Your cart is currently empty!

Tag: Chris Sharp Gallery

-

Michael E. Smith

at Chris Sharp GalleryMichael E. Smith’s unassuming, poetic sculptures are late capitalist Zen koans: riddles with no answer but which nevertheless spark a moment of satori. For instance, a milk carton covered in mirrors seems to suggest that we are all the lost children. But is this a joke or what? And to what end? The show-stopper is a large foam dice covered with actual bison scrotums. This might sound gimmicky but somehow isn’t. Despite their simplicity, none of these sculptures are easily reduced to a single obvious reading and offer something far more delicate: a collective invocation of absence, negation, and emptiness.

-

BEST IN SHOW: ARTILLERY 2023 TOP TEN

Breathless is not always an indication of on-coming medical crisis or pathology. Events (including cultural events) can stop us short or knock the wind out of us. And although the experience may be more common at live music events, it happens in galleries and museums, too. But at the close of 2023, the breathlessness we may have experienced intermittently in galleries blurs with a breathlessness we now encounter on an almost daily basis. The dark days of Fall 2023 are giving way to a spectral winter at the start of a political year where it seems as if the entire planet hangs in the balance.

Whether or not we saw this darkness specifically in work exhibited in L.A.’s galleries and museums, there was a great deal that reflected the bleak poetry of a planet and biosphere on the brink of catastrophe; a reflection of the earth’s generosity and a sense of irretrievable loss beneath it; the reflection of humankind confronting one another—alternately frightened, fascinated, and repulsed. In the meantime, L.A.’s galleries continue to burgeon and thrive. Galleries are now as strong as the artists they represent—reflected in the fact that some of the best shows of the year were group shows. The same might be said of its museums—and one show and one museum in particular. Closing out a year of stellar exhibitions, the Hammer Museum’s 2023 Made In L.A. biennial was perhaps its strongest ever. As Ann Philbin prepares to close out her tenure as Director, the L.A. contemporary art community owes her a tremendous debt of gratitude.

Max Hooper Schneider, Falling Angel (2023) Aircraft wreckage, fluorescent light tubes, Tesla coils, vintage neon signs, chains, crushed concrete, mixed media fiberglass pond, microcontroller, 156 x 99 x 162 inches (396.5 x 251.5 x 411.5 cm.). Courtesy François Ghebaly Gallery. Max Hooper Schneider — Falling Angels

François Ghebaly Gallery

May 6, – June 20, 2023Here’s a riddle: how many Lucifers does it take to crash a planet? The title carried a whiff of Milton’s Paradise Lost brimstone, and the exhibition’s drama fully measured up to it. The Lucifers crash, proliferate and burrow down into Schneider’s visionary lab and landscapes that many of us who have followed Schneider’s career over the last decade might have seen as nothing less than a promise fulfilled.

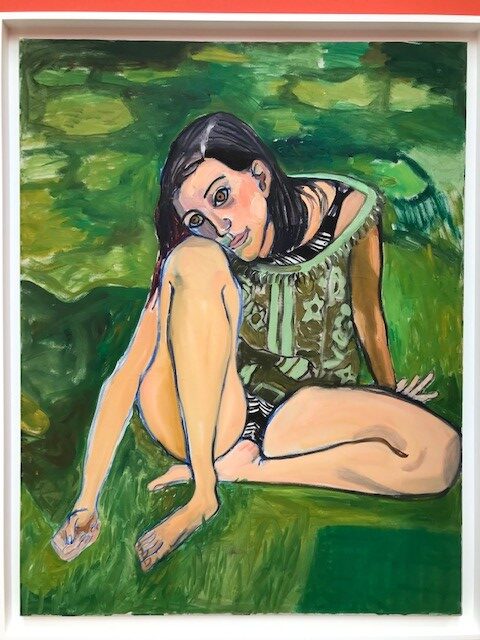

Alice Neel, Nancy Greene, c. 1965; oil on canvas, 47 1/2 x 37 3/8 x 2 inches (120.7 x 94.9 x 5.1 cm.) © Alice Neel, Courtesy BLUM. “Pictures Girls Make”: Portraitures — curated by Alison M. Gingeras

Blum & Poe (now BLUM)

July 2, – October 21, 2023A breathtakingly expansive survey of portraiture (from the mid-19th century to the present), Gingeras both recontextualized and redefined its domain in an exhibition that would have felt at home at the Met. “Portraits are pictures people make,” she declares definitively, embracing not simply the flux of personal, sexual, racial, ethnic or cultural identity, but an expanded notion of how this can be represented—entering not merely other worlds, but the shadow selves and lives within those worlds.

Martine Syms, The Fool, 2021; Laser-cut cardboard, Orafol vinyl with permanent adhesive and tape; digital video, color with sound, 4:11 min; 77.5 x 125.7 x 15.2 cm. © Martine Syms, Courtesy Sprüth Magers. Martine Syms — Loser Back Home

Sprüth Magers – Los Angeles

June 2, – August 26, 2023Given the timing, one could almost be excused for thinking Syms planned all along to pull the rug out from beneath what would become the summer’s blockbuster commercial film releases—which coincidentally navigated a similarly fraught domain of self, identity, and something that bore some resemblance to the ‘dysplacement’—the geography of self, its skewed nexus with place, and their continuous decoding, deconstruction, and reconstruction at the heart of her sprawling exhibition. (Or rejection: we might well want to burn it all down). Whether fragile domicile, the skin we inhabit, or merely the point our games come full circle—Syms’ ‘home’ is never less unsettling than the world erupting around it.

