Your cart is currently empty!

Tag: black art

-

Fire and Water

The Beautiful Tragedies of Calida RawlesIn 2004 Calida Rawles moved from New York to Los Angeles, and she found an art scene brimming with life. Trained as an artist, she longed to become part of that world, and asked herself whether she would become a collector or a painter. She decided to give herself the chance to be a painter and made an agreement with her husband that she would take a year to find her way, without any expectations of financial return. She rented a studio—the studio we are in now, in a repurposed industrial building in Inglewood—and she began to explore and experiment.

Among the first works to emerge were self-portraits of herself crammed into an acrylic box. She still has that box—it’s in a corner of the studio, and now holds snacks and a small refrigerator to keep the drinks cool on this hot, hot summer day. “I pressed myself against this box, took pictures of myself when I was pregnant with my last baby,” she says. “Then I painted myself getting out of the box and turning into water. Those are the first ones using water as this metaphor of my release.”

Rawles was born in Wilmington, DE, to working-class parents. “Artistic expression was big in my family,” she recalls. Her mother was happy to buy art supplies for her kids, and Calida took her first painting lessons as a child. Later, she majored in studio art when she attended Spelman College in Atlanta. She wanted to continue and applied to New York University, partly because she thought her parents would be pleased that she was going to such a prestigious school.

It ended up in discouragement. “I had been so nurtured at Spelman, and then I went there [NYU], and it was a very different, tough experience.” She’s fine with how things turned out, she says, but “before I went to grad school, I think I needed to be a little bit more mature. I needed to know who I was more and have a better understanding of my voice.” It was also a time when some instructors were critical of figurative work, and questioned her focus on the Black body.

Today Rawles has clearly found herself—and gallerists and collectors have found her. In 2020 she had her first solo exhibition, “A Dream for My Lilith,” at Various Small Fires.

Rawles says she’s often more influenced by literature than by other art, and this show explored the myth of Lilith, said to be the first wife of the Biblical Adam. The artist separated Lilith from her traditional reputation of failed womanhood and moved her representation towards the notion of strength and liberation embodied by Black women and girls. Those paintings were in the main gallery, while the smaller gallery featured studies done for Ta-nehisi Coates’ book, The Water Dancer (2019). Unfortunately, that show closed early due to the COVID shutdown, but shortly thereafter Rawles was picked up by Lehmann Maupin in New York. The latter gallery featured her exhilarating portrait of a woman floating in blue water, The Way of Time, at this year’s Frieze LA.

Water is a pervasive leitmotif in Rawles’ work. In her paintings people are often seen floating or swimming in a watery environment, and they are nearly always clothed. About the time Rawles got her studio, she also began to take swimming lessons. She found that she loved both the sensation of swimming and being able to see how water captures and refracts light, and the shifting net patterns it forms. Her figures are radiant, sometimes smiling, as the subject of The Way of Time is, or sometimes with their eyes closed in meditation or serenity.

Calida Rawles, Radiating My Sovereignty, 2019. Acrylic on canvas, 84 x 72 in., 213.4 x 182.9 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul, and London. These days Rawles works in acrylics, although she has recently done some pastels. She still takes photographs, sometimes by the hundreds, to prepare for a painting. Most of the subjects are friends and family, and she photographs them in pools. Later she goes through the photographs, selecting which elements to use, such as how legs bend and become wavy when you view them through the water. As a Black woman, she is keenly aware of the politics of the Black body, and equally conscious of how lagging this country is in the treatment of Black people and of women. The ease and the confidence with which her figures navigate water are powerful statements about being in the world—we are here, we belong here, we thrive.

Rawles likes to work large, but often makes a smaller study first to work out the details. The one on her easel now features her youngest daughter, as if she were being shot out of a cannon—head forward and one arm behind her. Rawles has mentioned Degas before, and I say this one reminds me of Degas’ young ballet dancer—the bronze the Norton Simon has a version of. “I see that, too,” she says. “I think that it will be inevitable that people make associations with that work.”

In a 2021 essay for Artnet News, Roxane Gay praised Rawles’ alternative look at Black suffering. “When I first saw Calida Rawles’ 2021 painting High Tide, Heavy Armor, I felt, as I often do when I am experiencing great art, that she was offering a different way of bearing witness. In the painting, a Black man floats in crystal blue water. The photorealism of the painting is uncanny—the smoothness and glowing brown of the man’s skin, the range of blues of the water, the reflection of the sun,” Gay wrote. “There is no one near him to question or challenge his right to be in these waters. He doesn’t have to justify or explain his leisure.” The painting is a visual elegy for Kurt Reinhold, a Black man who was the father of a child at Rawles’ daughter’s daycare. In 2020 in San Clemente, he was stopped by sheriff’s deputies on suspicion for jaywalking, and during the ensuing struggle, he was shot and killed.

Such tragedies are addressed in Rawles’ work; she doesn’t shy away from sociopolitical issues. However, the painting itself is quite beautiful, as Gay says, and is in its way a celebration of life. “I want my work to inspire others,” says Rawles. “I try to be the best version of myself as I can be—I’m not always successful at it, but I’ll try as much as I can.”

This fall Rawles will be featured at the Lehmann Maupin booth at Frieze London (Oct. 12–16), and she will have a solo at their New York location in fall 2023. The large mural version of The Way of Time, made with a team of assistants, is now on an exterior wall on a walkway at Hollywood Park in Inglewood.

-

Beautyful Migrations

The Diaspora According to Njideka Akunyili CrosbyNjideka Akunyili Crosby is having quite the year. Her figurative paintings are on the walls of esteemed museums and institutions across the country, often featuring portraits of herself, friends and family. Akunyili Crosby’s unique style consists of painted, drawn and collaged elements that she blends with a distinctive photo-transfer technique. She uses imagery sourced from magazines, catalogs and her own photographs.

Born in Enugu, Nigeria in 1983, Akunyili Crosby grew up between Enugu and Lagos, and moved to the US when she was 16. Now living in Los Angeles, she brings together these varied influences, seeking spaces where they diverge and intersect. Since earning her MFA from Yale in 2011, she has had exhibitions in major institutions nationally and abroad. She received the highly coveted MacArthur “Genius” Fellowship in 2017, and the United States Artists’ fellowship in 2021. Historic, cultural and diasporic references are at the core of her work. She touches on issues that speak to many different people, places and times, all elegantly woven together in layers of visually stunning imagery.

