Your cart is currently empty!

Tag: commentary

-

Publication in the Age of Negation, Part VII

Sex, Drugs and Bad WritingI hadn’t sent the novel out in a while. In fact, I hadn’t sent it out in months. What was the point? Even if they loved it, they didn’t want it. At this point I was too dispirited to send the work out or describe the ensuing demoralization. But I needed to send it out in order to have some fresh rejection to write about. Otherwise I had nothing to say, and with these exaggerations and fabrications, I was only perpetuating frustration, laying a false trail across the visceral ether.

I sent the same fifty-page section that Melinda Waterform had ignored to Jim Brooklinen, a former editor of The New York Times Book Review. I had enjoyed a warm acquaintanceship with this eminent old East Coast literary man for about ten years and he had always encouraged me in my modest endeavors. I had been reluctant to send him the novel, or any portion thereof, as I had heard him complain about the unsolicited works that were still inflicted on him by pushy writers when he was retired and declining in health. But during the course of our occasional correspondence he had asked to see the novel when I had told him what I was working on.

“Dumb up the volume, because if you turn it down the quality of conversation will have to rise,” I said to Eden Gaperdiveve when I encountered him in a popular bar on the eastern end of Sunset Blvd.. A deejay was blasting classics from the halcyon punk and post-punk era – vicarious nostalgia for today’s youth, who hadn’t found anything better to replace it with.

“At least he’s playing good music,” said Eden as a highly compressed wave of negative elation—Mannequin by Wire—surged through the small room. Eden was a charming and erudite young man of letters. He ran a small press and arranged some remarkably democratic literary events around town. He seemed to care.

“That’ll be nine dollars,” shouted the bartender as a tattooed hand placed a bottle of cheap Mexican beer in front of me.

“I’m sorry.”

“Nine dollars!” he barked back.

“I didn’t order two, just the one!” I shouted back, and grudgingly threw down two fives, resenting the one dollar tip. This was a high price to pay for the privilege of having one’s senses assaulted in a claustrophobic sty filled with young people who were learning how to drink, learning how to smoke, learning how to hold a cigarette properly. Ten years ago the bar was a hole in the wall with a curtain in the doorway, and it was off-limits to well-heeled young Caucasians. Never mind…

“I’ve really been enjoying your rejection articles, especially that last one,” said Eden.

I thanked him kindly.

“It was funny,” he said, “but sad too.”

“Tell me about it,” I said, taking a sullen two-dollar slug of the overpriced beer.

“I’m glad somebody’s taking a roman-a-clef approach to the local literary scene,” said Eden. “I dug the Jeff McClimon cameo.”

“What’s that?” I said, straining to be heard over the chorus of Chinese Rocks.

“The writer you ran into outside your apartment. That was Jeff McClimon, right? It had to be.”

I was flattered that somebody was paying attention enough to make such assumptions, but also slightly disturbed that the character had been identified so easily when I hadn’t revealed anything specific about McClimon. “Jeff could easily recognize the encounter it’s based on,” I said. “I don’t suppose there’s much danger of him reading it though. He probably has better things to do, like his own work. How did you figure that out anyway?”

“He’s local and he wrote a blurb on the back of Neville’s book,” said Eden.

“You’re too sharp for your own good,” I yelled back. “What makes you think that was Neville’s book?”

“Because you were complaining about it when we were talking about Alt-Lit a couple of weeks ago.”

“Not exactly,” I lied. “It’s a mishmash, a composite. Most of these characters are composites. Situations and sentiments get transposed and shifted around. It’s taking shape as we speak.”

It was true, however, that the earlier-derided Alt-Lit author, Zander Valvitcore, could have been based on a number of people, not just Neville Smirek. The literary world currently abounded with self-published, micro-press-published—and increasingly, major-press-published—transgressive young writers. It was strange, but in recent years becoming “a writer” had come to be seen as a glamorous occupation, especially for inexplicably affluent young people who had nothing else to occupy their time with, and such writers as Neville Smirek were encouraging this new perception with their phantom income-fueled globetrotting lifestyles and aggressive social media presences. They threw publication parties in nightclubs that were more like raves than literary events, surrounded themselves with models and ‘influencers’, and ingested copious quantities of molly and other designer drugs. These salons and soirees were instantly over-documented on Instagrim for the convenience of the uninvited and the hateful doom-scrollers among us. Which would all be fine, if the writing itself was any good. Which it usually wasn’t. These days there were simply a lot of people that liked the idea of being a writer; they thought of themselves as writers and described themselves as such on their social media profiles, although there was very little writing going on compared to the amount of time they spent hustling and being fabulous. But the effortless enablement of the internet made it possible for them to entertain such illusions.

Edward Kienholz, “Barney’s Beanery,” 1965. “Why do you even care?” said Eden.