Mai-Thu Perret, She escapes the diamond pitfall and eats up the prickly thorns (2022) glazed ceramic (18 1/2 x 16 x 3 1/4 in. / 47 x 40.6 x 8.3 cm); courtesy David Kordansky Gallery. Mai-Thu Perret — Mother Sky

David Kordansky Gallery

March 18, – April 22, 2023Perret has worked in a variety of media over the years, but her affinities for ceramics have come to the fore in recent years, most recently in a residency at the CSULB Center for Contemporary Ceramics, which yielded the expansive circular wall piece at the center of this show—simultaneously a mapping (interior as well as exterior), landscape, and exegetically expressive exorcism. However central to Perret’s ‘sheltering sky’ vision, this title work could not eclipse other works in the show which evinced a similar visionary genius. Words cannot touch it, thought cannot reach it (her haiku-like title for a 2022 work)—yet somehow Perret did just that.

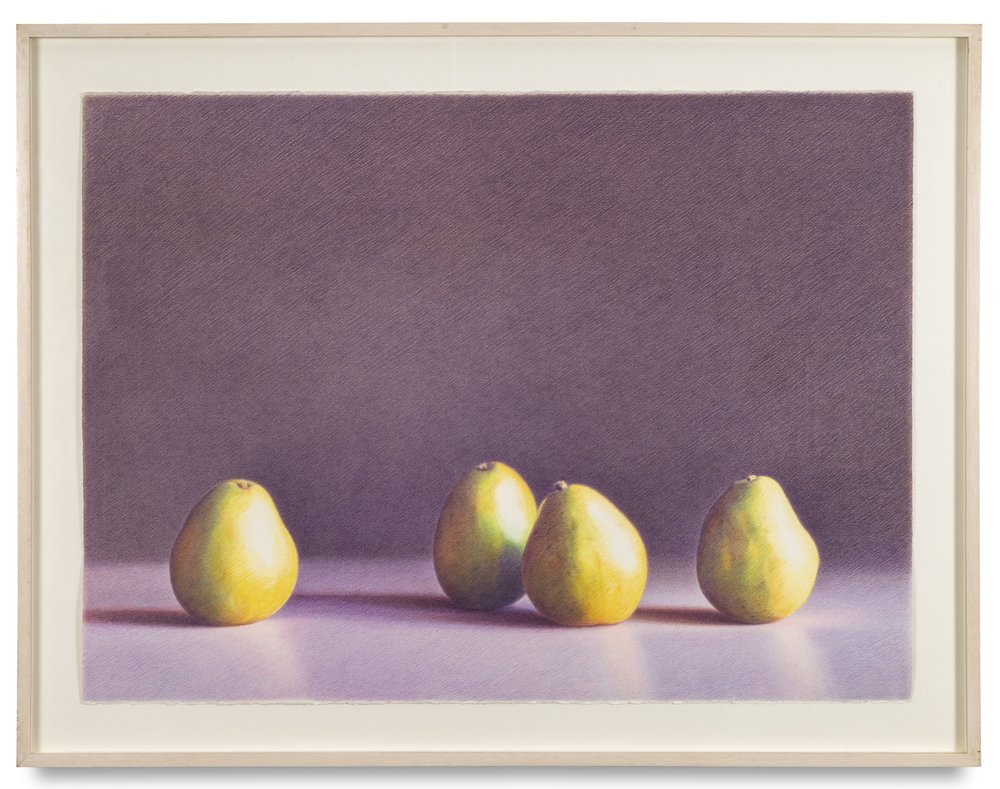

Martha Alf, Four Pears (1989) Verithin colored pencil on paper (22-1/4 x 30 in.) Courtesy Michael Kohn Gallery. Martha Alf: Opposites and Contradictions

Michael Kohn Gallery

June 24, – August 26, 2023Alf summarized her approach and intention: “It is about the perfection of the banal and the seriousness of the ridiculous.” This show was that and a whole lot more—really a phenomenology of perception and intention, variously influenced by Minimalism, Pop, and Fluxus, but unique and far more rigorous. She tested spatial and perceptual relationships to their limits and made magic of them. This superbly curated exhibition was nothing less than a poetics of perception.

Installation view, Barbara T. Smith: Proof, ICA-LA” at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles.

The Way to Be, performed at various locations between San Francisco and Seattle, 1972. “Barbara T. Smith: The Way to Be” at The Getty. Barbara T. Smith: Proof

Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

October 7, 2023 – January 14, 2024Barbara T. Smith: The Way to Be

The Getty [Getty Research Institute] February 28, – July 16, 2023The personal is both political and cultural—need proof? Really two shows, taken in conjunction with the Getty Research Institute’s extensive archive of Smith’s documentation, Xerox art and books (or “Coffins”), photographs, objects and memorabilia, Proof, alongside The Way to Be (originally a peripatetic performance repeated in locations between San Francisco and Seattle in 1972 and now the title of her memoir), is effectively a reconstruction of the scaffolding of an artist’s life. Born out of curiosity and inquiry, the feminist second wave, Fluxus, and the frustrations of a one-time suburban homemaker in a broken relationship (a story that could be a template for Six Feet Under’s Ruth Conroy), Barbara T. Smith wrote her second, third, fourth and final acts on her body (almost literally), pioneering performance art, and assembling a body of work to stand alongside a pantheon of her peers.

