Your cart is currently empty!

Tag: Christopher Hawthorne

-

Girl/AWOL, Interrupted – the continuing controversies; the classics revisited (1)

We don’t call it ‘AWOL’ for nothing, you know. So while you (and my editors) were all HOWLing for my updates last week – and oh yes, we did have a few – the local art world news was eclipsed by the Los Angeles Review of Books’ publication of Joseph Giovannini’s take-down (I almost want to say, tear-down) of the proposed/presumed Zumthor-Govan Gumby-blot LACMA-East, “Peter Zumthor at LACMA: A Preacher in the Wrong Church.” And if you thought Lane Barden and I were rough on Herr Zumthor, Michael Govan (and in my case, Christopher Hawthorne or for that matter A. Jerrold Perenchio), try exponentiating that by a factor of ten. I almost wonder now if Govan’s spirited defense at the Hawthorne/Occidental College initiated Third Los Angeles symposium last month was spurred not just by the disclosure of the ‘Gumby’ revisions to the plan, but in anticipation of Giovannini’s devastating critique which, in all probability, was already in progress. That slightly desperate edge now seems entirely warranted in the face of what Giovannini has unleashed. I’d be nervous, too, if I were in Govan’s shoes that night.

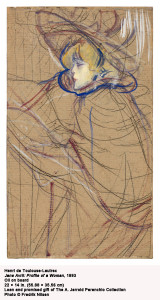

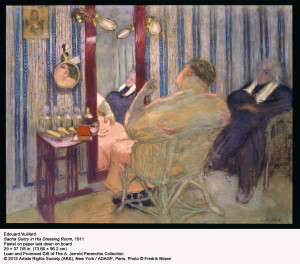

Govan was far from nervous at the media unveiling of the 50 for 50 presentation of promised gifts in honor of LACMA’s 50th anniversary, fresh from the trustees’ annual fundraising gala that raised some $5 million for the museum, and clearly elated by the breadth and quality of the bequests. And truth be told, there are some gems and one-of-a-kind masterpieces amongst this year’s gifts. There’s already been substantial coverage of the casta painting by Miguel Cabrera that will soon join the museum’s collection; but this was far from the only (or most) outstanding donation. A few of my favorites: a Toulouse-Lautrec portrait of Jane Avril like no other Lautrec I’ve ever seen – a performance unto itself in boldly sketched, slashed and swirled pencil or pen and brush strokes, with only the head in profile fully painted; Degas’ Café-Concert study in gouache, pastel and monotype was also unique; an extremely unusual Edouard Vuillard – atypical in its explicitly non-domestic setting of a theatrical dressing room, its very self-conscious sophistication – a backstage portrait of the great actor and playwright, Sacha Guitry. All of the foregoing (and more) among Perenchio’s promised gifts – and yes, they’re wonderful; but I’ll say it again: there’s no need to build a new museum (or even a wing) to house them.

Govan was far from nervous at the media unveiling of the 50 for 50 presentation of promised gifts in honor of LACMA’s 50th anniversary, fresh from the trustees’ annual fundraising gala that raised some $5 million for the museum, and clearly elated by the breadth and quality of the bequests. And truth be told, there are some gems and one-of-a-kind masterpieces amongst this year’s gifts. There’s already been substantial coverage of the casta painting by Miguel Cabrera that will soon join the museum’s collection; but this was far from the only (or most) outstanding donation. A few of my favorites: a Toulouse-Lautrec portrait of Jane Avril like no other Lautrec I’ve ever seen – a performance unto itself in boldly sketched, slashed and swirled pencil or pen and brush strokes, with only the head in profile fully painted; Degas’ Café-Concert study in gouache, pastel and monotype was also unique; an extremely unusual Edouard Vuillard – atypical in its explicitly non-domestic setting of a theatrical dressing room, its very self-conscious sophistication – a backstage portrait of the great actor and playwright, Sacha Guitry. All of the foregoing (and more) among Perenchio’s promised gifts – and yes, they’re wonderful; but I’ll say it again: there’s no need to build a new museum (or even a wing) to house them.

