is essentially an upside-down roadmap to nowhere. Still, in the face of such statelessness, Williams has, like Google Maps, helpfully included the names of specific locations such as Throgs Neck in the Bronx and the Barclay Center in Brooklyn. That, plus pointless verbiage like, “luxury, privacy and the magic of Disney,” confirms that a whole lot of everything can amount to nothing.

Photo by Anthony Ausgang Other than the incontrovertible fact that brushstrokes travel in a certain direction, Dallas seems directionless. Perhaps that is why Williams felt it necessary to include the image of a dog’s asshole; something had to take this piece somewhere. And as far as remarkable totems go, an anus is guaranteed, as this blog evidences, to garner comment. Although her painting is indisputably High Art (why else would it be at Frieze?) the use of an asshole as a major element reveals a weak attempt by Williams to appear an anti-aesthetic revolutionary. Regrettably for her, Low Brow Art is often similarly scatological, but work done in that genre is generally structured around a recognizable narrative. Within that paradigm, a dog’s asshole is critical in understanding specific pictorial storytelling. That’s not the case in Dallas, where the anus seems to be included, not as an element necessary to deciphering this painting, but as a device for making it stand out from many otherwise similar paintings by Williams. As such, the anus may be fake news, but it’s a brilliant tactic. Still that’s about it; Williams’ oeuvre already proves that she’s adept in parlaying offensive content into a lucrative art career. But repetitious use of lurid imagery does lessen its impact; perhaps that’s why most people examining Dallas at Frieze didn’t seem to care about the canine sphincter. But that’s to be expected; after all, opinions are like assholes, and every dog’s got one.

-

Feminihilism

Feminism is an ideology that powers political and social movements dedicated to establishing gender equality between men and women. As such, it serves as inspiration for artistic exploration of the various issues involved in that process. First-generation feminist artists like the late Carolee Schneeman, rejected the male-dominated scene of the 1970s, refusing to be, in her words, “cunt mascots on the men’s art team.” Forty years later, the changes advocated by these pioneers have created a new generation of women artists who don’t identify as feminists. This attitude is perhaps best represented by the “women initiated” NGO, Code Pink, a “social justice movement” that encourages people of all genders to participate in its activities. The importance of the inclusion of men in such organizations cannot be downplayed, as it shows that many Millennial women believe the era of close-combat for gender equality is over. For like-minded women artists, this means that their starting point is no longer the difference between the sexes; in fact, male privilege doesn’t even chart as an issue. While emphasizing the obsolescence of binary sexual identities, Feminihilism simultaneously dictates the abnegation of any masculine influence on Millennial women artists.

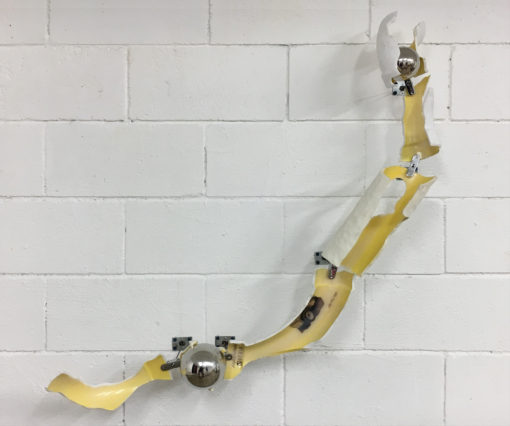

Sofia Sinibaldi, Untitled, mixed media, 36 x 36 inches, 2019. Photo by Anthony Ausgang Considering today’s culture wars, any work of art done by a woman has societal implications. In AX, their two-person show at the Red Zone gallery, Natasha Romano and Sofia Sinibaldi neatly evidence an aesthetic allegiance to their gender. Both artists have unique approaches but the absence of sexual politics in their individual works confirms their commitments to a strictly feminine paradigm. Consequently, Sinibaldi’s sinuous wall sculptures are reminiscent of the blocked fallopian tubes symptomatic of an ectopic pregnancy, and the flood of red grounding Romano’s floor sculpture suggests menstruation and/or sexual violation. Still, the heart-shaped negative space she employs registers a modicum of romance, but there’s no indication whether that’s hopeful or ironic.