“I resent people that haven’t made the same futile sacrifices that I have,” I said.

“Because they haven’t paid their dues?”

“Something like that… since when was the deejay elevated to the status of priest? This guy isn’t even spinning records. He’s playing music off a fucking laptop,” I said, deliberately changing the subject. Although I objected on moral and syntactical grounds to some of the authors he handled, I wasn’t entirely opposed to the possibility of being published by Eden’s emerging press: they were getting some favorable attention and had decent distribution.

“Let’s go outside so I can smoke,” said Eden.

We walked through the crowded bar to the crowded but somewhat quieter sidewalk.

“I was just talking to Suer,” said Eden, lighting up an American Spirit.

“I’m sorry…”

“Emgona Merage’s husband.”

“I thought she was a lesbian.”

“She is, but now she’s married to Suer Wightman, who just transitioned. They are a writer too.”

“Naturally.”

“They just wrote their first novel but they can’t get it published, which is funny because Suer is represented by Charlie Byars.”

“Never heard of him.”

“Really?” said Eden in disbelief. “Charlie Byars is one of the biggest agents in the country.”

“Like I said, despite the endless bellyaching in the articles, I haven’t really made an honest effort to get my novel out there. I just like complaining about it. How come this Suer person is represented by such a big agent if it’s his first novel?”

“Charlie Byars represents Emgona Merage…”

“Right. I see… So he’s represented by the biggest literary agent in the country, he’s married to a highly successful young writer, he just transitioned, and he still can’t get his novel published.”

“That’s right,” said Eden.

“Very odd,” I said. “He’s made all the right moves. A rare case of nepotism not working. Maybe the novel is crap.”

“I’d be very interested to read it,” said Eden.

“Why?”

“I’m really curious to see what it’s like. I mean, maybe it’s great. I’ve been asking them to send it to me for months.”

“Why, because it keeps getting rejected? That’s a great reason to want to read something. It’s his first novel, and the only reason it’s handled by a top agent is because they represent his wife.”

A photogenic young poetaster approached us, or rather, approached Eden. A conversation sparked up between them on the subject of a mutual friend’s new book, and I receded quietly from the picture.

Despite professing to greatly enjoy everything he’d ever read by me, Eden hadn’t asked to see my novel, yet he could hardly wait to get his hands on the rejected novel by Emgona Merage’s husband, Suer Wightman, doubtless with a view toward publication… because it had been rejected by numerous other publishers. If rejection was such a mark of potential quality, why then not ask to read my novel? Because I hadn’t married well and I hadn’t been rejected by the right people. Eden seemed to care, but what he cared about was a matter of some concern. As I walked away, such tiresome considerations began to gnaw at my vitals.

All this stress and bitterness was the direct result of being involved, however marginally, in the literary world. If I didn’t write, then I wouldn’t have to complain about not being read. A little appreciation would, of course, go a long way towards improving my attitude.

Bill Traylor, Untitled, 1934. “John—I’ve read the excerpt you sent me, and I think in texture, sentence-by-sentence, it is often—generally—quite brilliant. There are sentences and small touches of (often splenetic and/or self-loathing) geniud scattered throughout, and the general precision of this voice is pretty extraordinary. The whole thing—this, and the rest of the book, depending on its nature and consistency and progress—may well be publishable. I do think that the overall misanthropy and self-flagelating may be too relentless for some readers. But I want to emphasize that the writing her, word- y-word, sentence-by-sentence, etc., is a really original and impressive achievement. Let me know whennyou think you’ve got the whole thung in shape, and I will do what I can to help you. As always, it was very good to hear from you.”

That was more like it. Within less than a week I had received a response from Jim Brooklinen. Jim had edited Elizabeth Hardwick and enjoyed weekly luncheons with Mailer in the seventies, so his response was tentatively validating. Failing eyesight could probably be blamed for the uncharacteristic litter of typos in his email, and he had somehow formed the impression that I’d sent him an extract from a work in progress rather than from a finished novel, but I could rectify that misunderstanding and offer to send him the entire manuscript. His response gave me a sorely needed lift.

“What have you been up to lately?” said Eden Gaperdiveve when I next ran into him.

“Just the usual round of bullshit. Nothing of substance, I can assure you. I’m still writing those articles.”

“That doesn’t take very long, does it?” said Eden.

“You’d be surprised,” I said. “The level of production may not seem justified considering the general indifference and lack of reward. It’s absurd on every level but…”

“Well, I’m enjoying them,” said Eden.

“You’re really going to enjoy the next one,” I said, somewhat sheepishly. I’d been wondering how to break it to Eden that I would be using him towards my own disreputable and self-serving ends.

“Why, am I in it?”

“Yeah, sorry about that. It’s not offensive. At least, I hope you won’t be offended by it…” I waffled on. Eden was an affable sort and I felt guilty about using him in this way, but he had furnished me with some rich material and I couldn’t seem to stop myself.