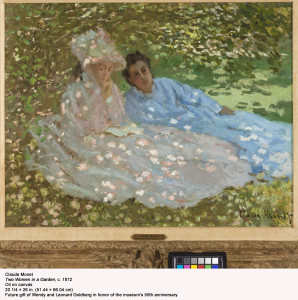

There were others: a breathtaking Monet masterpiece, Two Women In A Garden (from the Wendy & Leonard Goldberg collection) – a fabulous addition to the Museum’s collection; a very unusual (and great) Kirchner carved wood sculpture, a lovely Degas Dancer (also from Perenchio), an unusual Nolde portrait, a great Glenn Ligon, a great and unusual Warhol Two Marilyns (from the Nathansons); a Carpeaux plaster study that is sheer exuberant joie. Two of my favorite works were African tribal-spiritual pieces – one from Guinea, the other from a tribal (Kota) people that traverses Gabon and the Congo. The Kota piece was a double-sided object for veneration (in burnished wood, copper, brass, iron and shell) – the Janus Reliquary Guardian Figure – an object as magical as its reputed powers. The Guinea (Baga peoples) work was a tall sinuously curving prismatic Serpent Headdress (a-Mantsho-na-Tshol) in painted wood — as great as any Brancusi — that I hope Philip Treacy will be inspired to design a hat from. I kid (but maybe not) – but this is truly an inspirational, almost elemental form. The description that accompanied the work tells us that the spirit had an “ability to bring rain”; and we can only hope – from the serpent’s tongue to the goddess’s ears.

There were others: a breathtaking Monet masterpiece, Two Women In A Garden (from the Wendy & Leonard Goldberg collection) – a fabulous addition to the Museum’s collection; a very unusual (and great) Kirchner carved wood sculpture, a lovely Degas Dancer (also from Perenchio), an unusual Nolde portrait, a great Glenn Ligon, a great and unusual Warhol Two Marilyns (from the Nathansons); a Carpeaux plaster study that is sheer exuberant joie. Two of my favorite works were African tribal-spiritual pieces – one from Guinea, the other from a tribal (Kota) people that traverses Gabon and the Congo. The Kota piece was a double-sided object for veneration (in burnished wood, copper, brass, iron and shell) – the Janus Reliquary Guardian Figure – an object as magical as its reputed powers. The Guinea (Baga peoples) work was a tall sinuously curving prismatic Serpent Headdress (a-Mantsho-na-Tshol) in painted wood — as great as any Brancusi — that I hope Philip Treacy will be inspired to design a hat from. I kid (but maybe not) – but this is truly an inspirational, almost elemental form. The description that accompanied the work tells us that the spirit had an “ability to bring rain”; and we can only hope – from the serpent’s tongue to the goddess’s ears.

More to come, possums; stay tuned – ears to the ground, eyes to the skies….

-

‘That Transparency Thing’ – Blob to Blot, Part II – A Debate Over the New LACMA

[Part I of this post appeared yesterday, following the preceding evening’s Third Los Angeles forum at Occidental College. I continue where I left off – as LACMA’s Director, Michael Govan left the stage to the evening’s host, the forum’s principal organizer, and Los Angeles Times architecture critic, Christopher Hawthorne, and his panel – Alan Hess, Greg Goldin, Mark Lee and Sharon Johnston (of Johnston-Marklee), and Hawthorne’s L.A. Times colleague, Carolina Miranda.]There was something slightly awkward about this transition – as if an appellant advocate had made his argument, and the case handed over to a panel of judges to arbitrate or come to some definitive decision. It was a difficult case to argue and a difficult decision to make; and if the panel ultimately did come to some consensus, it was not exactly what we would call a clean precedent.