Akunyili Crosby tells personal and collective cross-cultural stories in paintings that are captivating and contemplative. In November 2021, the Metropolitan Museum of Art commissioned the artist to create a wallpaper that has become an exemplary case of how she addresses complex issues. Made for Before Yesterday We Could Fly: An Afrofuturist Period Room, she conceived of Thriving and Potential, Displaced (Again and Again and…) (2021) a gorgeous green vinyl backdrop. The Afrofuturist installation is one of the Met’s “period rooms,”—recreations of domestic spaces intended to be studied as representations of a specific time.

The Afrofuturist Room addresses the history of the land upon which the museum was built. Called Seneca Village, the area was home to a flourishing community of landowners and tenants who were mostly Black. The city seized the land in 1857 to create Central Park and displaced the residents. The new installation recognizes this history and imagines what a period room might look like if Seneca Village had remained. In doing so, the room shifts from the tradition of focusing on one specific time and celebrates the African and diasporic belief that the past, present and future are connected.

Embracing the layered history told through the installation, Akunyili Crosby’s wallpaper includes images of an archival map of Seneca Village from 1856, which are blended with 19th century photographs of Black New Yorkers, as well as contemporary African diasporic representations. Weaving through these images are verdant okra plants, a crop with significant history as it was carried along with enslaved people through the Middle Passage from Africa to America.

As is common with Akunyili Crosby’s large-scale installations, the wall-paper was originally created as a painting on paper. Previously unseen publicly, the painting is now included in the artist’s current solo exhibition at the Blanton Museum of Art in Austin, Texas. Just four works make up the show, all of which were made during the pandemic, giving a glimpse into the artist’s life at home in Los Angeles.

Dwellers: Native One, 2019 © Njideka Akunyili Crosby, courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro, and David Zwirner, Photographer: Jeff Mclane These new works underscore Akunyili Crosby’s interest in plants, including the aforementioned okra. Having studied biology in college and grown up with parents heavily involved in science and academics, she often features the natural environment in her work. In addition to the painting now adorning the Met’s wallpaper, the other three works in the Blanton show focus closely on plant species found both in Los Angeles and Lagos. The largest work is Still You Bloom in This Land of No Gardens (2020), a self-portrait holding her young child on a porch surrounded by plants. The artist looks straight at the viewer with calm, assured and loving eyes. Her child wears a shirt adorned with the words “black is beautiful.” The pair are a ideal representation of the relationship between mother and child.

Returning to her alma mater, Akunyili Crosby’s work will also be the subject of a solo show opening in September at Yale University’s Center for British Art. The exhibition is the third and final in a series curated by Pulitzer Prize–winning author Hilton Als. The show focuses on her ongoing series The Beautyful Ones, a reference to the debut novel of Ghanaian author Ayi Kwei Armah from 1968. Titled The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born, the novel follows a man as he navigates postcolonial Ghana in a formative period of unrest, loss and political awakening. The series, begun in 2012, features portraits of Nigerian children from her family photographs, as well as images she took on trips to Nigeria.

In addition to her work as an artist, Akunyili Crosby is a dedicated climate activist. She is a founding member of the Environmental Council at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, the first of its kind for a major art museum in the US. The council provides funds for the institution’s commitment to carbon negativity and carbon-free energy and supports exhibitions and educational programs that address climate, conservation and environmental justice.

In another large-scale installation, Akunyili Crosby showed her support of climate activism by contributing to the visual campaign A Cool Million. Founded by three artist-led collectives: For Freedoms, Art + Climate Action and Art into Acres. The campaign launched in April and turned pieces by leading artists into large-scale public works that were displayed on billboards and in museum spaces across California. The goal of the initiative was to raise climate awareness and funds for the conservation of one million acres of forest that is crucial to supporting the state’s hydrological system. Her work, Dwellers: Native One (2019), was transformed into a window vinyl for the Museum of the African Diaspora (MoAD) in San Francisco. The installation, on view through mid-September, features lush, dense plants indigenous to Nigeria layered with photographic transfers of the artist and her sister in their ancestral village, as well as an image of a woman advertising African wax-cloth fabric.

In January of 2023, Akunyili Crosby is set to kick off the exhibition program for David Zwirner’s new Los Angeles outpost. As LA begins to feature more of her work, she celebrates the similarities and differences between her African heritage and new home.

Visually stunning, captivating and laden with significance, she always tells complex, transnational stories and underscores the beauty of embracing multiple cultures.

See more of Akunyili Crosby’s work upcoming at Yales Center for British Art, then showing at The Huntington Feb 15-June 12, 2023.

Info: https://britishart.yale.edu/news-and-press/announcing-hilton-als-series-njideka-akunyili-crosby -