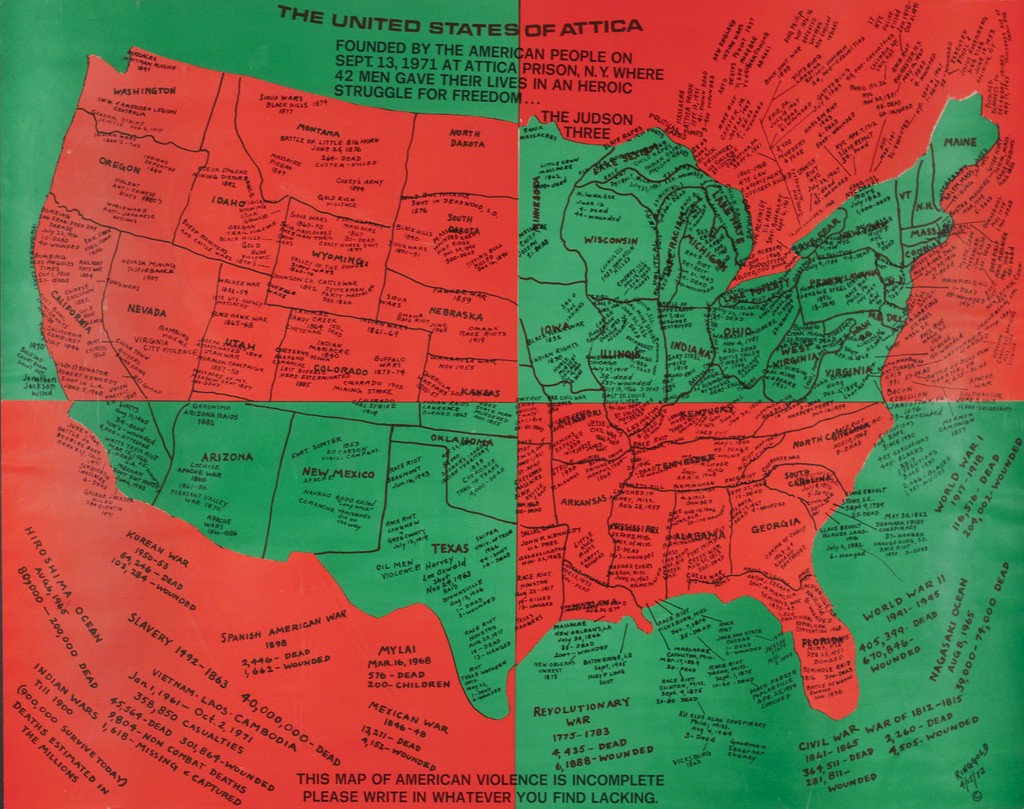

Faith Ringgold, The United States of Attica (1972) offset litho. (21 5/8 × 27 3/8 in. / 55 × 69.6 cm). Faith Ringgold: A Survey

Jeffrey Deitch – Los Angeles

May 20, – August 19, 2023Summer isn’t exactly the season it used to be, and aside from being an ‘off-season’ for the commercial art world, our calendars are as likely to be taken up with disaster preparation as vacations. Deitch’s concise but surprisingly comprehensive survey—the first in L.A.—of Faith Ringgold’s ground-breaking work—an authentic protest art at its best and most impactful—was the perfect corrective, distilling the last decades’ human social and political disasters, and simultaneously dissolving distinctions between art and craft into story-telling and perhaps a kind of prayer—anticipating the disasters just around the corner.

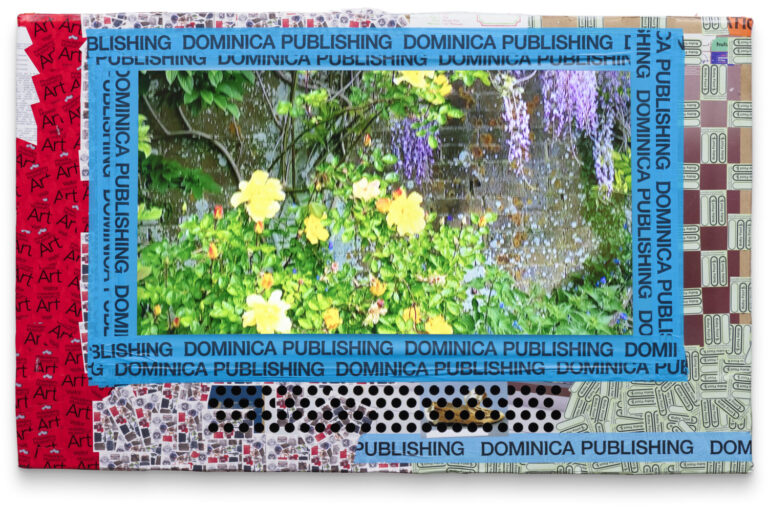

Dike Blair, Untitled, 2020, oil on aluminum (18 x 24 in.; 45.7 x 61.cm.) Courtesy KARMA Los Angeles Dike Blair

KARMA – Los Angeles

September 16, – November 4, 2023Dike Blair’s uncannily recomposed photo snapshots rendered in various pigments and supports (in this show, mostly oil on aluminum) remind us of something about the way life actually unfolds, how we remember it, and how we piece it back together. It’s a flash that’s a shadow—or that we might be a little too comfortable relegating to the shadows. It’s about moments and pictures that don’t necessarily tell a story—the interstitial, the in-between, but somehow indelible. This is an art of imagery that doesn’t flinch from banality, yet remains luminous, even incandescent.