“Just as long as it’s not a hatchet job like with Tiffany Hardinskin,” he said, referring to the celebrated writer of ‘literary fiction’ that the Melinda Waterform character was loosely based on: a not entirely gratuitous slur on the over-revered.

“Don’t worry about that. You’re just a vehicle. There will be a few digs but it’s purely in the interest of moving the narrative along.”

“You hang around with writers, you’re going to get written about,” said Eden, shrugging it off. “I accept that.”

“Really, don’t worry about it,” I said. “Nobody’s reading it anyway.”

That was a relief. Eden didn’t seem to mind at all; he even seemed a little pleased about it. But he hadn’t read it yet.

This is Part VII of an on-going series. Please see previous installments: Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V and Part VI.

-

Publication in the Age of Negation, Part VI

An Old White Male, Inconveniently Still AliveWhy even catalog these grievances? I just wanted to get a book published. The documentation of this tedious process wasn’t something that could hold much interest for the average reader, whoever that was, or any reader, if there were any left.

I had wrongly assumed that Melinda Waterform would offer some sort of response to the manuscript that she had begrudgingly received from me, if only to avoid any awkwardness when we next encountered each other. She had certainly been friendly enough in the past. Still, I couldn’t really blame her for balking. Now that she was a famous author she was probably being subjected to constant pestering from every corner of the literary world. If the positions were reversed, I wouldn’t get back to her either… or would I? I thought about it for a moment: If a friendly acquaintance were to humbly force their work on me, regardless of the quality of the work or my feelings about the person, I would at least get back to them in a relatively timely manner and offer some sort of half-assed encouragement, however insincere. I had done it enough times.

I usually resented it when unsolicited manuscripts were dumped on me, especially by people I barely knew. It was a presumptuous imposition, and the experience was seldom rewarding. One was never really in the mood to spend three or four hours, or even twenty minutes, reading a virtual stranger’s work, especially on a computer screen.

My over-awareness of this familiar dynamic had tainted my recent exchange with Melinda, and now ruined any subsequent interaction. But I had only asked her to suggest a possible path towards publication, not to read the work—that had been her suggestion—and she had almost guaranteed that she would at least do that. Her reluctance was understandable. But if she read the work, she might…

So many mights, so many maybes.

Mike Eupole’s agent, Susan Fumus Blear, did not get back to me. Mike had probably told her not to feel under any obligation to respond to me, and explained, no doubt, that I was an importunate no-hoper towards whom ordinary courtesies need not be extended; and he probably didn’t bother to read the published works that I gave him either.

It is a great luxury to be secure in readership and remuneration. As well as providing a functional incentive to one’s endeavors it must also engender an added urgency and vitality to the process of composition itself, in the knowledge that one’s words are destined to be read: a sensation that is entirely foreign to me.

The novel possesses a certain vitality because I assumed, while writing it, in the back-to-front of my mind, that it would be published.

It is now unfathomable to me that I was able to entertain this illusion for years on end.

After taking so much care with this one work, and having made considerable sacrifices—financial, social, romantic—in order to prioritize it, only to experience the most unjust, indefensible and degrading forms of rejection, there is a danger of the potential vitality being prematurely drained from any subsequent literary undertakings.

Maybe the novel itself—I wouldn’t call it a book because it doesn’t exist in that form—has become stale from being left alone for too long. Could it not suffer the fate of all organic process and rot, and wither, before it has even seen the light of day? It is, in effect, an impotent work of art. For two years it has been left alone – occasionally, and with increasing infrequency, tinkered with, much like its author.

Time is running out, vital forces are in decline, there is no demand for the product I slowly but relentlessly grind out; yet I perversely persevere, grinding away in an overly familiar void, pressing on in the face of inevitable rejection, because I don’t know what else to do with the remaining time that is mine, and because it’s too late to stop now, despite the absence of any kind of reward.

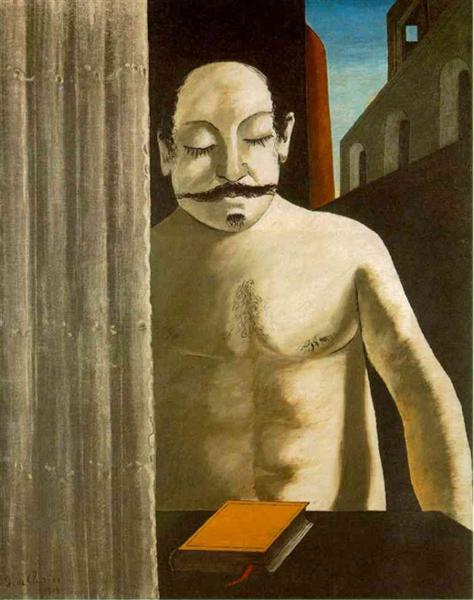

Giorgio de Chirico, The Child’s Brain, 1917. In the interest of further time-wasting and reveling in deeper irritation, I googled Melinda Waterform and found a recent article that lovingly chronicled her advancing friendship with Jose Mutha Clapshoe, a young writer of ‘transgressive autofiction’ that I had found, from my few brief forays into his work, to be as boring as he was popular; maybe I was missing something. Melinda had also recently written an in-depth profile of a famously underrated, glamorously tragic, manic-depressive Italian poet(ess) who had lately been receiving a lot of long overdue critical attention.

