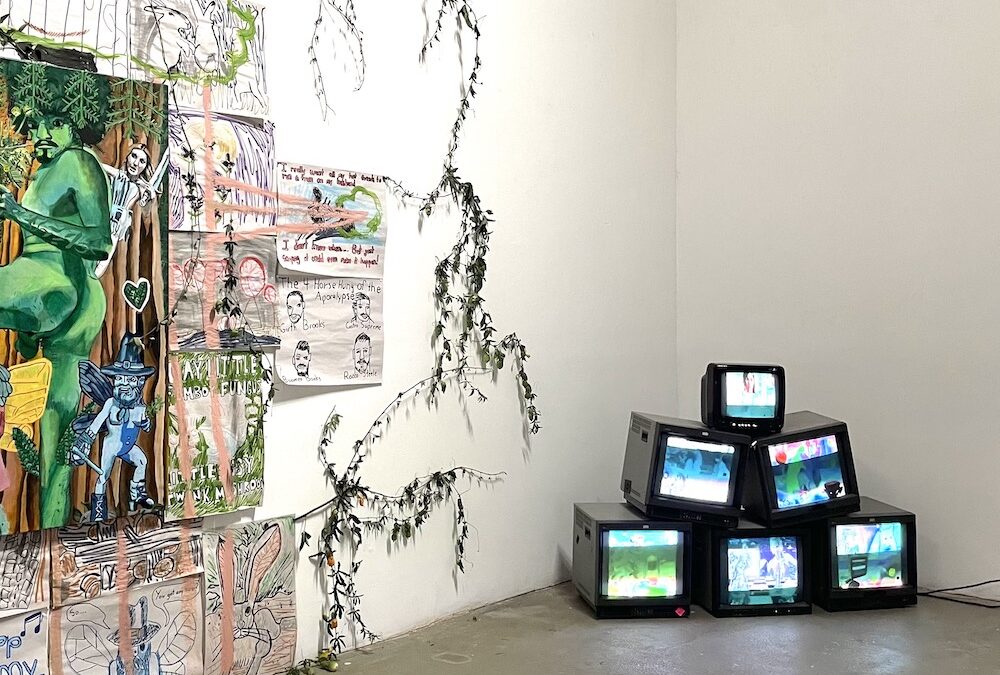

After parking on an ominous street, dodging detritus on the sidewalk and being ushered through the door by an equally ominous bouncer—we enter a sprawling fog-filled industrial space just south of DTLA. Loud music plays, neon flashes and the walls are literally...