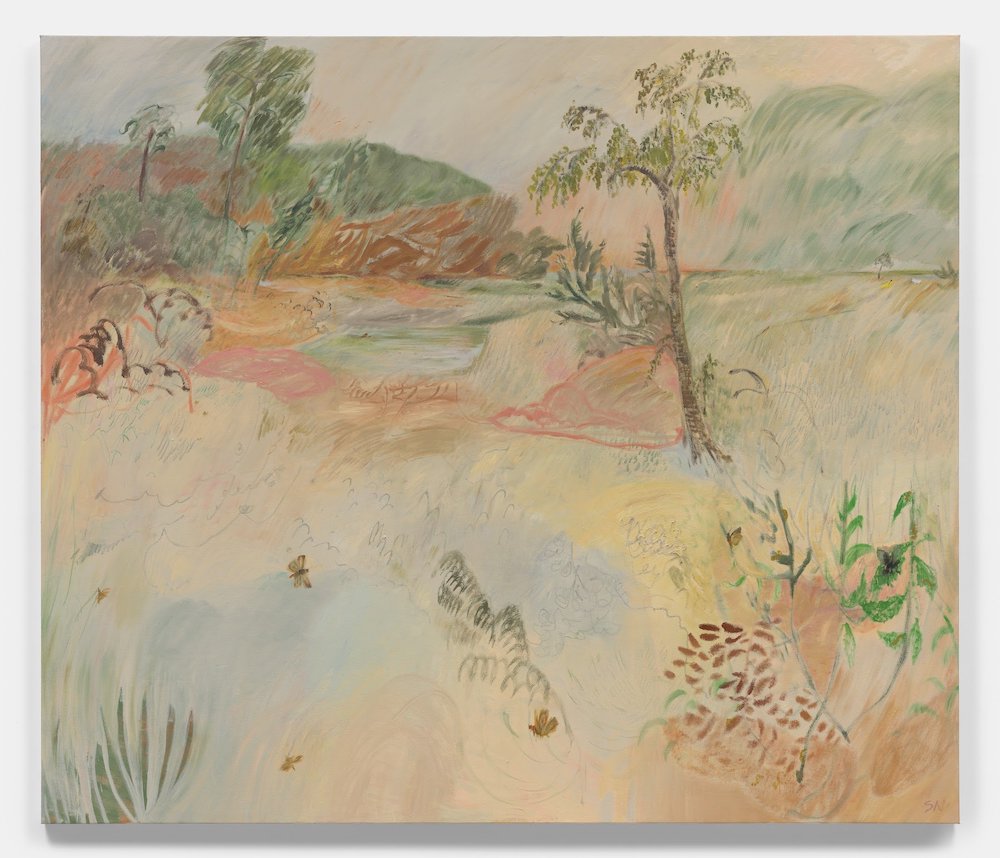

Soumya Netrabile, The Water Hole (2023); oil on canvas (72 x 86 in. / 182.9 x 218.4 cm.) Courtesy Anat Ebgi Soumya Netrabile: Between past and present / Between appearance and memory

Anat Ebgi – Wilshire Boulevard

September 16, – October 21, 2023We’re spoiled for great painting in Los Angeles of the 2020s, and for that reason we’re impelled toward making ever more expansive, almost capricious demands on it. But beyond the formal persuasion of the masterpiece that will not be denied is the delight of being taken by surprise—which is what really keeps us coming back. Nor is it necessarily about something entirely new. (The shock of a recovered memory may be sufficient.) Netrabile has her finger precisely on this pulse—recovering a space, a landscape, its features and objects, but reconstructing it without inhibition; retracing steps, but also reinventing her trajectory through it—committing the memory to dream. That approach extended to her palette throughout this show, which recalled Post-Impressionists from Bonnard to early Matisse. Hard to imagine recovering that mythic ‘bonheur de vivre’ anytime soon, but it was alive in this show—and (no doubt) Netrabile’s imagination.

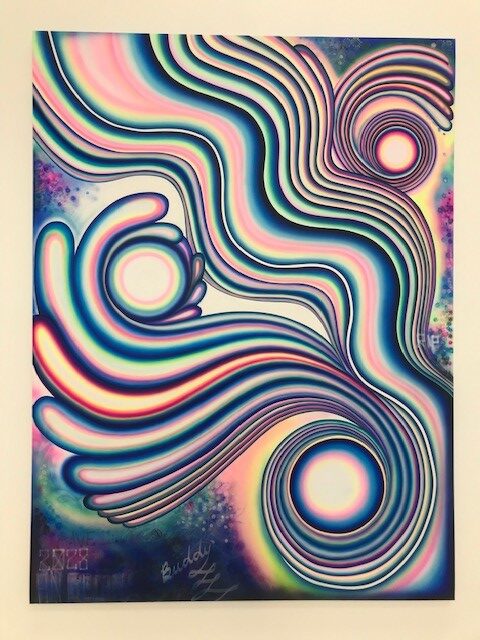

Angeline Rivas, Temporal Narcosis (2023) Acrylic on canvas (36 x 48 in. / 91.44 x 121.92 cm.) Courtesy Chris Sharp Gallery. Angeline Rivas — MKUltramarine

Chris Sharp Gallery

June 24 – July 29, 2023The intersection of memory and magic (or at least its invocation) is a complicated, even treacherous domain. I never saw the Joseph Sorrentino film, MK Ultra (2022—although Rivas’s show prompted me to look it up on-line), but I’ve read Philip Agee and listened to a lot of Frank Zappa’s music, which will probably suffice. With airbrush and fluorescent gradients of pinks, blues, greens, and all those colors you thought were liquid sunshine, but were actually just a grease puddle, Rivas channeled the visual dynamic of Kenny Scharf, the spirit of Judy Chicago, a Guimard-nouveau whiplash frenzy and that five-alarm fire where the transcendental gives way to sheer chaos in the most auspicious solo debut of the year.