Racial Reckoning

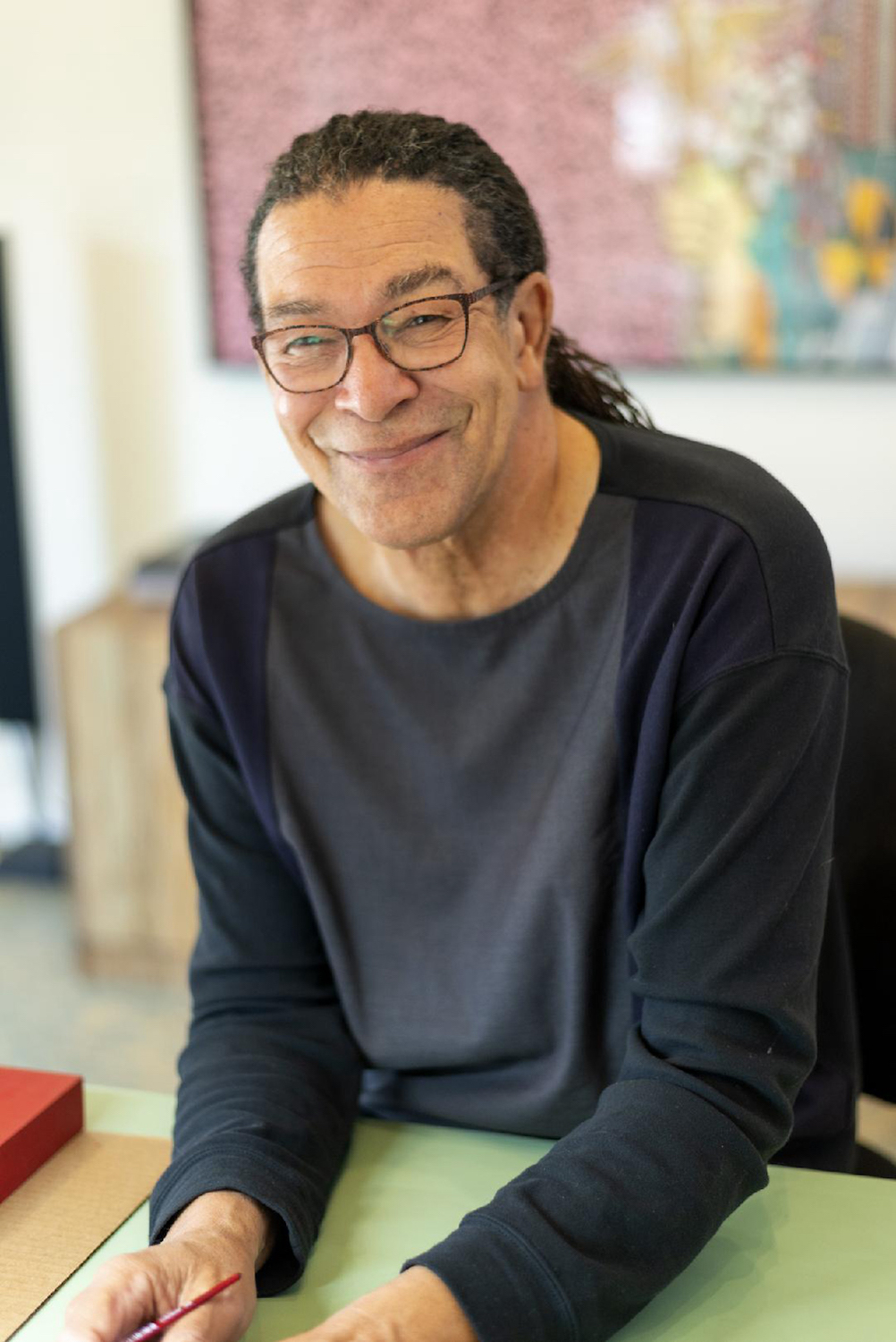

Mark Steven Greenfield Illuminates the Black ExperienceIn 2020, Mark Steven Greenfield unveiled a new body of work, “Black Madonna,” followed by “HALO” in 2022, both at the William Turner Gallery in Santa Monica. Gallery owner William Turner told me in an email that the “Black Madonna” show was a natural progression of Greenfield’s career of investigations into race and racial identity. “It was a sensation when we opened it in the fall of 2020,” Turner says. “It was purely coincidental, but after the summer of George Floyd and Black Lives Matter, our show became a catalyst for people discussing these issues.” Turner witnessed viewers staying nearly an hour in the gallery studying Greenfield’s intricate paintings. “We have never had a show that had that kind of depth of impact.”

Mark Steven Greenfield Portrait, Photo Credit Tony Pinto A native Angeleno, Greenfield is receiving well-deserved recognition. Besides being a full-time artist, he has had an

extraordinary career as a significant cultural producer in the roles of arts administrator, curator, juror and teacher in Los Angeles. Like many artists who have a hybrid career in the arts, Greenfield worked as Art Center director at the Watts Towers Arts Center and director of the Los Angeles Municipal Gallery for the Cultural Affairs Department, City of Los Angeles. His associations with over 25 cultural and service organizations are a testament to his ethos of service and support for artists and community.

