Your cart is currently empty!

Tag: contemporary writing

-

Publication in the Age of Negation, Part VIII

Laying a False Trail Across the Visceral EtherNobody is reading this.

No sooner have I started to write a sentence than I’m plunged into bitterness and despair. Sitting down to write has become too great a test of my moral and spiritual strength: I am immediately mystified as to why it is so difficult to get my work out there when others, whose works are bereft of conviction, vitality, originality or purpose, who have nothing new to say and no new way of saying nothing, don’t seem to experience the slightest difficulty getting their pointless prose published. It requires too much effort to stifle the resentment that floods forth as a result of these grueling, draining, ungovernable thoughts. I am immediately conscious that nobody is going to be reading what I write, and oppressed by a morbid awareness of all the garbage that is out there.

“Yes, by all means, send the whole thing,” wrote Jim Brooklinen, swiftly responding to my offer of sending him my novel in its entirety. “My days are emptier than a weaver’s shuttle, and your novel might be just the curative I need.”

It seemed that the sun was going down on this venerable New York literary man, and judging from the elegiac tone of his email, in which he misquoted a line from the Book of Job, it didn’t seem that he anticipated his days becoming any less empty in the foreseeable future despite the potentially medicinal qualities of my prose. He was afflicted with an undisclosed, possibly terminal medical condition, and had become something of a shut-in, cared for by Penny, his devoted wife of many years.

I exhumed my manuscript and read a few passages from it. Despite having been consigned to a premature burial over two years ago, it was still alive, it still breathed. That lifted my spirits, slightly. Maybe I really did spend four years prioritizing this thing so that I could return to gloat over it from time to time with the satisfaction of having achieved something I hadn’t thought I was capable of. Maybe it was a purely private and self-indulgent endeavor, and perhaps it would always remain thus. That was something: at least one person was deriving pleasure from all this work, even if it was myself.

But perhaps what was alive to me, in the knowledge of all that I’d put into it, might be dead to somebody else. In the same way that I wasn’t sure if I was seeing what others saw when I looked at my reflection in the mirror, when I re-read passages from my novel I couldn’t be certain if what I was looking at was only the idealized version of what I was hoping to achieve – that which vividly existed in my head but not necessarily on paper. There was no proof that it possessed any life beyond that insular sphere, especially when I almost never sent it out anymore, least of all to potentially receptive parties.

I sent the whole thing to Jim Brooklinen.

Caspar David Friedrich, Sunset, 1835. Eden Gaperdiveve, the publisher of Hallway press, shuffled on to the smoking patio, somewhat palpably out of sorts.

“How are you doing?” he asked in a tone that gave the impression I could take some credit for this departure from his usual air of self-assured abstraction.

“I have arrived at a standstill,” I said.

“Haven’t we all?” he said, defensively.

“No, not all of us. Unfortunately not.”

“Is this conversation going to be appearing in Artillery magazine?” said Eden, emitting a wary and mirthless laugh.

“You needn’t worry about that,” I said. “You can speak freely around me. I’m taking a break from writing those essays, as you can’t fail to have ignored.”

“Because,” he continued, “I never said any of that stuff you supposedly transcribed in the last article. How can it be me if you invented all the dialogue?”

“I didn’t say it was you. That’s why you have a different name.”

“That name…”

“You don’t like it?”

“I can’t even pronounce it.”

“If you don’t like it, we can change it. That’s not a problem. D’you want something that sounds more like your own name or something different? I’ve got a few ideas. What d’you think of Earl Sateriale?”

“No way.”

“Eric Rechteffizient?”

“That’s even worse,” he groaned. “Would it be too much to ask for something a bit shorter? Something I can pronounce, at least.”

“How about Emil Quadtas?”

“That’s a bit better. But not Emil, Eden’s fine.”

“Not a problem, whatever you say. That’s your name from now on, Eden Quadtas. You might get a recurring role.”

“But what’s the point?”

“You’re just a point of departure.”

“A point of departure?” Eden repeated, sounding slightly hurt.

“Yes, for further excursions into the merits of autofiction and related bullshit. But you’re right, the character has shed his origins. I should never have suggested it was you in the first place. You probably wouldn’t have recognized yourself.”

“Oh, I would have recognized it,” said Eden, not without a trace of bitterness. “Hallway books, it’s pretty obvious isn’t it?”

“Look, this is getting silly,” I said. “I don’t want to get all meta. It will exhaust people’s patience. This is supposed to be a roman-a-clef.”

“That’s just another word for autofiction,” said Eden.

“You should know,” I said. “You’re the one that’s publishing an anthology of so-called autofiction. Metafiction, autofiction, call it what you want, and why call it anything: because it’s going to be taken more seriously if you put a tag on it, like a corpse?”

“It’s a social comedy,” said Eden, with a despairing sigh.

“You can say that again,” I said. “Just call it literature, if that’s not aiming too high.”

“You realize,” said Eden, “that what you’re doing is more true to the spirit of autofiction than most of the works that fall under that category.”