Govan had to defend what amounted to a quartet of contradictory positions. On one hand, he had to stand by the original design he’d gotten everyone worked up over to the tune of about $300 million. On the other, he had to defend the position that the changes made, though necessary and an improvement, had not fundamentally altered the original concept and silhouette for the building and site. Without going into detail about the alterations (which in any case are mostly covered in Hawthorne’s coverage), this is partially true and partially false. Although the altered silhouette has lost some of the spirit and sensuality of the original design, it is in some ways more coherent, the massing more equally (and gracefully) distributed to the north and south across Wilshire Boulevard.

The issue of ‘transparency’ was always a bit fraught, regardless of Govan, et al.’s initial hype, and for that matter regardless of hypothetical views into the galleries and perspectives onto the exterior; and Govan didn’t come close to making the case for it here. More problematic was the issue of the entrances, which were originally suppose to move visitors through the cylindrical glass columns or plinths, past storage racks of art, which would be at least partially visible to those outside. There were always issues with respect to access, preservation, movement/traffic and attendant structural stresses. But now the access points would be both reduced and more distantly placed. (And where exactly? And by what? That dreaded (by Govan, anyway) staircase? Zumthor and Govan appear not to have worked this out exactly.)

The axial shift of the museum’s Gumby-like footprint southward across Wilshire Boulevard could only strengthen the case for the elevation of the structure. But almost all the panelists expressed some concern for the (off-Wilshire) public space beneath the structure. The very fact that it would share the tunnel/channel it would create over Wilshire sets us up for a slightly darker – and less park-like experience than what might be expected or desired for a museum sited in what is, after all, a park; doubly ironic given that the Zumthor plan (in theory) returns two-plus acres to the Park.

That is to say, Hancock Park, whose original land concessions to the Museum, according to Greg Goldin, had been continually breached in its various expansions. In theory, the space would come in for much the same use as the Times Court between the Bing, Anderson, and Ahmanson buildings on the current campus. But, as Carolina Miranda, among others, suggested, the effect might seem a bit like hanging out under a freeway overpass. (Hawthorne noted that there were critics who saw the freeways as among L.A.’s greatest and most emblematic stuctures.) Not a big issue, assuming the light and space (and Park) only a few hundred feet away; but again, given the closure of those glass cylindrical supports, not exactly contributing to ‘transparency.’

Where Govan was most directly challenged (though not necessarily by the panelists individually) was the obvious (and clearly practical) shift from the flattened plot of galleries that filled the museum floor plan almost to its perimeter to a sectioned plan that gave some of the galleries double (and, from the appearance of some of the renderings, even triple or more) height. Govan’s original mandate had been for an aggressively flat, unbroken horizontal line; and Zumthor’s revised rendering had clearly breached that. There were no interior renderings to give an idea of the effect from inside the galleries, but the exterior effect was less than elegant. More to the point, the elevation no longer presented that unbroken horizontal line. Govan was insistent on a single storey museum that now had a dozen two- or even three-storey spaces. (I sort of wondered if this was the new de facto growth plan: just keep punching holes in the roof as needed.) Govan’s position now seemed all but absurd. My own guess is that this is a baseline cost issue. A second floor, however raw or partially finished, may add just enough expense to push the cost to a level the County Supervisors or certain Board members may find unacceptable.

Here’s the thing: the museum experience (as Alexandra Lange observed so eloquently) is not like other gallery, cultural or public/commercial/retail experiences. It is a place to muse, to wander, to browse speculatively. We’re not there to acquire or even experience something specific. There’s a certain randomness to the encounter, apprehending, observation that takes place in this setting. Alternatively, we’re there to look at something completely specific. Nothing is going to deter me from moving up to a second, fourth, or fiftieth floor, to see the exhibition I’ve come to see. (I was not so long ago on the 4th level of BCAM. Mr. Govan should be assured this was not a problem. This was a pleasure.) For that matter, I don’t buy it as commercial/retail psychology, either. If I’m at Barneys or Saks to look at Alaïa or Rick Owens, I’ll climb the stairs to get to whatever I’m shopping for. And then there are these things called elevators….