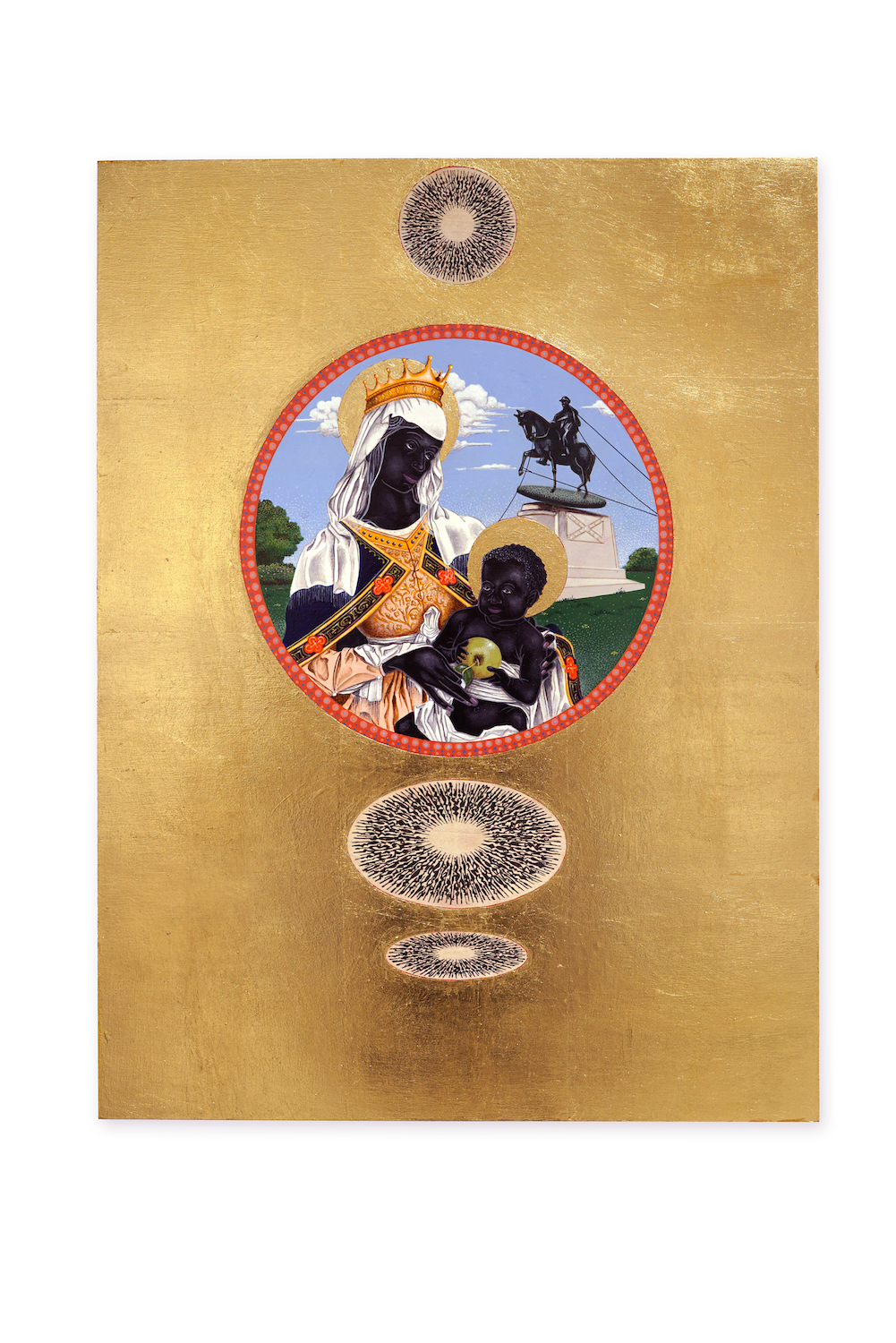

Toppling, 2020, Acrylic and Gold Leaf on Wood Panel, 24” x 18” Raised a Catholic and a long-time practitioner of meditation, Greenfield infuses his work with allusions to ritual, ceremony and spirituality. Painting images of Black and brown persons on gilded panels in a meticulous narrative, representational style, “Black Madonna” and “HALO” become symbols of empowerment and unification. When Greenfield alludes to the protective and healing purposes of traditional religious icon art, he suggests his work is also meant to offer similar forms of protection. Both his series clearly respond to the killings of African Americans by the people who are supposed to keep our communities safe. Greenfield says of his recent paintings that they “conjure up memories of the church and the reverence once paid to statues and images of saints,” but are now redirected to those who have taken up the struggle for social justice. He adds, “I made the choice of honoring those little known heroes, martyrs and personages from whose stories we might gain strength.”

Escrava Anastacia, 2020, Acrylic and Gold Leaf on Wood Panel, 24″ X 24” Greenfield’s art practice explores and illuminates the Black experience, focusing on the effects of stereotypes on American culture. Always provocative in an unexpected way, his work stimulates a much-needed and often long-overdue dialog on issues of race. His recent summer exhibition, “HALO,” has created another conversation. While “Black Madonna” played with the idea of role reversals—revering and worshiping a Black Virgin Mary and a Black Baby Jesus as symbols of love; what if white supremacists were the victims instead of the oppressors—“HALO” evolved as a next natural progression, highlighting historical Black figures. They have been chosen from the period of the slave trade during the 1400s–1800s. He wants his subjects—often legendary in their time yet now overlooked—to be rediscoverd. Greenfield’s use of gold as a material connotes value and importance, but also currency. Most of the people depicted in the series were enslaved and treated as commodities. His figurative painting is particularly striking. Greenfield explains,“The figures are rendered in ‘ultra-black’ in keeping with their political designation and not so much for their degree of melanin. It is the element in these paintings that unifies, regardless of association, wealth, class or prestige.” Almost all of the paintings have circular glyphs, a visual device that is a through line in much of Greenfield’s work. These evoke the mantras he uses as a vehicle in his daily meditations.