-

Frieze LA 2023 — Flipping through my look book

This merry-go-round shows no sign of slowing down.Let me start by just getting a few things off my 28AA chest. I didn’t make it to ANY of the satellite Frieze Projects and am particularly upset about missing at least two of them—specifically Kelly Akashi’s project, Heirloom at the Villa Aurora (last week’s Pick of the Week), and W(hole), an intended partial exhibition or selection of works from what would become Julie Becker’s last body of work. (Although now that I think of it, it occurs to me that this particular exhibition might still be up—since it’s the one that’s actually on the Del Vaz Projects premises (Shirley Temple’s childhood home in Santa Monica).) The projects were curated by Jay Ezra Nayssan (Del Vaz is his own home-based curatorial project). It’s true that, in theory, I might have made it to one or two of them on my own. But seriously, given the number of art-related events scheduled that week, setting aside three full-blown fairs to go through, setting aside just … work … schedule … life…. (oh, and have I mentioned traffic? yeah….)—would it have killed you to keep them open for a month or so? The point being that Pacific Palisades and the Brentwood-adjacent portions of Santa Monica are not exactly within walking distance of the Santa Monica Airport. Or even biking distance. Or—under 2023 L.A. driving conditions—driving distance. (And not-so-incidentally would it kill you to invite your faithful correspondent to the media preview brunch next time?)

So the usual, not-so-usual, and a surprising number of never-usual-and-truly-extraordinary suspects (L.A. can be counted on to deliver in that last category) showed up, along with the usual on-lookers and troublemakers (myself included). And—this may sound funny for L.A.—but, whatever the minute-by-minute mood fluctuations through the fair, by and large we weren’t kidding around. (But then no one has time for that anymore.) Frieze was serious, too—this was by far the largest edition of the fair to hit Los Angeles, easily eclipsing ANY other art fair to ever hit the city—not at the scale of Frieze London (which also includes Frieze Masters), nor say, The Armory Show, but enough to justify return visits without becoming a blur (frankly a problem with those megalopolis convention center layouts). A lot of people in and around the so-called art world claim to dislike fairs, preferring to sample from their local (and/or New York and London) favorites and newbies, and dive in more or less randomly wherever their air miles accumulate and their carbon footprints start getting embarrassing. Art Basel can be intense; and Art Basel Miami Beach is—well, maybe closer to Animal Farm than a ‘zoo’, per se—truly an industrial enterprise. But I like magazines, and for me the best art fairs are like stand-up magazines where it’s the September, Holiday and Spring issues combined—fat with all the ads (always guaranteed to gladden a free-lancer’s heart). I wasn’t there to survey the attendees (have to assume Christine Messineo and her team are on that), but can safely say that amongst a random sampling of colleagues, collectors, artists and assorted pals and contacts, the impression was pretty favorable overall.

Christina Forer, “Regula ZH” (2021) This is not the usual buzz that comes back amongst media-ettes. But, as I said, no one was fooling around. It was impossible not to notice the prominent placement of the major L.A. galleries—but my focus was more on the, uh, “Focus” group of galleries that were featured in the Barker Hangar (which for this fair played back-up to the main WHY-designed pavilion). They included a number of younger L.A. galleries, including Chris Sharp, who showed Edgar Ramirez—whose work hardly needed to be singled out for acquisition by Santa Monica to stand out here. But there was quite a bit of strong work to go around—from Seoul (Johyun Gallery—with Lee Bae’s Issu du feu 8P (1998—though it looked startlingly contemporary) to Parrasch Heijnen, who, to my surprise, brought more L.A. Cool School classics (though still strikingly contemporary) than work more representative of their current artists and shows, which is just as strong. There was a lot of woven and textile work throughout the fair, and here the vivid and strikingly animated work of Christina Forer at Luhring Augustine stood out.

Arlene Shechet, “Together Again: Fall” (2022) In the main tent, the Kaiserin—Kim Dingle’s (deserved) honorific for her gallerist, Susanne Vielmetter, ‘won’ the L.A. contingent of the fair—simply by keeping the focus sharp and bringing the best, liveliest work—specifically, Nicola Tyson’s dreamy abstracted drawings—seemingly mapped out configurations of gesturing faces (or masks) and figures, and Arlene Shechet’s brilliant chromatic, vari-textured ceramic and steel sculptures—which might just as well be another life form. (Why not? With all the other life forms going extinct, we better dream up a few new ones.) I will say, I liked Maia Ruth Lee’s Bondage Baggage over at Ghebaly (has she been spying on me at airport baggage carousels?) and Kathleen Ryan’s cocktail garnishes (e.g., Bad Fruit (Tom Collins)—gorgeous—and genius).

Kathleen Ryan, Bad Fruit (Tom Collins), 2022 (with Maia Ruth Lee, “Bondage Baggage” in background While Kathleen Ryan has me thinking about maraschino cherries, lime wedges, and the two Sevillano Queen olives I insist upon in my (children’s size) Bombay Sapphire martini, let me take note of another distinction about this edition of Frieze L.A. (in very sharp contrast to last year’s Beverly Hilton romp): FOOD, glorious food. I was steeling myself for the worst. No—they still won’t comp you a glass of Champagne or an espresso, but here’s the thing: it was there, and it was relatively easy to get. And. Then. There. Was. Food. Thai food, pizza, panini, tacos, beverages—good quality and all reasonably priced. (Not the Champagne, though.) This is important because whether we realize it or not, after slogging through city traffic, the parking gauntlet (kill me now), or just street parking (which, if you had two functioning brain cells you figured out), and two or three hours straight of cruising and schmoozing, you are very likely dying of hunger.

Doron Langberg, “Sunflowers” (2022), courtesy the artist & Victoria Miro Gallery So let me cut to the chase right now and just say that Victoria Miro (London) won the fair. It’s one thing for a gallery’s featured (or ‘focus’) artist to make a splash with a signature installation or a suite of works that constitute a breakthrough transition. Certainly that happened here. But in addition to that artist—Doron Langberg—who commanded the space and eclipsed half of what was happening in the adjacent gallery spaces with his exuberant, rapturous painting, there was nothing on offer through the rest of the space that would not be prized, coveted, leave you breathless—from a genius Chris Ofili watercolour to a pair of Chantal Joffe portraits to another pair of Wangechi Mutu collages. Don’t make me go on because I’ll be sick—in the bad way that means the art was that good.