“That irony hadn’t escaped me,” I said. “And if the novel itself ever does get published, it’ll be taking it to another level considering all the overlap and cross-referencing.”

“Edouard Leve must be turning in his grave,” said Eden, referring to the great French artist and writer who took inventive autobiography to new and suicidal lengths. His novels, Autoportrait and Suicide, had unwittingly become the foundational works of an artificial genre that he would probably have wanted nothing to do with.

“He’s great,” I said. “But his books are almost entirely autobiographical. Most of these writers are incapable of creating fiction, myself included. The term itself implies a combination of fiction and autobiography, which would amount to the majority of fiction throughout the ages. Thomas Bernhard wrote so-called autofiction, Proust, without a doubt, wrote autofiction, as did Goethe. What isn’t autofiction? That would be a better question. This so-called genre exists merely to flatter the limitations of it’s self-proclaimed practitioners, who wouldn’t merit any consideration if they hadn’t attached this ridiculous handle to the cumbersome baggage of their ineffectual prose. You’re not breaking new ground by giving something that already exists a different name. Anyway, it’s hardly worth discussing.”

“Then why can’t you shut up about it?” said Eden, somewhat uncivilly.

“That’s a good question,” I conceded. “It’s embarrassing, pitiful really. Let’s move it on a bit.”

Caspar David Friedrich, Two Men Contemplating the Moon, 1830. “John ~ I have finished (finally) reading your novel, and am relishing the sensation of having fortified myself on a lavish and satisfying meal ~ a rare pleasure in these days of starvation rations. I apologize for having taken so long but it had to be savvored in small helpings, owing to the singular richness of the work. Maybe my powers of judgment have been pharmaceutically clouded of late but I can’t help thinking it’s the finest new work of sustained prose I’ve read in a very long time. You are a 21st century Laurence Sterne and you have achieved something wholly fresh, original, consummately executed and fully realized. I only wish my old confrere and fellow hell-raiser, Barney Rosset, were still with us, as I feel certain he would join me in extolling these undeniable qualities. In his sorely lamented absence, however, I do have a few ideas about other parties amid the more enlightened and discriminating echelons of the publishing world that might be receptive to our cause, and will contact them forthwith. Don’t get your hopes up as I may not have so much pull these days, but I’m but I’m going to tug hard at every possible string to get this marvelous novel the sort of exposure it richly deserves. Tell me: would it be all right by you if I selected a few passages and sent them out to these parties?”

Jim Brooklinen’s rapturous response was, to say the least, heartening. Not only was this highly respected and influential New York literary man heaping unconditional laudations on my modest novel and taking up my cause—referring to it now, indeed, as “our cause”—but he was also confidently stating that the late Barney Rosset—a titan of avant-garde publishing, the founder of Grove Press; the man responsible for bringing Beckett and Genet to American readers—would have shared his excitement. A firm foundation upon which to base realistic hopes for publication had surely been established, and the presence of fewer typos than usual suggested that Jim was in better health.

This is Part VIII of an on-going series. Please see previous installments: Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V, Part VI and Part VII.

-

POEMS

“shift work” by Evan Evans; “Enduring Romance” by John Tottenhamshift work

twin heads pillow

moments away

only seats left in the front

the forgiving distortion

the forgetting of plot

so grateful

that the light should bow

to take the shape of your mouth

a movie where she’s

so tired

from watching him

sleep

all day

—Evan Evans

Enduring Romance

There was a time when you were charmed

by my lunging, and when I found your ignorance

more endearing. But that was long ago,

when love was new and our every precious moment

felt like sunlight glittering upon the edge

of a gently breaking wave. Now closeness

means chaos, and every dreaded moment

brings me closer to my grave.

Where does all this clumsy thrusting end?

Half-mad, greedily sucking on the

desecrated manhoodof the absentee father; desire meets boredom halfway

in a stalemate of discontent, a deep and selfish love

that can only thrive in a moist environment.

—John Tottenham

-

Poems

“Silicon Valley” by Rhiannon McGavin; “Vanity in Vain” by John TottenhamSilicon Valley

A cloud is the earth displaced for tracks of cable underground, underwater

A stream is the friction between content and a beckoning hand

To kindle is to adjust the climate dial in a server farm

An antenna is the arc of pesticide as it is sprayed from a plane

A bug is the noise emitted by neon signs

A web is the section of sky covered by a billboard

A nest is the time elapsed between waking and sensing an advertisement

An echo is the decomposition rate of post-consumer technological products

An amazon is the unprocessed pulp for one holiday’s supply of shipping boxes

An apple is the leaked transcript of a board meeting

A seed is one black redaction mark

To phish is when a red tree blooms in the warmest recorded January

A story is what disappears after 24 hours underground, underwater

Memory is less expensive each year

Memory is the sound a forest makes as it is felled

Memory is the thing that waits for room to grow

—Rhiannon McGavin

Vanity in Vain

To give up or give in,

to cease to take solace in

the things that I take solace in,

and give in to wanting

what everybody else wants.

That way lies ruin.