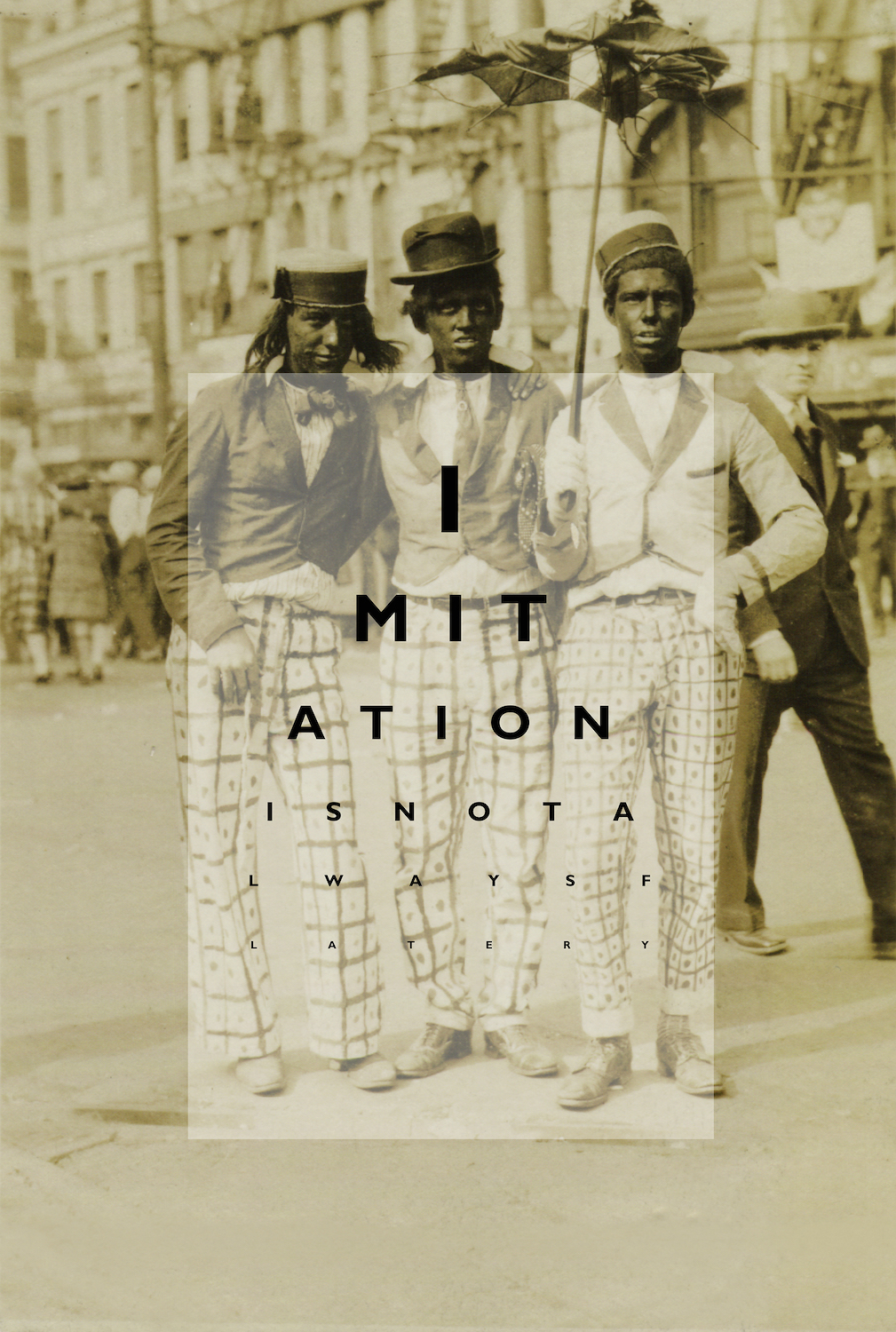

Lesson, 2002, Ink Jet Print, 37″ X 28″ In Greenfield’s work, each series has developed its own stylistic approach. For example, his 2007 exhibition “Incognegro,” at the 18th Street Arts Center, consisted of appropriated photographs. They are mainly of white people in black face, who in turn were appropriating African American culture. For this body of work, he made Iris prints and lenticular photographs. The mirror effect of lenticular photography heightened Greenfield’s intention to expose and dramatize the complexities surrounding issues of race, identity and perception. With the photos of turn-of-the-century black-face performers he superimposed a subversive message that looks like a optometrist’s office eye chart. They contain direct, challenging statements and questions about race and identity. “Incognegro” caused a stir about the use of Black stereotypes and whether they were helpful or hurtful. Mark says of this experience, “Work dealing with the indignities associated with black face has always been a messy proposition.” He believes that black-face images have haunted communities of color for a long time. His intention with this series was exorcising the demons that these images have conjured up; without that, he says, “We’ll never really be free. “Incognegro,” while problematic in 2007 for some segments of the Black community, is starting to impact whites, compelling some degree of introspection on their part. It has brought into focus the responsibilities associated with social justice and allyship. Both “Black Madonna” and “HALO” expand this conversation and engagement with a larger audience that is willing to listen and learn from the social reckoning occurring globally and locally. At a moment when many younger artists of color are gaining national attention for their identity-based work, Greenfield has always been creating conversations about racial reckoning, both as an artist and cultural producer. His unswerving commitment to self-examination and community has made him a change-maker in the best sense of the word.

-

GALLERY ROUNDS: Black Kirby

UCR Arts, Culver Center for the ArtsThe creation of Black superheroes in Marvel Comics during the Silver Age (comics published from 1956–1970) and Bronze Age (comics published from 1970–1984) has consistently been the exception and not the rule. There was Black Panther (1966), Blade (1973) and Monica Rambeau as Captain Marvel II (1982), just to name a few. However, in a parallel universe, pre-Afrofuturism birthed Ebon (1970) by Larry Fuller. The company Milestone Media Inc. — founded by Derek Dingle, Dwayne McDuffie and Denys Cowan — produced Icon (1993), Hardware (1993), and Static (1993). Lastly, L.A. Phoenix (1994) originated from the mind of David G. Brown.

Portrait of Jennings & Robinson Enriching today’s critical race theory discourse, Stacey Robinson (Assistant Professor of Graphic Design and Illustration, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign) and John Jennings (Professor of Media and Cultural Studies at UC Riverside) teamed up to form the collaborative project Black Kirby, bringing to UCR two transformative exhibitions — “Ebon: Fear of a Black Planet” and “Black Kirby X: Ten years of Remix and Revolution.” This team’s provocative name expressed with an illustrative aesthetic style originates from classic comic book artist, Jack Kirby, and their art unapologetically interrogates while addressing themes connected to Afrofuturism, social justice and representation with Hip Hop as a framework.

In “Ebon: Fear of a Black Planet,” Black Kirby’s collaborative efforts with Larry Fuller, a pioneering Black cartoonist who worked in San Francisco’s underground comics movement, reimagined the Black superhero, Ebon. His abilities were similar to that of the DC comic’s Superman; however, his strength came from darkness. Envisioning Blackness both as a safe and brave space are the various renditions of Ebon. Of significance is the image of him flying with a blue-black cape snaking into the S shape complementing both arms outstretched. Moreover, the explosively red halo surrounding the frontal profile communicates that Ebon has arrived and he ain’t playin’ either!

