Your cart is currently empty!

Tag: black artist

-

Beautyful Migrations

The Diaspora According to Njideka Akunyili CrosbyNjideka Akunyili Crosby is having quite the year. Her figurative paintings are on the walls of esteemed museums and institutions across the country, often featuring portraits of herself, friends and family. Akunyili Crosby’s unique style consists of painted, drawn and collaged elements that she blends with a distinctive photo-transfer technique. She uses imagery sourced from magazines, catalogs and her own photographs.

Born in Enugu, Nigeria in 1983, Akunyili Crosby grew up between Enugu and Lagos, and moved to the US when she was 16. Now living in Los Angeles, she brings together these varied influences, seeking spaces where they diverge and intersect. Since earning her MFA from Yale in 2011, she has had exhibitions in major institutions nationally and abroad. She received the highly coveted MacArthur “Genius” Fellowship in 2017, and the United States Artists’ fellowship in 2021. Historic, cultural and diasporic references are at the core of her work. She touches on issues that speak to many different people, places and times, all elegantly woven together in layers of visually stunning imagery.

Akunyili Crosby tells personal and collective cross-cultural stories in paintings that are captivating and contemplative. In November 2021, the Metropolitan Museum of Art commissioned the artist to create a wallpaper that has become an exemplary case of how she addresses complex issues. Made for Before Yesterday We Could Fly: An Afrofuturist Period Room, she conceived of Thriving and Potential, Displaced (Again and Again and…) (2021) a gorgeous green vinyl backdrop. The Afrofuturist installation is one of the Met’s “period rooms,”—recreations of domestic spaces intended to be studied as representations of a specific time.

The Afrofuturist Room addresses the history of the land upon which the museum was built. Called Seneca Village, the area was home to a flourishing community of landowners and tenants who were mostly Black. The city seized the land in 1857 to create Central Park and displaced the residents. The new installation recognizes this history and imagines what a period room might look like if Seneca Village had remained. In doing so, the room shifts from the tradition of focusing on one specific time and celebrates the African and diasporic belief that the past, present and future are connected.

Embracing the layered history told through the installation, Akunyili Crosby’s wallpaper includes images of an archival map of Seneca Village from 1856, which are blended with 19th century photographs of Black New Yorkers, as well as contemporary African diasporic representations. Weaving through these images are verdant okra plants, a crop with significant history as it was carried along with enslaved people through the Middle Passage from Africa to America.

As is common with Akunyili Crosby’s large-scale installations, the wall-paper was originally created as a painting on paper. Previously unseen publicly, the painting is now included in the artist’s current solo exhibition at the Blanton Museum of Art in Austin, Texas. Just four works make up the show, all of which were made during the pandemic, giving a glimpse into the artist’s life at home in Los Angeles.

Dwellers: Native One, 2019 © Njideka Akunyili Crosby, courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro, and David Zwirner, Photographer: Jeff Mclane These new works underscore Akunyili Crosby’s interest in plants, including the aforementioned okra. Having studied biology in college and grown up with parents heavily involved in science and academics, she often features the natural environment in her work. In addition to the painting now adorning the Met’s wallpaper, the other three works in the Blanton show focus closely on plant species found both in Los Angeles and Lagos. The largest work is Still You Bloom in This Land of No Gardens (2020), a self-portrait holding her young child on a porch surrounded by plants. The artist looks straight at the viewer with calm, assured and loving eyes. Her child wears a shirt adorned with the words “black is beautiful.” The pair are a ideal representation of the relationship between mother and child.

Returning to her alma mater, Akunyili Crosby’s work will also be the subject of a solo show opening in September at Yale University’s Center for British Art. The exhibition is the third and final in a series curated by Pulitzer Prize–winning author Hilton Als. The show focuses on her ongoing series The Beautyful Ones, a reference to the debut novel of Ghanaian author Ayi Kwei Armah from 1968. Titled The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born, the novel follows a man as he navigates postcolonial Ghana in a formative period of unrest, loss and political awakening. The series, begun in 2012, features portraits of Nigerian children from her family photographs, as well as images she took on trips to Nigeria.

In addition to her work as an artist, Akunyili Crosby is a dedicated climate activist. She is a founding member of the Environmental Council at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, the first of its kind for a major art museum in the US. The council provides funds for the institution’s commitment to carbon negativity and carbon-free energy and supports exhibitions and educational programs that address climate, conservation and environmental justice.