So there were writers that Melinda helped out… and their reputations were already secure. On the basis of what I’d seen of her articles, she liked to draw attention to her own taste by writing about already revered figures, the more romantic and difficult the better. She wasn’t, in effect, helping anybody; she was merely strategizing, establishing her own position in the canon alongside writers she wanted to be associated with… or so I thought to myself.

She was very careful about who she advocated for, and mine was not a cause she cared to be affiliated with: there was no reflected glory to be had there. Why boost the career of somebody that is truly unknown—an old white male, moreover; inconveniently still alive—when you can draw attention to your own taste by championing an already renowned figure who will afford you a certain gravitas by association, and thereby place yourself in that pantheon?

“I’ll do it because you’re a neighborhood character,” she had told me. That callous remark, with the implication that the work, were she to read the sample she’d asked me to send her, was secondary to my status as a “character,” gnawed at me, completely disregarding, as it did, the quality of the work itself.

Naturally, she hadn’t bothered to get back to me. I could sense her recoiling from the reflected shame that attaching her name in any way to mine could tarnish her with. If I was a fictional character, she might be more warmly disposed towards me. You read about such a person in a book and it makes you feel special to recognize their qualities, but you meet them in real life and you look down on them. As a real person, I didn’t cut it.

The self-pity was killing me.

Ramon Casas, Decadent Young Woman. After the Dance, 1899. All this stress and bitterness was the direct result of being involved, however marginally, in the literary world.

It was even beginning to interfere with my restorative walks, as there were now two renowned local authors to avoid, and be avoided by. I had noticed Mike Eupole crossing the street to avoid me on one recent evening, and suspected that he had altered the course of his neighborhood walks in order to bypass my apartment; while on my morning constitutionals I had to engage in stratagems of mutual avoidance with Melinda Waterform.

One summer morning Melinda crossed a leafy residential street directly in front of me, with a cellphone pressed to her ear and her leashed dog scampering and drooling alongside her. I stopped in my tracks and watched her pass by, with her dog’s proud asshole glistening in the soft early morning sunlight. I wasn’t sure if she’d seen me or not— she was so immersed in her phone conversation that she was probably oblivious to her surroundings—but it didn’t matter, as I was also avoiding her, partly in order to spare her the awkwardness of having to deal with me. It had now been several months since I had sent her my manuscript, and I regretted ever having approached her. The dynamic between us was so obvious, why not spell it out? You don’t read my work, so why shouldn’t I write about you? It’s not as if it’s very likely to be read, least of all by you.

Was this the best use of my depleting energies? Time was running out and all I could do was gripe about picayunities, rage against perceived slights, wallow in predictable regret.

My bitterness was beginning—continuing—to disgust me. The articulation of pettiness provided no satisfaction or cessation, and catharsis, if it even existed, which it didn’t seem to, was hardly sufficient justification for such a tireless outpouring of fribbling expatiations. Why not just ignore these ignoble thoughts, rather than carefully transcribing them?

This is Part VI of an ongoing series. Please see previous installments: Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV and Part V.

-

Publication in the Age of Negation, Part V

A Tiresome Outpouring of Fribbling ExpatiationsI don’t know how to create the impression of time passing. But it passed, weeks passed by, during which nothing much happened.

The sense of futility engendered by these dealings with the literary establishment hung over other potential undertakings. There didn’t seem to be much justification for this ongoing expenditure of waste, otherwise known as literary endeavor.

More than four years were spent writing a novel that remains unpublished. It’s unlikely that I will ever do anything better. I’m not getting any younger, and I may not even get much older. Under the circumstances there doesn’t seem to be much point in transcribing or describing anything anymore.

At this late stage of my brilliant non-career my chief motivation for engaging in this time-consuming and sadly only self-indulgent pursuit is to satisfy the insatiable demand for new material that will inevitably follow the runaway posthumous success of the novel in question, in the form of a slim companion piece. Although in my case posthumous success has become such an obvious irony that even that ice-cold compensation will probably be denied me.