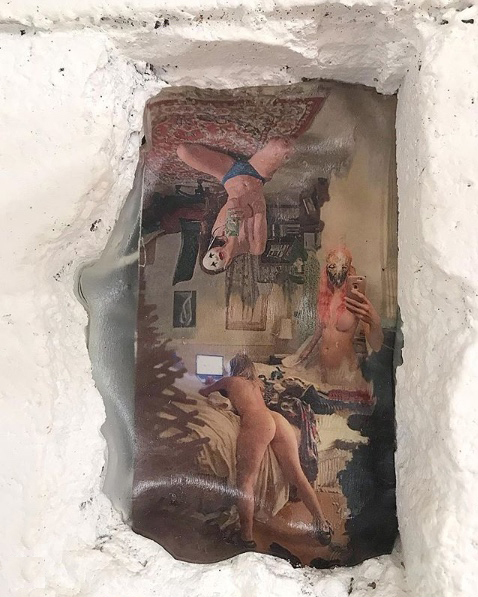

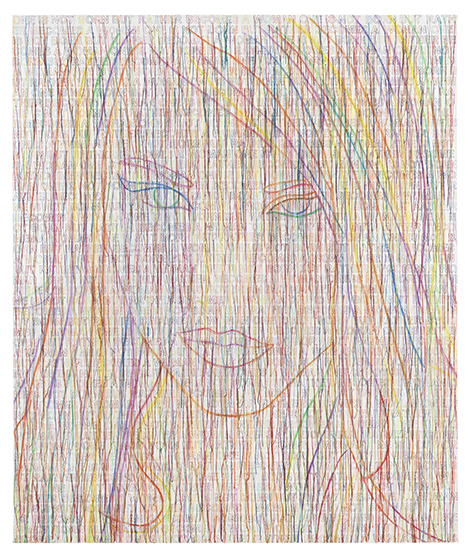

Natasha Romano, 1 2 3 red blond brunette anon screens, mixed media, 2019. Photo courtesy Natasha Romano As Millennials, both artists use contemporary vernacular when problem solving. So, it’s not surprising that Romano’s wall piece, 1 2 3 red blond brunette anon screens, addresses self-identity issues via the depiction of social media. Two of the figures are taking selfies but their faces are paradoxically obscured by masks, essentially promoting anonymity over individuality. The third figure, although she is communing with a computer, is isolated by her lack of a phone, putting her more in the role of a lurking observer than participant. However, maybe that duality is what appeals so strongly about the internet; playing both parts can have a heady appeal.

Natasha Romano, Diamond Headed Honey Snake, mixed media, 72 x 48 x 48 inches, 2019. Installation photo by Anthony Ausgang But the main piece in AX is Romano’s magnum opus, Diamond Headed Honey Snake, a mixed media floor sculpture that dominates the gallery. Describing herself on Instagram as “sculptress n garmentiste”, in this piece Romano makes smart use of the skills she gained as a seamstress assembling her clothing patterns from non-traditional fabrics. Consisting of small cairns, rattlesnake rattles, natural and synthetic materials, and lots of different dried red sludges, the sculpture is epically incomprehensible. But perhaps being psychically cast adrift by this “shock of the new” is the reaction Romano expects, because with her multi-faceted talents, she rewards scrutiny with devilish and bizarre details. In just one part of the sculpture, a flaccid snakeskin encrusted with wasp’s nests that ooze plastic is intertwined with sewn-together vinyl strips featuring figurative emoticon-style hieroglyphs. This accumulation, held aloft over the dry red tide by trestles that look like webs made by spiders on meth, disappears into a mysterious box from which the spill emanates. As a piece on its own, it’s impressive; as a component of the whole assemblage, it’s spectacular.

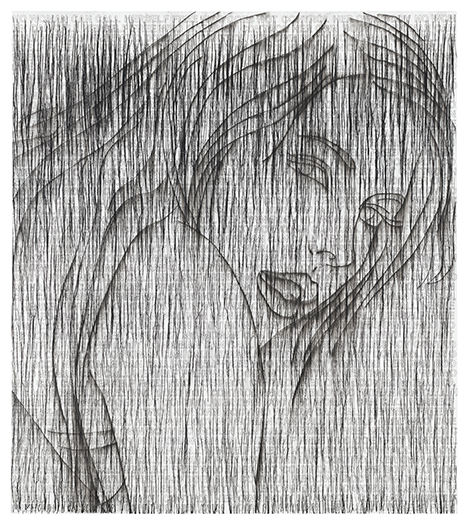

Natasha Romano, Diamond Headed Honey Snake, mixed media, 72 x 48 x 48 inches, 2019. Detail photo by Anthony Ausgang In terms of cultural progression, today’s art would not be possible without the efforts of previous generations. But whether or not contemporary artists actually owe any acknowledgement of that is debatable. After all, at this point do we still really need to thank 19th Century French Impressionists? The trick, as both artists show, is to update the message; perhaps that is honor enough.

Red Zone, 840 Chestnut Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90042-3041

Open by appointment (818) 524-8701