In another large-scale installation, Akunyili Crosby showed her support of climate activism by contributing to the visual campaign A Cool Million. Founded by three artist-led collectives: For Freedoms, Art + Climate Action and Art into Acres. The campaign launched in April and turned pieces by leading artists into large-scale public works that were displayed on billboards and in museum spaces across California. The goal of the initiative was to raise climate awareness and funds for the conservation of one million acres of forest that is crucial to supporting the state’s hydrological system. Her work, Dwellers: Native One (2019), was transformed into a window vinyl for the Museum of the African Diaspora (MoAD) in San Francisco. The installation, on view through mid-September, features lush, dense plants indigenous to Nigeria layered with photographic transfers of the artist and her sister in their ancestral village, as well as an image of a woman advertising African wax-cloth fabric.

In January of 2023, Akunyili Crosby is set to kick off the exhibition program for David Zwirner’s new Los Angeles outpost. As LA begins to feature more of her work, she celebrates the similarities and differences between her African heritage and new home.

Visually stunning, captivating and laden with significance, she always tells complex, transnational stories and underscores the beauty of embracing multiple cultures.

See more of Akunyili Crosby’s work upcoming at Yales Center for British Art, then showing at The Huntington Feb 15-June 12, 2023.

Info: https://britishart.yale.edu/news-and-press/announcing-hilton-als-series-njideka-akunyili-crosby -

Racial Reckoning

Mark Steven Greenfield Illuminates the Black ExperienceIn 2020, Mark Steven Greenfield unveiled a new body of work, “Black Madonna,” followed by “HALO” in 2022, both at the William Turner Gallery in Santa Monica. Gallery owner William Turner told me in an email that the “Black Madonna” show was a natural progression of Greenfield’s career of investigations into race and racial identity. “It was a sensation when we opened it in the fall of 2020,” Turner says. “It was purely coincidental, but after the summer of George Floyd and Black Lives Matter, our show became a catalyst for people discussing these issues.” Turner witnessed viewers staying nearly an hour in the gallery studying Greenfield’s intricate paintings. “We have never had a show that had that kind of depth of impact.”