Doron Langberg may be new to me, but that means nothing. What’s hard to believe is not that I miss stuff (it’s impossible not to—and that’s a good thing); what’s odd is that even for us West-coasters, this Brooklyn-based artist has been quite visible for at least a couple of years. Which I would have known if my Times carrier (both Los Angeles and New York) had actually delivered my April 2021 T Magazine along with the rest of that Sunday’s New York Times (how’s that for a rant within a rant?—seriously it’s a problem), in which he was featured alongside another artist, Salman Toor. Most of my pals (and probably most ARTILLERY readers by now) are aware this is not necessarily the kind of work I’m readily drawn to. But why bother trying to categorize it as ‘figurative’ or ‘narrative’ or relegate it to one class of painting or another? I want to say his subject is life, actually—the ‘landscape’ of relations among living things within elastic, ever morphing spaces; and he addresses that subject as if he were conducting an orchestra. There’s a boldly chromatic and gestural quality to his painting that oxygenates even the most narrowly contained interior or exterior views. It’s work that can almost literally move you (and yes—that includes my brand of ironic laughter) or make you hold very still, register each note, breathe in and out on a long sustain. It’s music, it’s life—and right now, we’re all desperate to see more of that.

Fairs have a way of reflecting both the Zeitgeist and a kind of raw on-the-pulse sense of the way people are figuring it out and responding to it; and then, on a more commercial, transactional level, what draws us out of our little selves—and our wallets—and persuades us to part with some piece of that—really just our attention. It’s—‘come over here and have a look and maybe dance with this for a second.’ Yeah, look close, dive into it—or just bounce right off of it. You get pushed around a bit, but hey that can happen at Saks or the local Trader Joe’s. (Suddenly I’m reminded of a recent NPR news item about supermarket shopping as a date night. This is a date night where you don’t even need a date.)

A fair like this has a way of making us look at the way we live—in a culture, in nature, on this planet and in the cosmos; with each other as well as the art. We’re looking at art to conceivably live with, so we’re sort of quietly asking ourselves how we live at all. A great work of art has the power to change that dynamic. And you could see that going on from New York to L.A. to Tokyo to Seoul to Warsaw to Paris and back to London. Our relationship to nature and the urban environment and to each other were felt in work as diverse as that of Koichi Enomoto (at Taro Nasu, Tokyo)—flashback to a Neverland-innocent, almost sunlit (however artificially) moment, where one might conceivably allow one’s skin to freckle under a summer sky; Jean-Michel Othoniel (at Perrotin, Paris); Dana Schutz (at David Zwirner, New York), where pugnacious neighbors dare to draw their ‘red lines’ in sand or concrete; L.A.-based Christina Forrer (at Luhring Augustine, New York) whose figure’s expressive rage shoots colorful flames off her shoulders, displacing her head where her intestine should be; or the duo that calls themselves Peybak (Peyman Barabadi and Babak Alebrahim Dehkordi)—a glimpse of the apocalypse, from (brace yourself) Tehran (Dastan Gallery, Tehran), or Lee Bae, where the ‘fire’ has been reduced to actual charcoal (at Johyun Gallery, Seoul).

Doron Langberg, “Hibiscus” (2022), courtesy of the artist and Victoria Miro Gallery Then there’s the work that asks us what we’re becoming, who we really are anymore—as we’re continuously destroying, making over, maybe trying to save the planet and ourselves with it. The aforementioned Shechet and Tyson (at Vielmetter Los Angeles) were certainly all over that. So were a few of Ken Price’s classic pieces (e.g., Ghosted, 1998—at Parrasch Heijnen). I was not alone in noticing how much woven or textile work was dispersed throughout the fair in very disparate forms; also interestingly, frequently collaborative or collective work. I hesitate to read anything into this much less jump to conclusions. But rugs and tapestries were the original art of nomadic cultures; and as war and global migrations descend upon and sweep us up in their wake, we might all be reaching for something to connect us with our communities, whether dispersed or close-knit, and maybe a bit of comfort beneath the tempest.

-

GALLERY ROUNDS: Adam Higgins

Chris Sharp GallerySometime during one of those unremarkable post-Christmas pre-New Year’s days I was scrolling Instagram endlessly. In between sponsored health food ads, I came across an installation image of one Adam Higgins’ hyperreal salad paintings at Chris Sharp Gallery. My initial dismissal of the painting as simply more wellness content only furthered my fascination with the work. If I could be fooled into mistaking the painting for a photograph over Instagram, what was its effect in person? And why salad?

Upon finally visiting the exhibition, I was struck by how well the hyperrealism of the works holds up. The paintings are luscious and vibrant—like the crisp, green lettuce on a Big Mac in a McDonalds commercial. And, like a McDonalds commercial, the paintings invite you to come closer, to reach into the frame and take a bite. One painting in particular, Caesar salad with chicken and housefly (2022), held my gaze because of the impressive skill with which the weight and light of each leaf, crouton and cube of chicken were rendered. As I approached the canvas in an attempt to—I’m not sure what exactly, smell the work or touch it maybe—the realism of the painting disappeared into an intricate, dense field of short, blending brushstrokes.

Like the surprise that comes with actually eating McDonalds after seeing a much better-looking product in an ad, I became a victim of these trompe l’oeil paintings. Still stuck on my digital first impression of the paintings, I absentmindedly expected to see the veins of the leaves and the pepper in the Caesar dressing up close before being confronted with the actual construction of the painting itself. In this sense then, Higgins’ paintings are about painting, and he uses a strategic deployment of painting traditions to underscore so.