Alan Hess, an architect and Pereira scholar (he contributed to the anthology, Modernist Maverick: The Architecure of William L. Pereira), made a valiant case for preservation; but his argument devolved to historic/landmark terms: the historic synchrony and east-west symmetry of the Pereira art museum campus at Wilshire and Fairfax and the Welton Beckett-designed campus of the Music Center at First and Grand – both at the fifty-year mark. Miranda and others countered that there were quite a few notable Pereira buildings scattered throughout L.A. (e.g., the LAX Theme Building, CBS Television City) that had a stronger claim for preservation; and still others that would endure regardless of critical repute (e.g., the Variety Building right across the street, which Govan himself praised—not necessarily surprising given that half the LACMA administrative offices are in the building).

Sharon Johnston and Mark Lee, of Johnston-Marklee Architects, who certainly understand transparency, were thoughtful choices to fill the fourth and fifth chairs in the line-up. They’ve only recently designed a museum of their own (the Drawing Institute for the De Menil Collection); their architecture (the little I know of it) puts a kind of California, geometric spin on a post-Corbusier elegance. Both Johnston and Lee were, perhaps not surprisingly, inclined to give Zumthor a pass. (Mark Lee had a funny line about the Pereira LACMA, analogizing the Pereira oeuvre to Bobby Darin’s catalogue of hit pop songs, with the LACMA campus compared to a forgettable ‘B-side’ like “Splish-Splash.”) Johnston had an appreciation for Zumthor’s fluid tentative process and methodology, contrasting it with what she saw as a kind of presumptuous purchase on museum and site in the plan of Zumthor’s predecessor, Rem Koolhaas, who seemed to view the campus as “a totalized object,” as opposed to something that didn’t necessarily need to “reveal itself in an iconic way.” I sort of wondered what Govan might make of that, in that the Zumthor had and has a fairly well-defined, if not iconic, footprint that was probably one of its selling points.

Goldin in turn was eager to pull back the ‘footprint focus’ to the larger context of the place itself; concerned that, in ignoring the “political, cultural, historic process,” Zumthor was making a set of mistakes that paralleled Pereira’s own.

Miranda noted that she had just returned from Chile where she had an opportunity to see LACMA’s collection of Islamic art exhibited in the Santiago Museum’s expansive galleries – and how much better they had looked than in the smaller galleries and “dark halls” of the Ahmanson building. (Although not all the galleries are necessarily small in the Ahmanson, I was struck by her point walking down one such ‘dark hall’ just the other day, and into one of those smaller galleries (to look at the archival “Art and Technology at LACMA, 1967-1971” exhibit.) One thing everyone seemed to agree upon was that we’d all be happy to see the Hardy-Holzmann-Pfeiffer ‘wall’ ripped out as soon as possible.

When Hawthorne brought Govan back on stage for a wrap-up (and I thought – wrongly – audience questions), there was an almost palpable feeling of relief (even among those of us eager to toss him a few questions) – Hawthorne assuming a role that seemed a cross between the chair of a Ph.D. student’s thesis committee and Ryan Seacrest. ‘Well, Mr. Govan, you’ve passed our dissertation review and we’re happy to welcome you into the program.’ ‘So, Mr. Govan, how do you plan to juice up your next performance?’ Given Zumthor’s method, and the issues regarding transparency, gallery perspectives, visibility, Hawthorne gently raised the issue of possible “blind spots,” which Govan deftly turned to his agenda, even venturing (bravely, I thought) into the subject of the access/entrance/exit conundrum – with staircases.

“It’s not a big risk,” Govan confidently glided into seismic zones of controversy; “[Zumthor]’s already built two museums.” Then, hedging again: “It’s a worthy risk.” It might well be. But neither Goldin, nor anyone else had a chance to raise the political/financial/process/context questions Govan’s wager implicitly raised. Hawthorne might be excused for wrapping what was admittedly a long evening; but he clearly recognized the platform and privilege he had given to Govan. There’s also the question of access to this on-going process – a process that takes place largely behind closed doors between Govan and Zumthor exclusively. In Michael Govan’s world, $300 million is a mere bagatelle; even a billion won’t raise too many eyebrows. But a billion dollars is something to a city with a decaying infrastructure and where half the population struggles to pay its bills. For that matter, it was noteworthy that Hawthorne and the Los Angeles Times had been given such exclusive access to this story. Except for a postscript on Hawthorne’s piece that appeared on the Curbed L.A. site, there was no other coverage of the story. Hard to imagine The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, the Financial Times, and the Guardian blacked out – but there you are. I’m curious about this ‘bromance’ between Govan and Zumthor. Might there be any question of a ‘bromance’ between Govan and Hawthorne?