Meanwhile, the Mark Eupoles and Jeff Dryers of this world churn out one book after another, secure in the knowledge that the slightest squirt from their golden pens will be preserved for posterity: a volume of adulterated juvenilia, a collection of essays on tennis, a miniature novella tastefully packaged as a single hardbound volume with embossed silver print on a black background and sold as an expensive signed limited edition. For these elite authors one undertaking automatically leads to another, with publishers always at the ready to distribute their latest wares to an eagerly awaiting public.

Appalled as I was by the prospect of using others to advance my cause, I was slowly being forced to arrive at the unpleasant conclusion that there was no other way. I couldn’t do it all on my own: I could produce the work but after that I didn’t know what to do with it.

Casting my mind around for influential acquaintances that might be willing to help, I lit on the prospect of my illustrious neighbor, Melinda Waterform, who had become something of an overnight literary sensation following the publication of her novel, The Habit Of Desire. She seemed to find me amusing but had never read my articles, despite my having urged her to do so, and despite our having reviewed, on several occasions, the same books—and despite my reviews being more entertaining and insightful than hers, which were now gathered in a collection published by one of the big houses, with a color photograph of her looking insufferably content on the dust jacket.

I frequently encountered Melinda when she was walking her dog around the neighborhood early in the morning, and sometimes we briefly chatted about her career. It would be opportunistic of me to approach her, especially as I had never read any of her novels. I couldn’t fathom what somebody who led such a seemingly idyllic existence—thriving career, financial security, happy family life, property owner, frequent travel, grants, residencies, ad nauseam—could have to write about. But writing wasn’t all about complaining, and from what I’d heard she was particularly skillful at fashioning compelling narratives out of calculatedly relevant contemporary subject matter. If her work was bad, it would annoy me. If it was good, it would annoy me even more, so I didn’t read it. But perhaps she might look kindly enough upon me to suggest an agent that I could hit up. After all, we were neighbors.

I balked at the prospect but steeled myself to gently petition her upon our next encounter, if she wasn’t already talking loudly on her cell phone, as was usually the case.

All disingenuous bellyaching aside, it wasn’t as if I was bombarding publishers and agents with multiple emails. If, as it has been said, one should put as much time into seeking publication as one does into writing the book itself, I was coming up short, very short. I hadn’t waged an intensive campaign to get this thing published; I had only made sporadic, half-assed attempts, and I had been too easily discouraged. It wasn’t in my nature to aggressively pursue publication, or anything else for that matter, and I needed my remaining diminishing reserves of energy for the work itself.

But perhaps this lack of effort resulted from an innate sense of hopelessness in the face of the crushing and chastening business of dealing with the publishing industry, especially in this day and age of strictly monitored content and preferential handling. There really didn’t seem to be any way in. Arriving unsolicited at a publisher’s door, you might as well be trying to sell them vacuum cleaners.