Adam Higgins, Caesar salad with gulf shrimp and red chard, 2022. Courtesy of Chris Sharp Gallery. Unlike the Pictures Generation painters who painted appropriated photographs, the salad paintings seem to be of subjects that are in the process of being photographed. For instance, the works Caesar salad with chicken and housefly, Caesar salad with gulf shrimp and red chard, and Caesar salad with pecorino romano lump (all 2022) include elements that seem to reflect a bright, direct light from above, as if the salads are artificially lit with studio lights. One can imagine the food stylists arranging shrimps just so and the lighting techs adjusting the studio lights to perfectly capture the full spectrum of color within the salads. In this way, the artifice of the entire endeavor is left intact. An artifice that is exaggerated once one recognizes that for the most part, the salads depicted are actually pretty gross—if not inedible—interspersed as they are with raw seafood, sweaty cheese, and uncooked chicken.

Though his paintings do belong in the still life tradition, Higgins differs by reorienting our perspective from that of the artist standing in front of their subject to a bird’s eye perspective looking down on it. With this new orientation, the paintings’ source of light becomes difficult to discern. The paintings’ overhead gaze emphasizes this artificiality, and the perspective recalls the countless “foodie” images buried on Instagram. “Phone eats first,” as the saying goes. Eating is deferred in the name of capturing an image of the food—a phenomenon that Higgins enacts through his use of trompe l’oeil. The viewer is beckoned towards a more fully sensuous experience of the paintings’ subject before finally, confronting the nature of painting itself. Higgins is able to utilize paintings’ formal history to wittily explore the cynical use of perpetually deferred desire in advertising and social media.

Adam Higgins: “My Salad Years”

On view through February 4, 2023

Chris Sharp Gallery -

Ten More to Remember — or simply bring to Los Angeles

Postscript to the 2021 Artillery Top TenAs I wrote to preface ARTILLERY’s 2021 “Top Ten” compilation, there could have easily been a parallel list of 10 or more shows and exhibitions approaching the level of the ten I selected. At one time, the magazine designated a few “honorable mentions,” usually, as I recall, footnoted in fine print. (There are only so many pages, after all; space limitations are a real thing.) This, too, was originally going to be appended to the “Top Ten” list; but after some discussion with my editor, it became clear this might not be quite enough—especially considering a number of important out-of-town shows that (especially in view of a ‘travel hesitancy’ no doubt corresponding to some extent with the far more pernicious ‘vaccine hesitancy’) demand to be brought to California.

Lynn Hershman Leeson, “Seduction” (1985) Lynn Hershman Leeson: Twisted

curated by Margot Norton

New Museum – New York

June 30, – October 3, 2021In some respects this slightly constricted retrospective brought Hershman Leeson’s work full circle—having presented Hershman’s Electronic Diaries as encoded into a strip of synthetic DNA, and personalized antibodies created in conjunction with the pharmaceutical company, Novartis. But I sometimes wonder if there is any way to do justice to the full scope of Hershman Leeson’s work without institutional commitment on the scale of an entire museum (possibly more than one institution). This is a plea to L.A.’s MOCA to commit the resources necessary to bring an expanded version of this show (see, the ZKM/Center for Art and Media’s Civic Radar) to the museum(s). If they need help, they might look up Amelia Jones (who led a terrific conversation with the artist by Zoom in conjunction with the exhibition) who may have an idea or two to move this forward—see that original Top Ten again.

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Electronic Diaries (1984-2019)

Alice Pelton, The Voice (1930) Another World: The Transcendental Painting Group

Group exhibition curated by Michael Duncan

(Emil Bisttram, Ed Garman, Robert Gribbroek, Raymond Jonson, Lawrence Harris, William Lumpkins, Agnes Pelton, Florence Miller Pierce, Horace Pierce, Dane Rudhyar, Stuart Walker)

Albuquerque Museum – Albuquerque, New Mexico

June 26, – September 26, 2021Fortunately, I don’t have to beg anyone to bring this show to L.A.—it lands at LACMA at the end of 2022 (to run well into 2023). The operative word here is transcendental—in both material and spiritual senses. The work here ranges loosely from the surreal and symbolist to biomorphic and geometric abstraction to non-objective painting, with some emphasis on a concept of light and space that seems borne out of the American Southwest—yet in its most outstanding examples distilled to a purity and intensity that seems illuminated to an astral dimension. Duncan’s brilliant show promises to make the L.A.’s next winter solstice the most radiant day of the year.

Clarence Holbrook Carter, “Following” (1973) Clarence Holbrook Carter – American Surrealist

Various Small Fires – Los Angeles

January 23, – February 27, 2021Readers will notice that there is something of a blur amongst several of these exhibitions (really almost all of them—but with particular emphasis to a radically transmuted or transformed and ultimately transcendent vision of physical and cosmic dimensions, of consciousness itself. Carter’s work seems to ‘land’ somewhere between Pelton and De Chirico—and birth and death—but with an intensity that could summon Lovecraft’s Cthulhu out of the cosmic void.

Make-Shift Future – installation view, Regen Projects Make-Shift Future

Group show curated by Elliott Hundley

(Kevin Beasley, Elaine Cameron-Weir, rafa esparza, Max Hooper Schneider, Eric N. Mack, Alicia Piller, Eric-Paul Riege, Kandis Williams)

Regen Projects

March 27, – May 22, 2021A truly spectacular show of masterpiece assemblage work by eight artists at the top of their game. ‘Every picture tells a story’ and each of these works deliver a world—“disquieting and uncanny situations” in Hundley’s words—looking to “massage loose the underpinnings of our attachments to contemporary mythologies … and reveal … so many blind spots.” They do—and ‘I can see clearly now….’