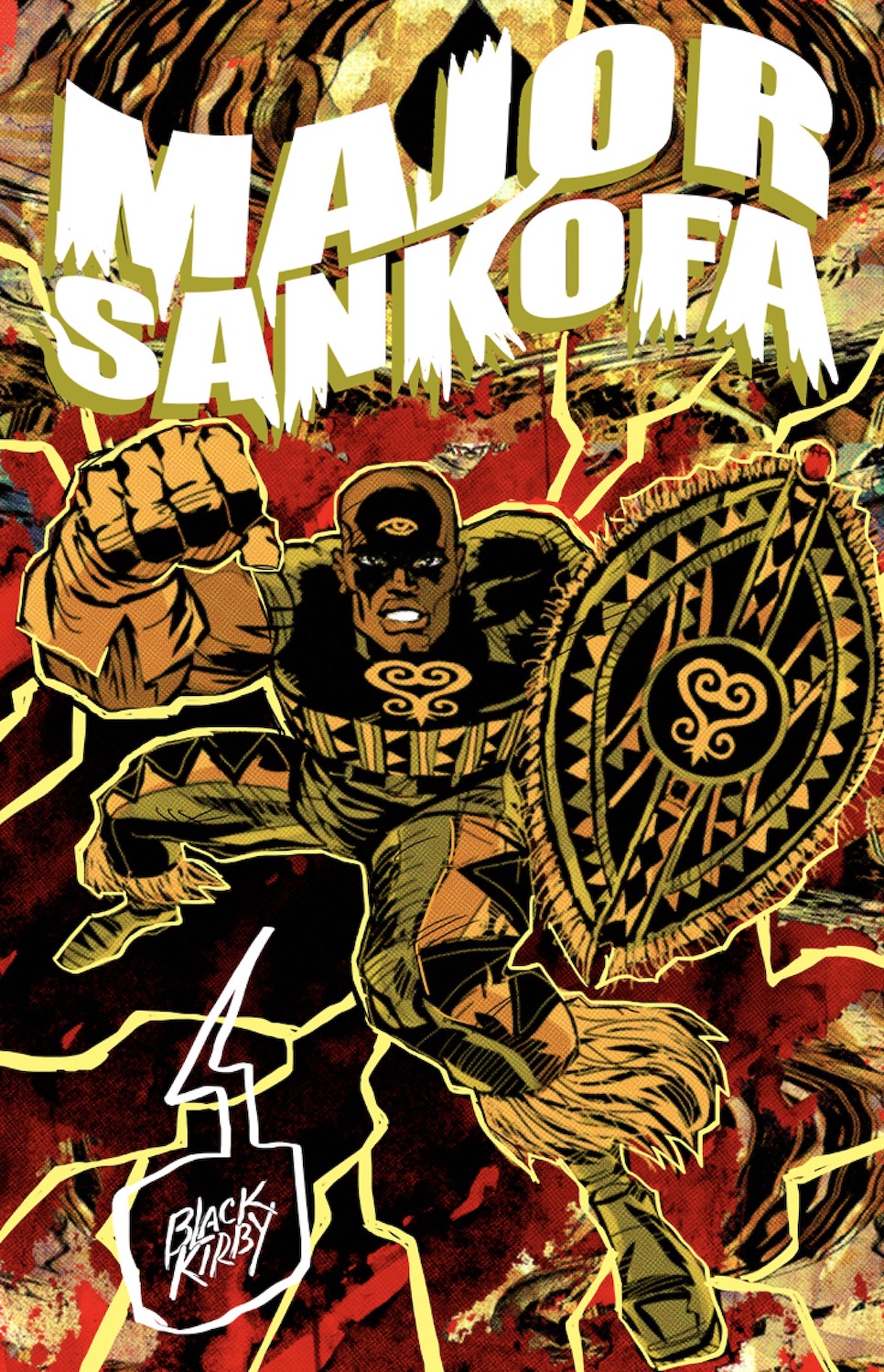

Major Sankofa With eye-pop-locking gold, orange and red hues, the digital rendering of Major Sankofa mirrors the Captain America #193 cover drawn by Jack Kirby in 1976. However, in this remixed version, the major with a confident frontal profile wears a Kente zig-zagged costume with an Africanized shield in one hand and the other enclosed as a fist. In fact, one can almost hear James Brown singing “Superbad.”

Motherbox Celebrating sistahs Blacknificently is Motherbox, a digital rendition of a Black woman in profile pose adorned in royal apparel holding a glowing object within an interstellar space background.

Viewing Ebon: Fear of a Black Planet and Black Kirby X: Ten years of Remix and Revolution is an inspirational requirement for anyone wanting to be a hero in their own circle of influence, positively changing this world one person at a time.