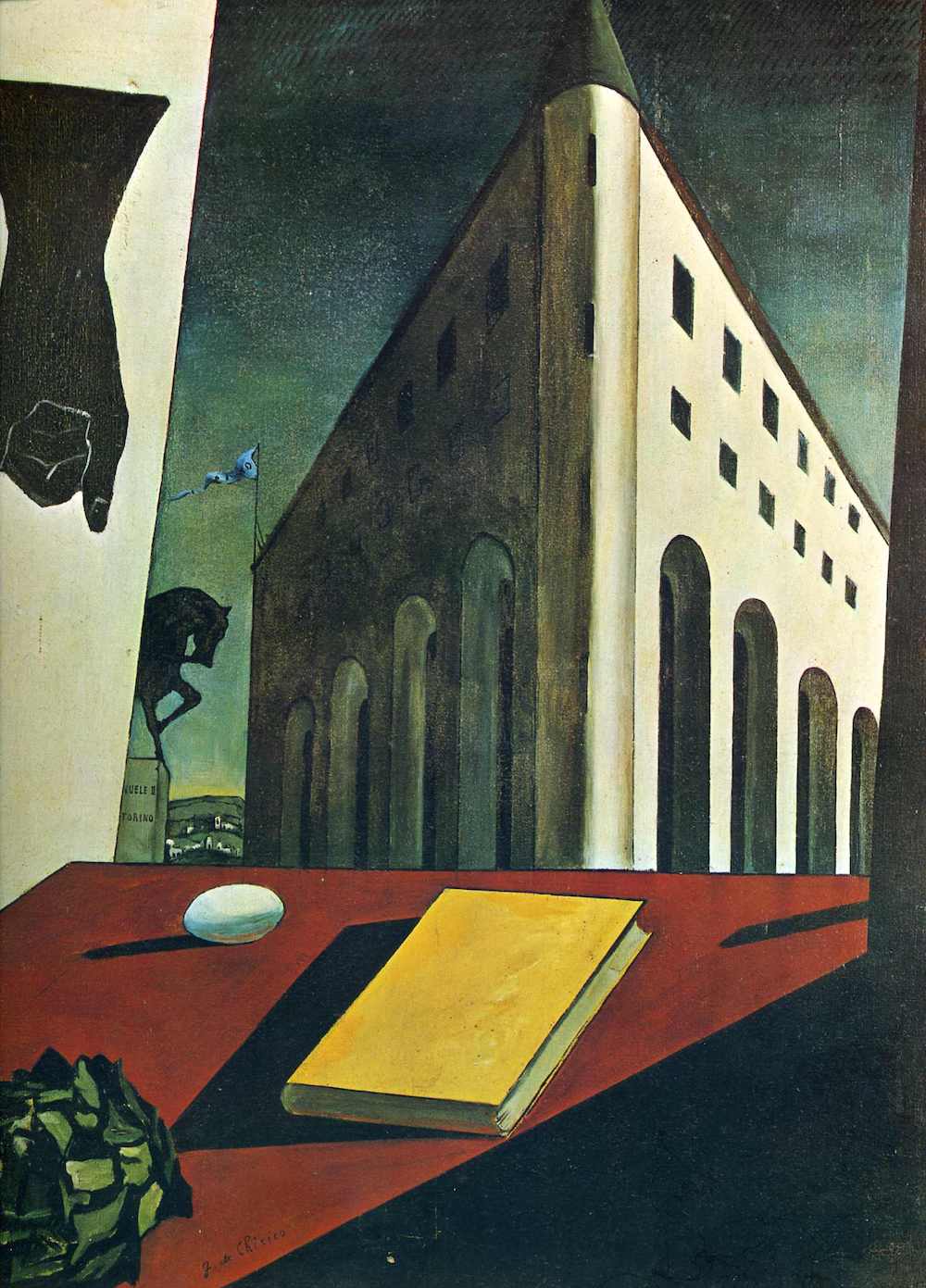

Giorgio de Chirico, Turin Spring, 1914. You might as well be trying to sell them fucking vacuum cleaners.

“Where’s your dog?” I asked, unable to come up with a better conversational gambit, when I encountered Melinda Waterform waiting at one of the interminable stoplights on Sunset Boulevard.

She put on a brave smile, bracing herself, no doubt, for an awkward and preferably brief exchange. “He’s at home with the children,” she said, sounding tired, and announcing the presence of something she had in her life that I lacked, and didn’t want.

“On the subject of dogs,” I said, “you should read my recent article on the subject in Artillery.”

“Oh, really?” she said, with a show of curiosity that sounded a lot like disinterest. “Do you have something against dogs?”

“I have something against noise,” I said. “It’s more about dog owners than dogs. It was inspired by an encounter with an arrogant dog owner in the neighborhood… not that all dog owners are arrogant,” I quickly added. Talking to Melinda had never been easy and now that I was going to be asking her for a favor, everything I said to her sputtered forth more clumsily than ever.

“I’ll read it,” she said, glancing anxiously at the unchanging Don’t Walk signal on the other side of the busy street. “How are you otherwise, doing good?” she asked, probably not expecting an answer, least of all a sincere one, as she pressed the Walk button.

“You know I wrote a novel,” I said.

“No, I didn’t know that,” she said, with a strenuously patient half-smile, as the countdown on the Walk signal began to flicker.

“Well, it’s not exactly common knowledge, but I did, and now I’m trying to get it published, and…”

The words came out flat and foredoomed, lacking conviction in the awareness of their ultimate futility. The Walk signal lit up, but Melinda raised her eyebrows and paid me the honor of waiting the light out.

“… do you know of any agents or publishers that might perhaps take an interest?”

“Well…” I watched her weighing the situation, with the overloaded scales tilting heavily against the desired response: “… I suppose I might have some ideas.”

The traffic continued to pour by. After a long ten seconds, she fixed me with her exophthalmic and Listerine-colored eyes and spoke very directly: “I’ll tell you what, I wouldn’t normally do this, but I’ll do it because you’re a neighborhood character. Send me a PDF. No, send a couple of chapters or whatever.”

“How about the first fifty pages.”

“That’s fine,” she said.

“Tonight, yes, I’ll send it over. Thanks.”

The Walk signal lit up again, and this time Melinda didn’t linger.

John Currin, untitled. As I walked away, I suddenly felt very small, my obscure position thrown into harsh relief. My hopes were raised, but it was not a pure sort of hope; it felt tainted and fleeting. Melinda’s disinclination had been palpable. She had no idea as to whether my writing possessed any merit, and didn’t seem interested in finding out. She assumed, I assumed, that owing to my age, social standing, and lowly station in life, that she had nothing to gain from bothering with it. And she had her own work to do: I understood that.