Ohan Breiding, installation view of ceramics and drawings (2020), from “Playing Submarine,” Ochi Projects Ohan [formerly Johanna] Breiding: Playing Submarine

Ochi Projects

February 6, – March 20, 2021Breiding’s work defies categorization both technically and conceptually—personal on an almost tactile level yet seemingly borne out of a collective unconscious, but all leading to a kind of personal confrontation with both self and community. They are an artist to watch.

Tom Allen, “The Song” (2021) Tom Allen: The Song

Chris Sharp Gallery

October 30, – December 4, 2021A spare show of five flower ‘portraits’—but they more than made good on the promise conveyed by the show’s title. The sheer chromatic vibrancy alone shook the gallery floor to ceiling in a range that went from schoolboy-treble to the Queen’s Throat. But beyond the chromatic effulgence, Allen cultivates and seems to pry something further from his captive specimens—a mystery or romance innate to the thing itself—taking the viewer (and conceivably the artist himself) by surprise.

Hans Holbein the Younger, “Lady with Squirrel and Starling” (portrait Anne Lovell?), oil on panel (ca.1526-28) Holbein: Capturing Character in the Renaissance

curated by Anne T. Woollett, Austėja Mackelaitė, and John T. McQuillen

Getty Center

October 19, 2021 – January 9, 2022Beyond the ‘flattening’ of history that seems an inevitable side effect of accelerating technological change, seismic social and political disruption, and environmental degradation, I was not surprised that this breathtaking exhibition drew so many contemporary artists here. Portraiture stops history short, faceting and dissecting character across culture and the electrically reactive skeins continuously woven between subject and artist. A ‘world-wide web’ indeed—and not so flat after all.

Alice Neel, “The Family” (John Gruen, Jane Wilson & Julia), oil on canvas (1970) Alice Neel: People Come First

curated by Kelly Baum and Randall Griffey

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

March 22, – August 1, 2021More portraiture, and even more irony—absurd to ask if the world needs it or why; we’re all (clearly) going there, and here’s why. People may or may not “come first.” (I disagree with Neel’s fundamental motivating principle.) But Neel connects with what connects us—whether (com)posed or seemingly caught between movements or a characteristic gesture, we see and hear the dialogue—questions, more than assertions, of ‘self’. It’s not who we are; it’s how we are. The painting provides us with an open-ended ‘why?’—and so there we are. (The show will travel to California this year, but not Los Angeles.)

Sonia Gomes: When the Sun Rises In Blue

Sonia Gomes: When the Sun Rises In Blue

Blum & Poe

November 6, – December 18, 2021As noted above, it’s hard to say whether ‘people come first’—but their stories can be compelling; and encountering this Brazilian artist’s work in an American exhibition space for the first time, it was astonishing to see and feel a powerful narrative sense wedded to a formal command of material and space that made me think of John Outterbridge’s assemblage work (also Senga Nengudi) as if distilled through the formal syntax of Anthony Caro. The materials—textiles and fabric remnants, driftwood, heirloom fragments—are collected close to home (she is based in São Paulo), but her meticulous workmanship and brilliantly composed and articulated form have a cumulative power that seems capable of transporting us to another dimension.

No—you didn’t miscount. There are only nine more here. But we’re already well into 2022—and did you really need any more?

-

GALLERY ROUNDS: Ishi Glinsky

Chris Sharp GalleryIshi Glinsky’s exhibition explores monuments of survival that honor the sacred practices of his tribe, the Tohono O’odham Nation, native to the Sonoran Desert in Arizona. Upon entering Chris Sharp Gallery I am instantly subsumed by Glinsky’s monolithically scaled leather jacket that levitates in the middle of the room. Coral vs. King Snake Jacket (2019) is colossally sublime, towering just over 10 feet tall. I feel an immediate desire to get close to the sculpture. I imagine crawling into the pocket of the worn-in jacket to discover an old receipt or a matchbox. The teeth of the zipper form interlocking arrowheads. Each crease in the leather recalls a story, a gesture, a history; each stud a piercing act of violence. As I look over each intricate detail, I notice that the jacket is adorned with an assortment of patches and pins, as leather jackets often are. Some are insignias for bands like Public Enemy and the Dead Kennedys, while others signify Native American activist groups, such as AIM (The American Indian Movement), and MMIW, stitched in black and red beads to represent missing and murdered Indigenous women. The sleeve of the jacket reads “YOSEMITE MEANS THOSE WHO KILL.” While the leather jacket’s hard exterior is a cultural symbol for rebellion, it also offers warmth and protection. Glinsky’s work embodies Indigenous history, resistance and survival.

Coral vs. King Snake Jacket, 2019 The radically oversized scale of Glinsky’s sculpture pays homage to Indigenous practices and native land that has historically been exploited and unrecognized. Western-hegemonic art history recalls monumental art by minimalist giants and land artists like Donald Judd and James Turrell, who have historically exploited stolen land, using it as a backdrop for their work. Art history works to reinforce violent colonialist narratives. We need new monuments and new storytellers. Glinsky’s sculpture acts as a counter monument that acknowledges and celebrates Indigenous people and their survival. While minimalism offers ahistorical universal ideals, Glinsky’s monument denounces dominance and claims resistance.

Coral vs. King Snake Jacket (detail), 2019 Indigenous scholar and activist Gerald Vizenor characterizes “survivance” as an active sense of native presence over absence, nihility, and victimry. Survivance carries forward Indigenous stories through collective memories and embodied practices.[1] Glinsky’s monument announces and honors Indigenous survival, demanding space for remembrance and existence.

Installation view: Friend ore Foe, 2021; Blue Rider, 2019 Chris Sharp Gallery

runs thru April 24, 2021

Sonia Gomes: When the Sun Rises In Blue

Sonia Gomes: When the Sun Rises In Blue