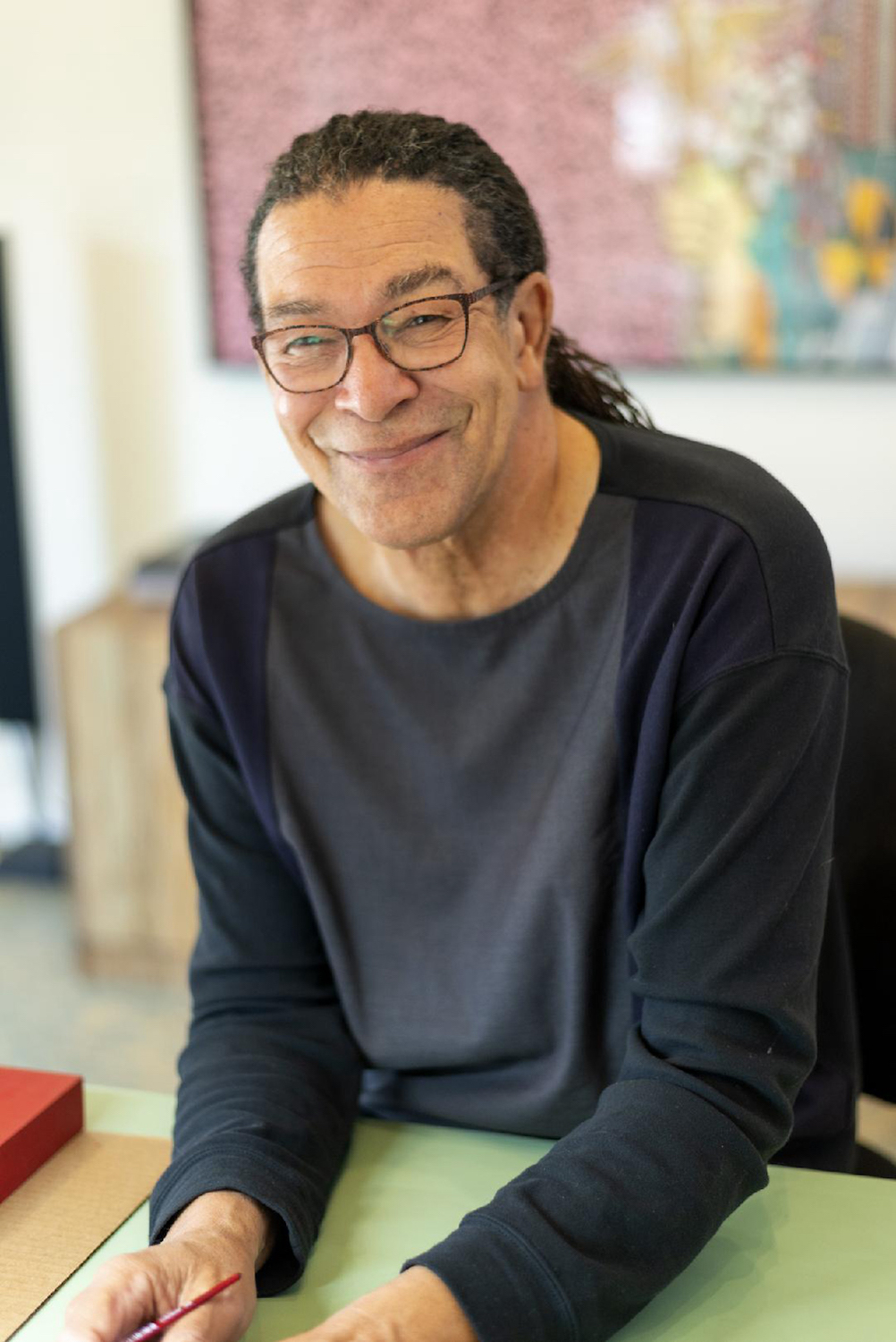

Mark Steven Greenfield Portrait, Photo Credit Tony Pinto A native Angeleno, Greenfield is receiving well-deserved recognition. Besides being a full-time artist, he has had an

extraordinary career as a significant cultural producer in the roles of arts administrator, curator, juror and teacher in Los Angeles. Like many artists who have a hybrid career in the arts, Greenfield worked as Art Center director at the Watts Towers Arts Center and director of the Los Angeles Municipal Gallery for the Cultural Affairs Department, City of Los Angeles. His associations with over 25 cultural and service organizations are a testament to his ethos of service and support for artists and community.