Ebon: Fear of a Black & Black Kirby X: Ten years of Remix and Revolution

UCR Arts: Culver Center for the Arts

March 19, 2022 to June 19, 2022

3824 +3834 Main Street

Riverside, CA 92501 -

GALLERY ROUNDS: Museum of Art and History Lancaster

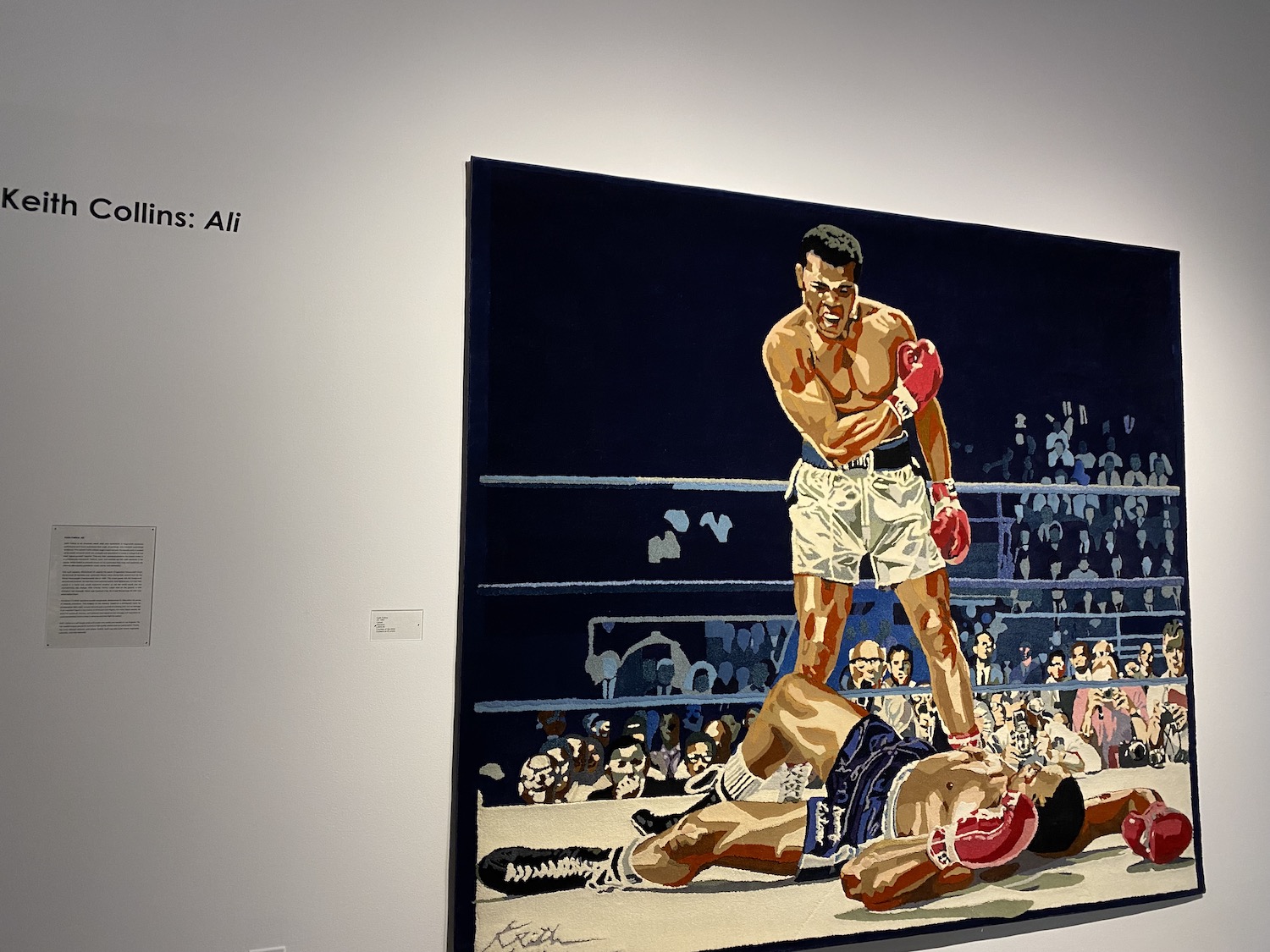

Group Exhibition “Activation”Comprising seven different exhibitions, “Activation” is an exciting series of works from six individual artists as well as a selection of activist graphics. Featured artists and their exhibitions include Mark Steven Greenfield, April Bey, Carla Jay Harris, Keith Collins, Paul Stephen Benjamin, Sergio Hernandez and the Collection of Activist Graphics from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Taken individually and as a whole, the exhibitions offer an invigorating mix of mediums and styles. Bey’s lush The Opulent Blerd uses tactile mediums and vivid color to express power dynamics, including that of the advertising and fashion industries regarding people of color. Smart, witty and trenchant, Bey’s exquisitely constructed work is also simply beautiful.

April Bey, The Opulent Blerd Equally lovely are the gilded, fantastical images of Harris’ A Season in the Wilderness. Infused with light and a sense of magic, Harris shapes boldly hued visuals myths both mysterious and captivating. With gold leaf elements that mirror that of Byzantine icons, Greenfield’s “A Survey, 2001-2021″ creates powerful paintings that subvert negative stereotypes about Black people and culture. Like Bey and Harris, a fierceness in palette matches passion for his subjects, serving as a framework for a message of pride, hope, achievement and sacrifice.

Mark Steven Greenfield, “A Survey, 2001-2021″ , photo by Genie Davis. Collins’ incredible use of repurposed material to create tapestry is on full display with Ali, a woven miracle of second-hand fiber creating a visceral tribute to the great fighter —and first-class art. Audio and video elements are also approached as woven material, with Benjamin’s stirring Oh Say (Remix), combining iconic American imagery with voices of black artists performing The Star-Spangled Banner.

Keith Collins Ali on view at MOAH. Photo by Genie Davis. Hernandez’ collection of work is also potent, presenting satiric graphic and comic art in Chicano Time Capsule, Nelli Quitoani; a variety of graphic fine artists’ work is displayed in “What Would You Say.” These two exhibitions, while less visually galvanizing than the others on displa, nonetheless richly round out a show soaring with imagination and beauty while educating viewers and redefining its subject matter with a sense of purpose and change.

MOAH is located at 665 W Lancaster Blvd, Lancaster, open Tuesday-Sunday.

-

GALLERY ROUNDS: Sonya Fe

Riverside Art MuseumSky-rocketing gasoline prices accompanied by worries of war in Ukraine even as the planet attempts to turn the pandemic corner is more than enough to hold happiness hostage. However, Sonya Fe’s exhibition “Are You with Me?” at the Riverside Art Museum recaptures the playfulness of childhood youth where every day seems like holiday stay-cation, binge-watching Saturday morning cartoons and humming Sesame Street’s theme song while snacking on a jelly sandwich. In this 21st century, anxiety has become the kryptonite for a memorable childhood; however, Fe’s work courageously honors and affirms youthful human experience emersed in hope.

Her skillful interpretation of the figure in these oil paintings mirrors the Mexican masters: Khalo, Rivera, Orozco and Siqueiros, in a first reading of these works. However, the significant difference is Fe’s conscious choice to focus on children as primary subject matter, aesthetic intentionality celebrating the soul of these little ones.

Even While Sitting, Kids are Kinetic with Energy ( 2018) depicts a girl adorned in an ivory dress with a puzzled yet impatient expression indicating frustration in being still while sitting in a sky-blue and cherry-red chair. The puppies held in each hand with a leash are standing, ready to scurry away. The contrasting hurricane swirl of plants—ranging from popsicle orange to Christmas-tree green—with the momentarily peaceful child suggests that rambunctiousness has a beginning. In fact, similar to Cristina Cárdenas’ Yo Soy/Myself (1996), this depiction of the sitting child reflects Fe’s proficiency at communicating much with simplicity.

Installation view, Sonya Fe “Are You with Me?” at the Riverside Art Museum, 2022. In Grandpa’s Truth ( 2020), Fe’s versality shines through with a hint of cubism similar to Charles Alston’s Family (1955) in her portrayal of two caramel complexioned children. The young boy is wearing a snowy shirt held in place with coffee-colored suspenders as he proudly holds a book at his side titled Black History. Next to him appears to be his sister in a pearly neutral dress staring as if wanting to greet viewers. The red chair dances compositionally against the pineapple-yellow strokes shaping the room’s wall.

Ultimately, this show contributes to the dialogue surrounding contemporary Chicana and Chicano art. Sonya Fe’s exhibition is a must-see.

Sonya Fe: Are You With Me ?