Nevertheless, I spent the evening editing a few passages together for her delectation. I harbored grave reservations about sending the work, or any portion thereof, to Melinda. She would now be privy to the contents, and could freely blurt about them to other literary friends of hers, perhaps in a disparaging manner; she could steal my ideas—she seemed like something of a literary magpie—or give them to someone else. She could also completely ignore it. None of these options were very appealing, but there was also the slim chance that she might be impressed enough to help me secure the services of an agent, although this seemed the unlikeliest of all these possibilities.

I sent her a modified version of the first fifty pages.

This is Part V of an ongoing series. Please see previous installments: Part I, Part II, Part III. and Part IV.

-

Publication in the Age of Negation, Part IV

Wasted WordsOne sends out this precious, all too precious, closely guarded work to complete strangers: they might initially take an interest, but after being presented with the entire manuscript, they can’t be bothered to get back to you at all, not even with a brief cordial rejection note.

It makes one doubt the quality of the work.

I started to re-read the work that has been the cause of all this unpleasantness again, and after a few pages began to see it in a harsher light: It was too repetitive, too relentless, too tight.

Since I officially finished the novel, over a year ago, I had spent a lot of time tinkering with it. Every time I opened the document, I would be confronted with something that needed to be changed, and then something else, and hours on end would be spent making minor adjustments, many of which didn’t need to be made. These endless finishing touches were draining the life out of the work, and I wanted to avoid the airless quality that I disliked so much when I encountered it elsewhere. I needed to leave it alone. But with no end in sight regarding publication, it was difficult to resist fiddling around with it.

It pained me to consider that I had prioritized this finely-honed ego-driven mess over everything else. All the time I’d put into constructing paragraphs, sculpting sentences, and leaving no synonym unturned in exhaustive searches for le mot juste—all that manic manicuring couldn’t turn out to have been in vain. What would be useful would be the services of an editor invested enough in the work to insist on my removing about a quarter of it, with whom I would be delighted to collaborate, preferably with the promise of publication.

Why this craving to be published by a ‘reputable’ imprint? Any self-respecting author should ignore the major outlets as an act of principle, and I would normally adhere to that credo, as I had done until now, not that I had any choice in the matter, but it was my stubborn belief that the work in question, by its nature, required such validation. Were it to be published by a micro-press, the sentiments contained therein would appear even pettier than they already were. Inevitably, I would end up settling for less: that knowledge was built in.

Vincent van Gogh, “Still Life with Three Books,” 1887. I walked out into the refreshingly cool evening air, straight into the path of a neighbor, Mike Eupole, who was taking a walk.

He didn’t seem particularly displeased to see me and obligingly took out his earbuds when I hailed him.

“I was just thinking about you yesterday,” I said. “I was reading your blurb on the back of Zander Valvitcore’s novel. What did you really think of it? Be honest.”

“I liked it,” said Mike unconvincingly. “It was a good story. It had some nice touches.”

“But he can’t write, can he? He can’t construct a complete sentence. It’s nice that he’s trying, and you can see the effort he’s putting into it, but he can’t quite manage it. He’s a nice guy though. I know him vaguely.”

Mike smiled and nodded noncommittally.

“This sort of thing really shouldn’t be encouraged,” I continued. I hadn’t been outside all day and after sitting at my desk—and in my green armchair, and on the sofa, and lying on my bed—brooding ruinously for hours on end about various slights and injustices, without speaking to a single person, I now found myself in an unusually garrulous mood, needing to let off steam. “I mean, what’s with this Alt-lit crap? Do we really need an alternative to literature?”

Mike laughed. He didn’t write Alt-lit, but he had supported it by bestowing a complimentary blurb on Valvitcore’s execrable novel, Wasted, that was getting a lot of undeserved attention owing to the author’s busy presence on social media, networking abilities, aggressive affiliation with a pointless and transitory new literary trend, and the book’s calculatedly attention-grabbing cover design.

“It’s just an excuse for people who aren’t interested in writing properly,” I continued, warming with malice to the subject. “It allows illiterates to make their contribution; it allows people who want to call themselves writers to commit acts of unacceptable degradation on the English language.”

“I guess it’s a bit like punk rock,” said Mike: “people who can’t play an instrument forming bands.” From his more elevated position as an established writer, he could afford to be more forgiving, or indifferent.

“Exactly,” I said, “and it has a snowball effect in that it encourages people to get involved in something they have no experience in or aptitude for. But it’s a lot more fun listening to somebody with loads of youthful energy bashing out three chords than reading somebody that can’t construct a sentence struggling to express themselves.”

“It’s an internet phenomenon,” said Mike.

“Maybe I’m missing the point,” I said. “But in 20… or 10… or five years’ time, will any of these epoch-defining works of Alt-lit, autofiction and so-called transgressive literature stand the test of time? You don’t need to be aligning yourself with this crap.”

“What are you up to?” said Mike, changing the subject.

“As a matter of fact, I’m trying to get a novel published,” I said.