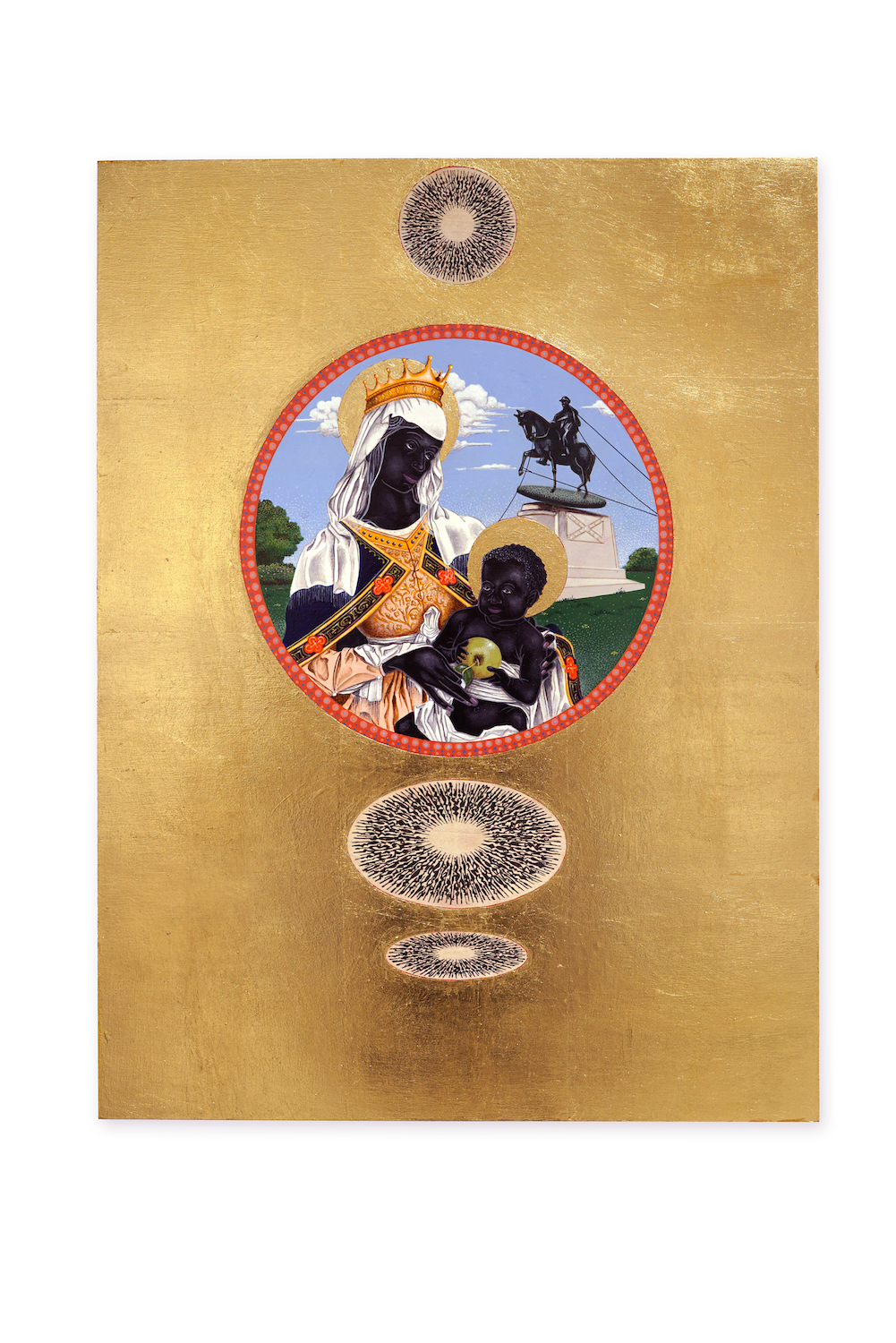

Toppling, 2020, Acrylic and Gold Leaf on Wood Panel, 24” x 18” Raised a Catholic and a long-time practitioner of meditation, Greenfield infuses his work with allusions to ritual, ceremony and spirituality. Painting images of Black and brown persons on gilded panels in a meticulous narrative, representational style, “Black Madonna” and “HALO” become symbols of empowerment and unification. When Greenfield alludes to the protective and healing purposes of traditional religious icon art, he suggests his work is also meant to offer similar forms of protection. Both his series clearly respond to the killings of African Americans by the people who are supposed to keep our communities safe. Greenfield says of his recent paintings that they “conjure up memories of the church and the reverence once paid to statues and images of saints,” but are now redirected to those who have taken up the struggle for social justice. He adds, “I made the choice of honoring those little known heroes, martyrs and personages from whose stories we might gain strength.”

Escrava Anastacia, 2020, Acrylic and Gold Leaf on Wood Panel, 24″ X 24” Greenfield’s art practice explores and illuminates the Black experience, focusing on the effects of stereotypes on American culture. Always provocative in an unexpected way, his work stimulates a much-needed and often long-overdue dialog on issues of race. His recent summer exhibition, “HALO,” has created another conversation. While “Black Madonna” played with the idea of role reversals—revering and worshiping a Black Virgin Mary and a Black Baby Jesus as symbols of love; what if white supremacists were the victims instead of the oppressors—“HALO” evolved as a next natural progression, highlighting historical Black figures. They have been chosen from the period of the slave trade during the 1400s–1800s. He wants his subjects—often legendary in their time yet now overlooked—to be rediscoverd. Greenfield’s use of gold as a material connotes value and importance, but also currency. Most of the people depicted in the series were enslaved and treated as commodities. His figurative painting is particularly striking. Greenfield explains,“The figures are rendered in ‘ultra-black’ in keeping with their political designation and not so much for their degree of melanin. It is the element in these paintings that unifies, regardless of association, wealth, class or prestige.” Almost all of the paintings have circular glyphs, a visual device that is a through line in much of Greenfield’s work. These evoke the mantras he uses as a vehicle in his daily meditations.