It may well be time for a new museum building; and allowing for a few qualifications, no one is really clinging to the Pereira campus. (And did we really need that Perenchio PR stunt? Is there anyone in Los Angeles who bought that charade?) The question is whether the Zumthor/Govan museum is that building (and whether we’ll even recognize it if and when it’s completed). In the meantime, we might try to stay focused on the art we plan on putting in it.

-

From Blob to Blot – A Debate Over the New LACMA

And so the Govan/Zumthor/LACMA PR juggernaut thunders on, steamrolling over those skeptical eyes looking over their shoulders from near and far, critics and other local scolds (and possibly its immediate neighbors), to say nothing of its own Board of Trustees, the Board of Supervisors of Los Angeles County and its 10 million citizens or for that matter the Museum’s own membership and core constituencies. Also niftily coopting the hometown press in the process by looping in the Los Angeles Times’ architecture critic, Christopher Hawthorne, a seemingly neutral third party, whose objectivity might be presumed (and trusted) by most of these parties—with the further validating presence of professional/critical colleagues and distinguished (and local) architects.

I’m not faulting Hawthorne either for his opinions or for giving Govan this forum. The forum – which was part of a series of forums, panels and lectures, dubbed (by Hawthorne himself) “Third Los Angeles,” intended to focus attention on the urban evolution of Los Angeles, and in particular what Hawthorne views as the third distinct epoch or stage in this evolution – had apparently been organized and scheduled long before this late March evening. I actually think I’ve learned more about Hawthorne the past couple days than either the LACMA Zumthor project, Michael Govan, or the urban evolution of Los Angeles – about which I have my own theories and opinions. Among other things I learned that in addition to being the Los Angeles Times chief architecture critic, Hawthorne is also a professor in the Urban & Environmental Policy Department of Occidental College (hence Occidental’s sponsorship of the series; KPCC-FM is also a sponsor). Whatever my reservations about his critiques and opinions, I can only applaud what he’s trying to do; I wish I had the time to audit one of his classes.

Whether further spurred on by yesterday’s L.A. Times’ coverage, which was based on reporting that included telephone interviews and extensive conversation with both Govan and Zumthor, or simply his own determination to head off potential scrutiny or hedge new criticism the ‘evolving’ structure might come in for, Govan took the podium like Rahm Emmanuel on the offensive for his municipal fiefdom. It was like an architecture history lecture on steroids – but then that might be a good description of the development of urban (and suburban) Los Angeles. I was grateful to have missed the first 10 minutes or so of this, both because most of this stuff is depressingly familiar to me, and again, I really don’t need to hear another specious gloss on this history.