October 16 2021-May 29, 2022

3425 Mission Inn Avenue

Riverside, CA 92501

-

Black Grief Examined at New Museum, NY

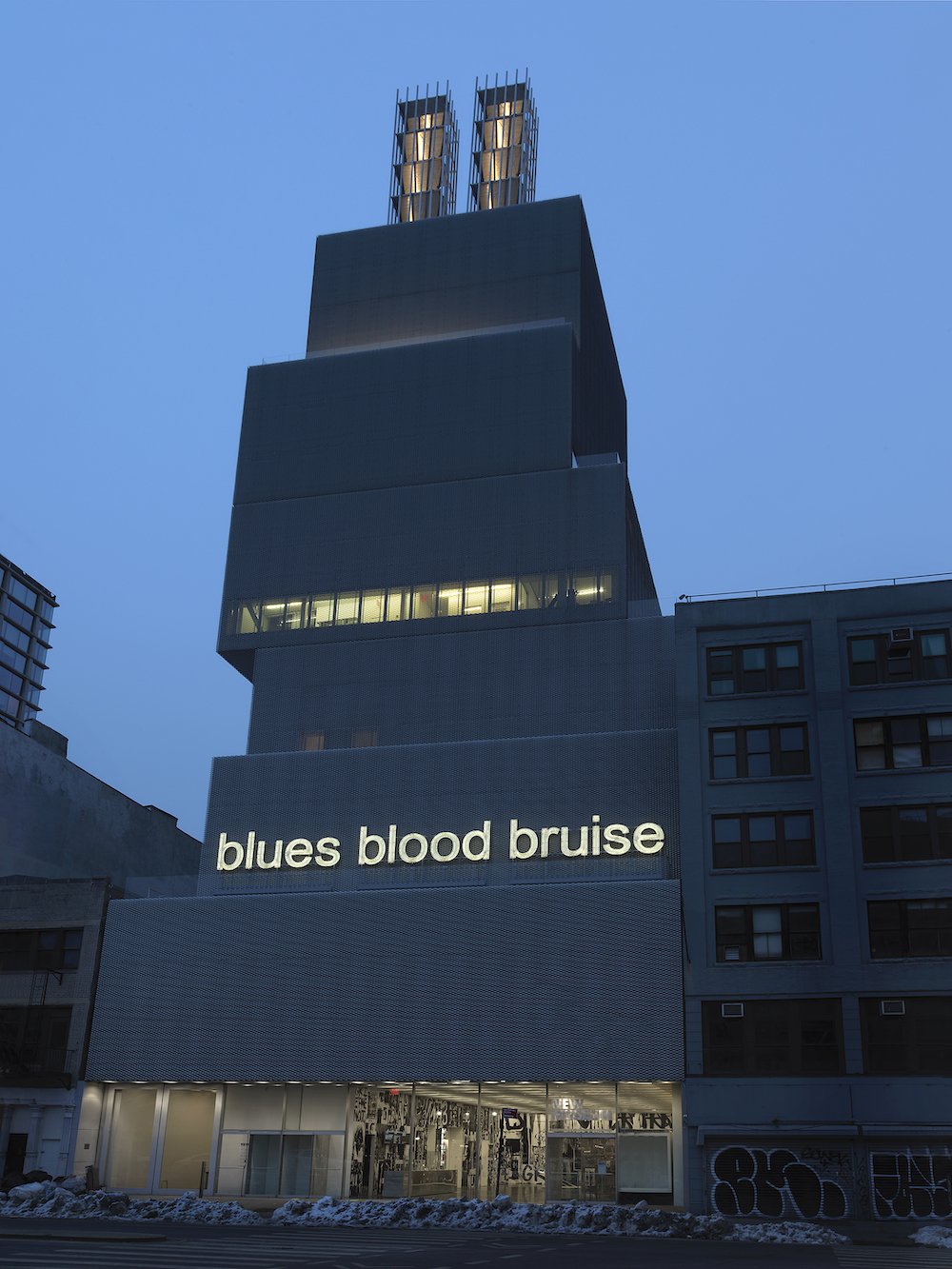

“Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America” By Okwui EnwezorGrief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America, 2020

By Okwui Enwezor

264 pages

Phaidon/New Museum, New York

In a pivotal scene in Francis Ford Coppola’s film The Godfather a Mafia don grieves over the body of his dead son. “Look how they massacred my boy,” the weeping father intones, and the audience grieves with him. A worldwide audience is moved by the pantomime death of a handsome movie actor.

Another dead son, this one truly dead and made so just a few years after the theatrical death, is viewed in an open coffin. He is just a boy, and he is disfigured, gruesomely distorted. He is missing an eye, he is swollen, and he is, was, real. Upon the perpetrators there is no comeuppance visited. There is no justice.

“Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America,” 2021. Exhibition view: New Museum, New York. Photo: Dario Lasagni In Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America—a piercing title that recalls the Reagan era—the late author and curator Okwui Enwezor had envisioned an exhibition where writers and artists excavate, examine and enliven the antithetic of Black and America. His death at age 55 prevented his completion of the project but it has been dutifully and beautifully realized by Naomi Beckwith, Massimiliano Gioni, Glenn Ligon and Mark Nash.

Tiona Nekkia McClodden, THE FULL SEVERITY OF COMPASSION, 2019 in “Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America,” 2021. Exhibition view: New Museum, New York. Photo: Dario Lasagni. The book by Phaidon and exhibition at the New Museum feature the work of essayists and artists whose work is both moving and haunting. Considering the historical similarities between Black deaths in the antique and the contemporary, Saidiya Hartman, in her essay, Dead Book Remains, conflates the horrors visited on past and present Black bodies as being something to be expected; that while their labor may have value their personhood does not. In My Soul Looks Back in Wonder Naomi Beckwith records the evolving status of images of negritude, from persecution to resistance, and specifies how the co-option of Black pain as seen in the Whitney Biennial’s choice of artist Dana Shutz’ Open Casket (2016) painting of the decomposed Emmett Till was so cack-handedly considered; a throwback souvenir for unreconstructed white folks, like baseball manager John McGraw’s lynching rope souvenir, or dreadlocked ski-bums in Vail.

The artworks featured include The Full Severity of Compassion (2019) by Tiona Nekkia McClodden, a fully blackened cattle squeeze chute, suggestive of bodily coercion, experimentation and consumption. Similarly haunting is Drainer (2018) by Julia Phillips, a ceramic cast of a woman’s torso suspended above a concrete shower drain, a peculiar bodily dissection of unknown or willfully dismissed history.

Julia Phillips, Drainer, 2018 in “Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America,” 2021. Exhibition view: New Museum, New York. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Many of the artists included are so widely known that their contributions become less powerful. Celebrity transforms their work into spectacle, clouding the visceral bite they might otherwise convey. The majority of works and essays, however, reach deeply into our sensibilities, insisting that we either embrace or dismiss, to vehemently choose sides.

Yet the rise of righteous protest and demand versus the naked and eager retaliation that it faces has not prefigured a concluding détente but a death spiral of the republic, suggesting that any hope of equity will ultimately devolve into a tense and simmering stalemate.