“That’s great,” said Mike, suddenly sounding vaguely enthusiastic, and probably hoping to get me off his back.

“Well, it would be great, if I could get it published. Now I’m writing a series of pieces chronicling my various frustrating interactions with publishers and agents. Stay there. This won’t take 30 seconds…”

I went back upstairs as quickly as possible given my debilitated condition and picked up my car keys. Conveniently enough, my car was parked directly in front of my apartment. I opened the trunk and handed Mike the latest issue of Artillery.

“Here’s the first installment of the series. I can’t stop churning this stuff out. No amount of rejection can stop me. Sickening, isn’t it?”

“I know how it is,” said Mike, with a dry smile. Yes, he knew. But he was also assured of publication, having had a string of novels published by a major house.

“At least you have an excuse,” I said. “You know that your work is going to see the light of day. That must be nice.”

“I guess so,” he said, and gave a nonchalant shrug. He was out of the trenches but perhaps he had moved on to another, more advanced sphere of struggling. Each of us had our own battles.

“What’s your agent situation?” I asked him, and why not? It wasn’t every evening that I walked outside and immediately encountered a widely published neighbor. There could be no harm in asking.

“I have one,” said Mike with deepening indifference.

“Well, they seem to have done good by you,” I said, and elicited another good-natured but apathetic shrug.

“You’re welcome to contact her,” said Mike, kindly saving me the trouble of asking.

“Most kind. You really wouldn’t mind? Because I will.”

I reopened the trunk of my car and handed over the latest issue of the Santa Monica Review, which contained a short story of mine. “Read this, so you can be assured your agent’s time isn’t being completely wasted,” I said.

Mike probably wouldn’t read it. He was a helpful sort, but, I suspected, fairly indiscriminately helpful. It didn’t matter. He had provided me with the name of his agent, and I would contact them.

I walked down to Sunset. There was a new restaurant down there that apparently made a great hamburger. But on the strength of their weak name and the nature of the clientele observable at the outdoor dining section, I had vowed never to grace their threshold. However, they now had a take-out window open for business, and I ordered a hamburger to go.

“We don’t take cash here.”

“I’m sorry.”

The tiny young woman in the window repeated the statement.

“You’re joking…” I began to splutter.

“I just work here,” she said, and had to repeat this statement after another abortive eruption of spluttering indignation.

“For fuck’s sakes!… I know, it’s not your fault. Is there anybody here in a position of more authority that I can yell at?!”

There wasn’t. I walked off fuming about this elitist, self-defeating practice that discriminated against the poor, and those of us with bad credit. It wasn’t the only local dining establishment to have adopted this policy, which was illegal in New York. A cashless society: what was the world coming to?

Trophime Bigot, “A Doctor Examining Urine,” c. 17th century. I went ahead and contacted Mike Eupole’s agent, Susan Fumus Blear:

Mike Eupole might have warned you that I’d be in touch, as he was kind enough to pass your contact info along.

Yes, he probably had warned her. He had probably apologized in advance for the inconvenience of having to deal with me and told her not to feel under any such obligation.

The novel in question does not examine issues of gender, race, class or identity. However, encouraged by some positive recent developments (an outright lie) I’m renewing my efforts to get it published by a reputable imprint; at the very least, a good independent press with distribution. I am deluded enough to believe that the novel possesses sales potential… ad bloody nauseam…

The weeks passed by.

An encouraging rejection letter, if such a thing can be said to exist, arrived from the pen of Stella Loryn. It was evident that she, and her assistants, had actually read the thing, which was a new experience for me:

“I have shared your novel with several readers and each had great things to say about the quality of writing, characterization and humor: qualities that are intensified when delivered in such a unique and darkly humorous style as yours. The voice reminded me a little of Mitchell Wellbeck. I greatly enjoyed reading it, not least because you have managed to write unusually well about writing itself, which is one of the hardest things to write about.

However, as you are probably aware, the publishing industry is still impacted by several years of compromised business, and this has resulted in many established authors losing out, as well as debut writers. Even before the pandemic, dark and ambitious literary fiction was a tough sell, and with its effects still being felt, it has become even harder.

I have no doubt that there is a readership that will love your novel, and I would strongly advise you to continue submitting to other agents.

Again, we wish all the best for you and thank you for sharing this manuscript with us…”

There was a lot of sharing going on in the world these days.

More time passed by, as I knew it would, and I gave up, as I knew I would, on sending the novel out. The fear that I wouldn’t put the required effort into getting it published had quickly materialized. After years—decades—of self-thwarting procrastination, I had finally delivered of myself, but my efforts had failed to rouse much interest in the few incompatible parties I’d trafficked with. The sense of futility engendered by these dealings with the literary establishment hung over other potential undertakings. There didn’t seem to be much point to writing anymore.

This is Part III of an ongoing series. Please see previous installments: Part I, Part II and Part III.