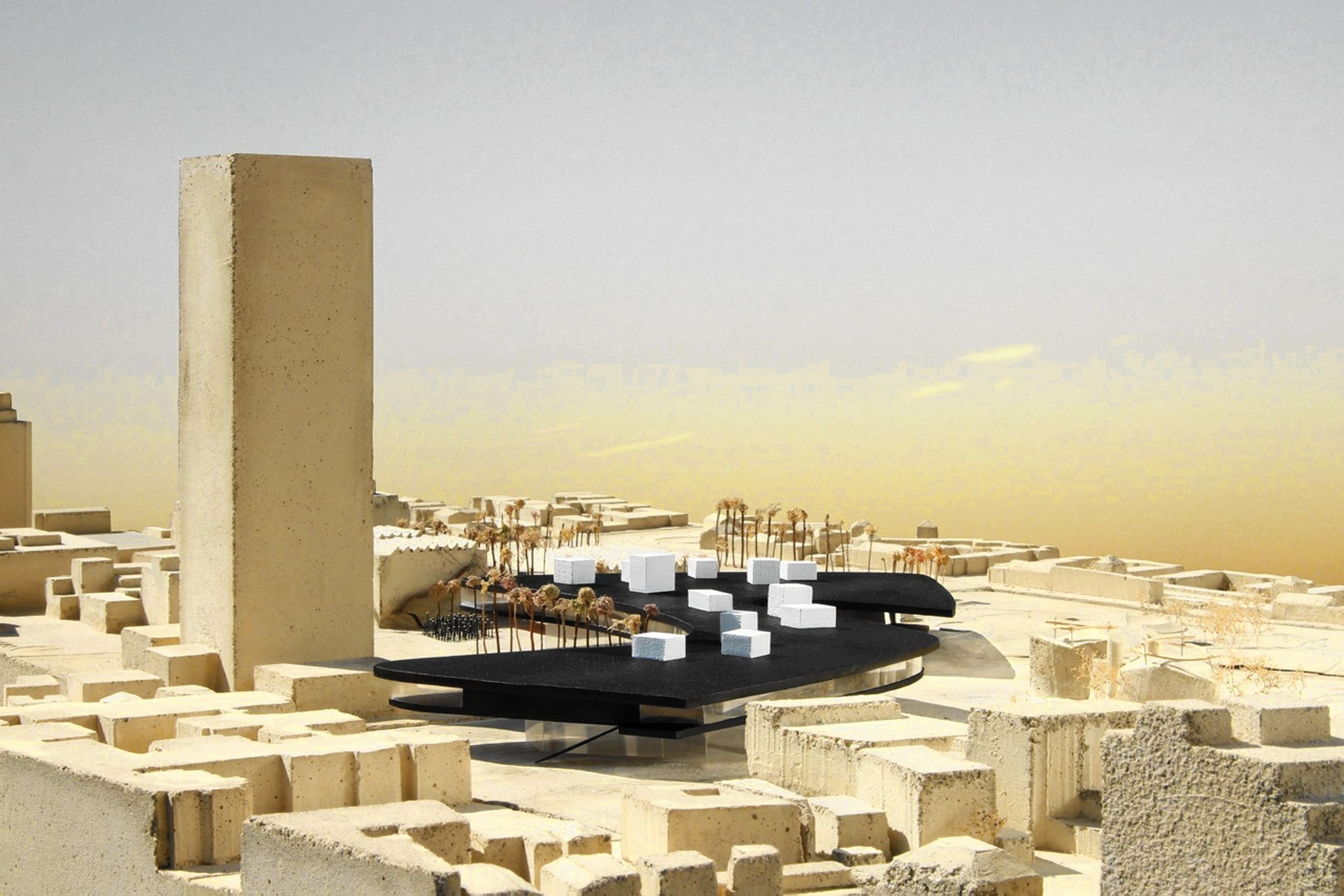

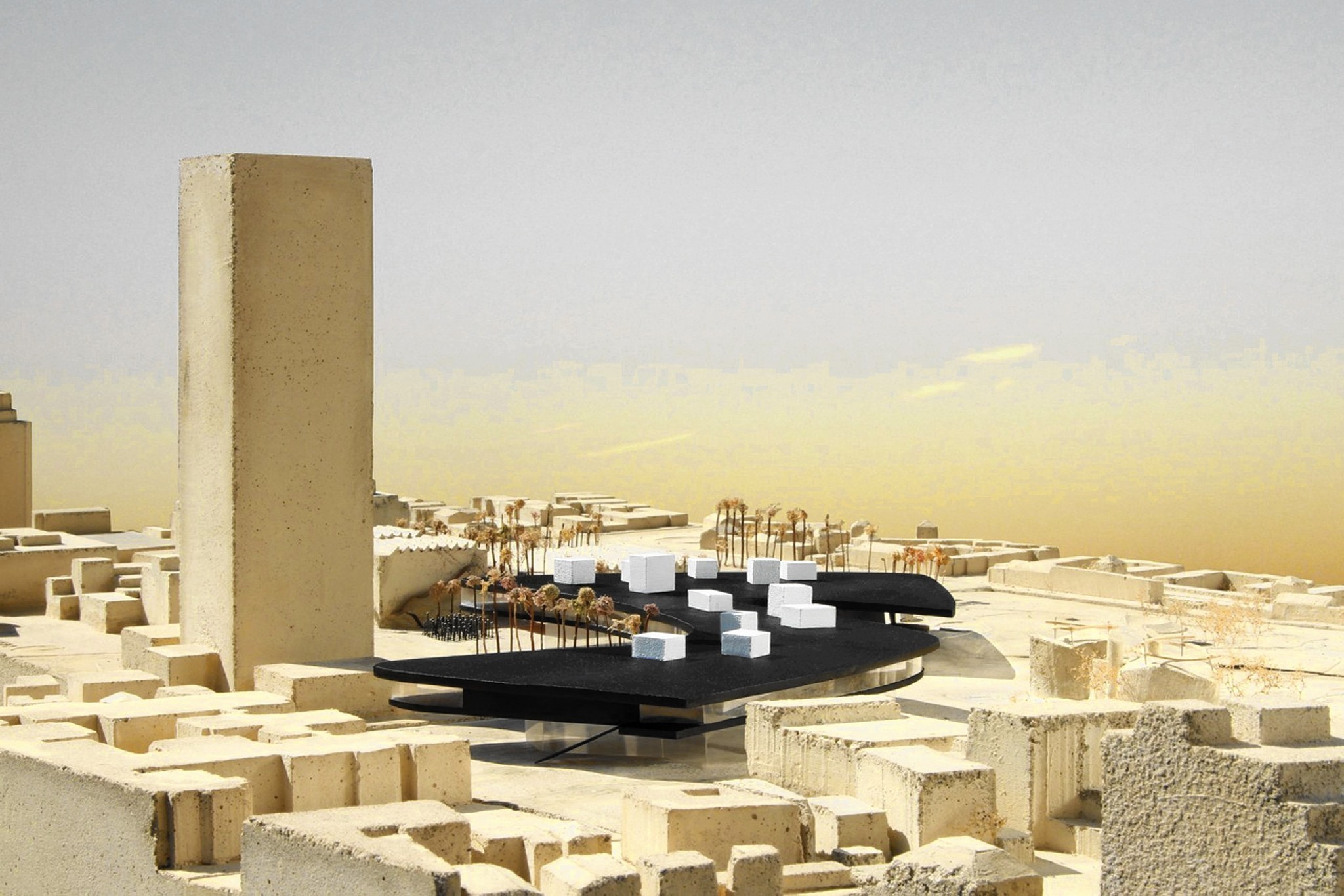

Govan then pivoted to his personal (after a fashion) architectural history – the projects he has had some role in overseeing or steering through public-private partnership (another buzz-phrase) to completion – e.g., MassMOCA and, that finest of architectural moments, the Guggenheim Bilbao. (Always nice to enjoy a moment in the sun before you jump into the black tar.) From there he moved on to address the original plan of the building and the proposed changes already sketched out in Hawthorne’s L.A. Times coverage in a kind of PowerPoint presentation: the elimination of public entrance through the plinths or support columnar elements that were once envisioned as visually accessible art storage units that the public might move through as they proceeded to the galleries, and consequent shift (and reduction) of the entrances to north, south and/or west sides of the structure; the reining in of the ‘blob’-like curvature into a slightly more trapezoidal massing pivoting westward towards the west side of the LACMA campus, curving in and over Wilshire, before fanning out (again somewhat squared off) eastward. In other words, the Googie shape is now more of a Gumby shape (not necessarily a tragedy, for those of us already inclined to be nostalgic about the original Zumthor blob) – perhaps with a little Richard Serra Tilted Arc thrown in (just so we know that it’s good for us). The interior plan continues to evolve: the interior ‘rat’s nest’ maze broken up and streamlined into six somewhat more coherent trapezoidal sections – alas pushed somewhat away from the circulation – the once mooted ‘verandah’ gallery – around the curvilinear perimeter of the structure; the dozen or so essentially white double-plus height galleries that will penetrate what was once viewed as an unbroken horizontal line; that and other possible variations to what was also originally visioned as a solid black (solar panel) roof and perimeter outline of the curving structure.