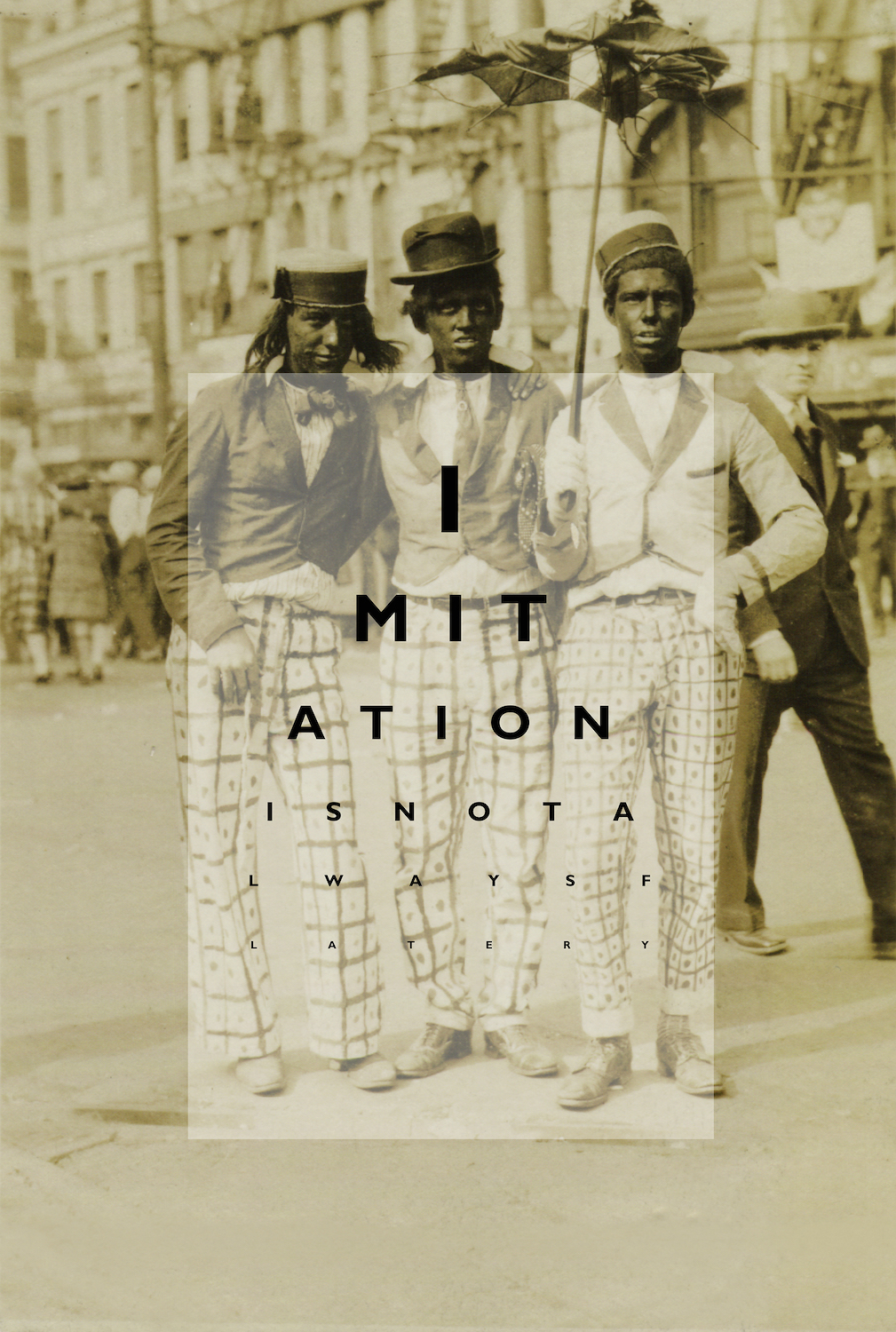

Lesson, 2002, Ink Jet Print, 37″ X 28″ In Greenfield’s work, each series has developed its own stylistic approach. For example, his 2007 exhibition “Incognegro,” at the 18th Street Arts Center, consisted of appropriated photographs. They are mainly of white people in black face, who in turn were appropriating African American culture. For this body of work, he made Iris prints and lenticular photographs. The mirror effect of lenticular photography heightened Greenfield’s intention to expose and dramatize the complexities surrounding issues of race, identity and perception. With the photos of turn-of-the-century black-face performers he superimposed a subversive message that looks like a optometrist’s office eye chart. They contain direct, challenging statements and questions about race and identity. “Incognegro” caused a stir about the use of Black stereotypes and whether they were helpful or hurtful. Mark says of this experience, “Work dealing with the indignities associated with black face has always been a messy proposition.” He believes that black-face images have haunted communities of color for a long time. His intention with this series was exorcising the demons that these images have conjured up; without that, he says, “We’ll never really be free. “Incognegro,” while problematic in 2007 for some segments of the Black community, is starting to impact whites, compelling some degree of introspection on their part. It has brought into focus the responsibilities associated with social justice and allyship. Both “Black Madonna” and “HALO” expand this conversation and engagement with a larger audience that is willing to listen and learn from the social reckoning occurring globally and locally. At a moment when many younger artists of color are gaining national attention for their identity-based work, Greenfield has always been creating conversations about racial reckoning, both as an artist and cultural producer. His unswerving commitment to self-examination and community has made him a change-maker in the best sense of the word.