As vain, in vain, and unrewarding

as it’s been, the losing battle

I’ve chosen still beats the alternatives.

There’s no way out now, no return

to the collective dream.

—John Tottenham

-

Poems

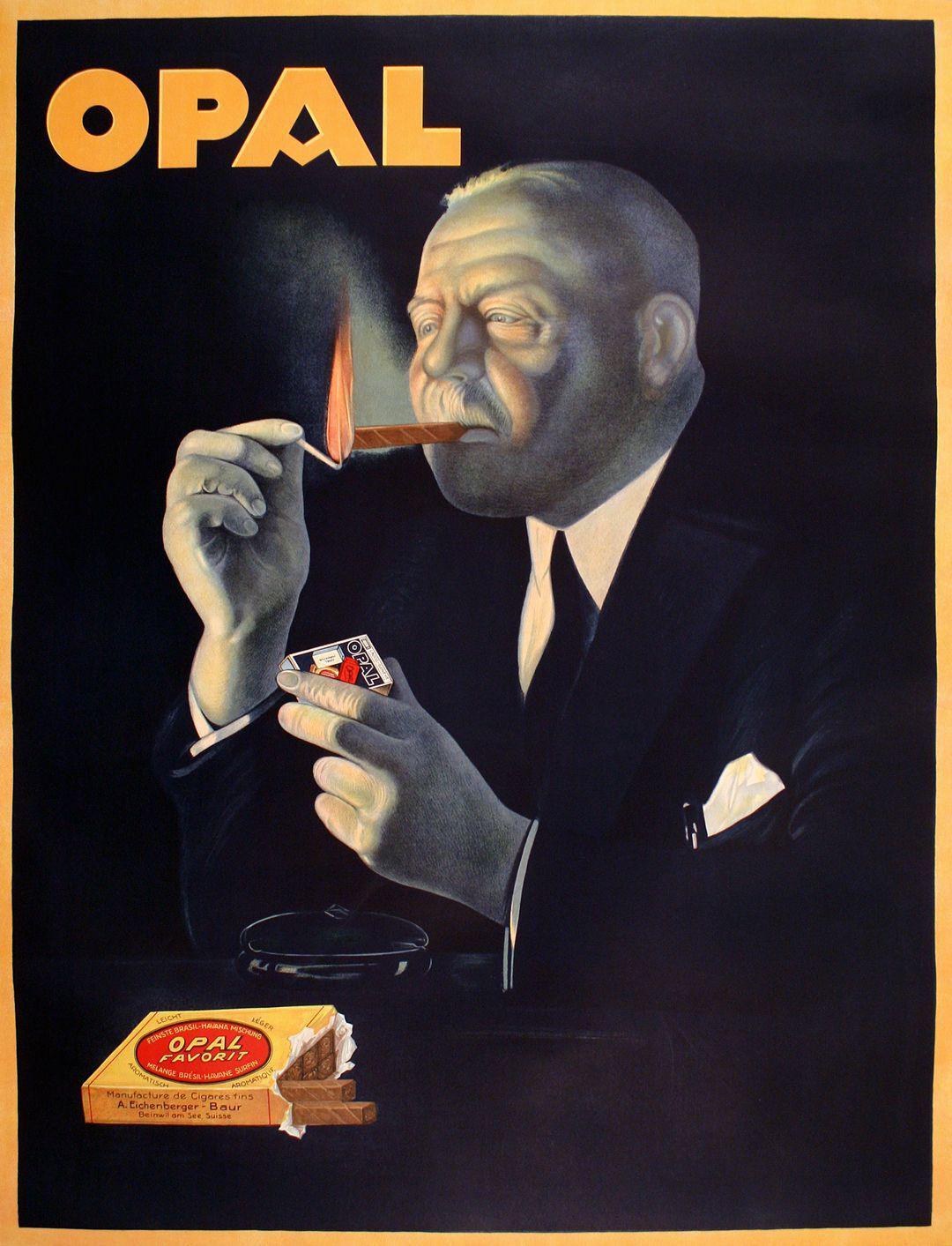

“Kiefer Lights a Big Cigar” by Klipschutz; “The Poet’s Garden” by John TottenhamKiefer Lights a Big Cigar

& waves the heavy machinery into place

He rearranges the rubble

speaking whichever language suits the occasion

He & Tony saunter through a tunnel in the South of France

“It’s my gesture” is what he says about his art

His use of lead & straw reminds me of a Jack Gilbert poem

Kiefer & Werner Herzog must never meet

If they have, they must never admit it

(When Gerhard Richter met Stockhausen

neither one was left unscathed)

Kiefer carries the weight of the world on his shoulders

& shakes it off with a flick of his cigar

—Klipschutz

The Poet’s Garden

Without these words, without these needs,

how much simpler life would be: free

from invidious and irrelevant comparisons,

resentful longings, and obscurely realized

self-actualizations: a life less whole,

a lifeless hole… but a destiny, at last,

within my control – striving

only towards resignation,

a worthy goal.

—John Tottenham