Throughout Govan stressed that this was not really a serious break with his original emphasis on the horizontal sprawl of the structure, returning again and again to the point, putatively borrowed from commercial consumer psychology, that visitors are decreasingly inclined to ascend to successive levels in multi-storey cultural (or commercial) facilities – conveniently ignoring the obvious fact that the structure as currently designed demands that visitors ascend to the first gallery level. (Always interesting how much attention is paid to such theoretical points, even as the actual effect is usually some reduction of movement or access – or choice – for the consumer.)

Given some of the remarks he’s made in the past, I have to wonder if Govan’s insistence on the one-floor/one-stop shopping scheme has as much to do with setting things up so he can build yet another ‘satellite’ museum somewhere else. (Last night he mentioned Inglewood – I hope he’s let the Metro transit people know where he wants the next subway line extension.)

He took some pains (or maybe the audience did) to emphasize that these changes reflected, not simply Zumthor’s and the museum’s respect for the La Brea tar pits and the public spaces around the Miracle Mile/Wilshire Boulevard location, but Zumthor’s consistent sensitivity to site. He also took note of Zumthor’s standard modus operandi – moving away from sketches or renderings to actual models and fitting the model with the site. The bottom line is that with Zumthor, you don’t know what you’re getting until you’ve gotten it – not necessarily a bad idea in theory, if you compare it, say, to a fashion designer working directly off the body of a fit model. The only difference is that a standing human body takes up two or three square feet. Here we’re talking about six acres of prime urban turf in the middle of L.A.’s Wilshire Boulevard, including infrastrucure. There can be unintended consequences. (I always wondered what the back story was on the planned museum in Berlin that actually broke ground but was demolished long before completion.)

It was all about the evolution of museums and public spaces. The changes go “on and on” at art museums, he stressed, again completely sidestepping his insistence that the changes stop at his piano nobile mono-level museum; all about – summing up again in bullet points – Transparency, Accessibility, Efficiency, and Sustainability. (In theory, there is a net return of energy to the city’s power grid from the all solar-powered zero-energy structure.)

After Govan had finished powering through this propaganda barrage, Hawthorne got back up on stage to probe tentatively at some of the main points and possibly ‘put a human face’ on them. He had put out the word on the forum to a few architecture/design colleagues some time before the panel/presentation to elicit comments and responses and he read from the commentary he received from design critic Alexandra Lange, which for me was the highlight of the evening, both as a critique of the ‘evolving’ ‘blob-to-blot’ structure, and an eloquent essay on the LACMA/museum experience and cultural experience generally – addressing aspects of the museum experience Govan’s presentation seemed to all but ignore. Lange’s commentary took the point of view of the casual observer, wandering in and out of doors through some of the landmarks of the site, the solitary art encounter framed by the sensual experience of the sights and sounds of the randomly (human) activated architectural space, its materials and atmospherics. Hawthorne then introduced the panel – his Los Angeles Times colleague, the seasoned art and architecture reporter, writer and critic, Carolina Miranda, architectural historian Alan Hess, long-time architecture critic and curator Greg Goldin, and architects Sharon Johnston and Mark Lee (of Johnston-Marklee) – which took the stage without Michael Govan, who then returned to his seat in the front row on the left side of the auditorium.

There was something slightly awkward about this transition – as if an appellant advocate had made his argument, and the case handed over to a panel of judges to arbitrate or come to some definitive decision. It was a difficult case to argue and a difficult decision to make; and if the panel ultimately did come to some consensus, it was not exactly what we would call a clean precedent….

[TO BE CONCLUDED IN THE NEXT POST]