Your cart is currently empty!

Tag: art films

-

FILM: SECOND ACTS

While sagas of personal transformation are a staple of recent nonfiction filmmaking—from U.N. peacekeeper Roméo Dallaire’s inexorable drift into despair (and back) in the CBC’s Rwanda documentary Shake Hands With the Devil, to crack-mom Kirk White’s unexpected ascent into rehab in the Dickhouse sleaze-fest The Wild and Wonderful Whites of West Virginia—two entries in the 2013 Los Angeles Film Festival take the motif a significant step further. In Tamar Halpern and Chris Quilty’s Llyn Foulkes One Man Band, a contender in the Documentary Competition, and in Josh Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing, exhibited as part of festival’s International Showcase, the filmmakers themselves, standing outside the frame but very much part of the picture, take on the role of confessor, facilitating—or in Oppenheimer’s case, guiding—their subjects’ journey toward a deeper appreciation of their human condition and pointing the way forward to one or another species of redemption.

In opening his heart to Halpern and Quilty, for example, artist-musician Llyn Foulkes pushes through to levels of self-understanding that may no longer be available to him qua artist-musician. Over the more than seven years (2004–2012) it took to shoot the film, its subject—who is never less than honest with his interlocutors, and who over time comes to suspect that “artists don’t have effects any more” (see also Auden’s “Poetry makes nothing happen”)—provides ample glimpses into his personal history and studio practices even as his mood shifts from a reflexive sense of injury at the hands of the LA art establishment (“Is it ever going to be my time?”) to a pained acknowledgment of his penchant for self-sabotage (“I’m not very friendly” or “I’m too self-centered”) and a wholesale reassessment of his vocation (“I’ve put art on too high a pedestal” and “I’m tired of being a one-man band”). Meanwhile, the filmmakers’ narrative line takes us from a chronicle of perceived insult and injury, reaching its nadir in the aftermath of 2004’s poorly attended group show at New York’s Kent Gallery (to which Foulkes contributed a single large painting), to one of triumphant vindication, culminating in a 2011 Art in America cover story and in this year’s widely attended, universally lauded career retrospective at the Hammer. (If the show had a metacritic.com rating, it would be somewhere in the high 80s.)

film still from Llyn Foulkes One Man Band As the story line changes, so do the questions raised in the talking-head commentary by curators, critics and other artists, from “Why hasn’t Foulkes achieved the kind of recognition and earning power accorded other Ferus alumni?” to “Is Foulkes finally about to achieve the kind of recognition and earning power accorded other Ferus alumini?” to “Will success spoil—no, make that satisfy—Llyn Foulkes?” “Perhaps!” answer the filmmakers, though not as confidently as that exclamation mark might suggest.

While Llyn Foulkes’ repeated threats to “quit art” if “something doesn’t happen this time” (the art-world equivalent of Eric Cartman’s “Screw you guys, I’m going home!”) may, post-Hammer, seem a case of flogging an already decomposed horse—the slack final third of Halpern and Quilty’s film shares a little of this quality—the end result of all that Sturm und Drang in all the aforementioned movies lies, of course, outside their time frame. Maybe even outside time.

How ephemeral, after all, is the issue of our best intentions? In the case of Anwar Congo, chief among the decidedly inhuman human protagonists of the Danish-British-Norwegian coproduction The Act of Killing, we must suspect the worst. In a surreal variation on the truth-commission process that attained prominence following the fall of South Africa’s apartheid government and during Rwanda’s post-civil-war reconstruction, London-based filmmaker Josh Oppenheimer offered a group of elderly, well-heeled Indonesian thugs who, in the 1960s, were enlisted by the Suharto government to carry out genocide against more than a million Indonesian “communists” the opportunity to stage reenactments of their crimes against humanity—on camera, with a budget, and props, and costumes, and with a mandate to recreate their favorite American film genres! Predictably, gangster films, horror films, and westerns figure prominently, as do Bollywood-style production numbers. And where did Congo and company turn for their extras? To the very neighborhoods and villages they had terrorized 50 years earlier, casting as victims both the children of those they had terrorized, many of them witnesses to the original atrocities, and the hitherto insufficiently traumatized grandchildren of the historical victims, kids who no doubt grew up listening to eyewitness accounts of those same atrocities.

All of which makes for an unbelievably interesting and original documentary—so interesting and original, in fact, that when Werner Herzog and Errol Morris saw early cuts of The Act of Killing, they immediately signed on as executive producers. Which is no surprise, given the levels of weirdness involved. Over and above the already enumerated grotesqueries of Oppenheimer’s film—grotesqueries which shouldn’t, by the way, be mistaken for the point of the exercise—is the fact that the dapper Congo and his less fashion-forward colleagues (one of them with a penchant for cross-dressing) are by no means pariahs in present-day Indonesia.

Quite the contrary. In the minds of many Indonesians—not least of all the members of the paramilitary Pancasila Youth organization to which Congo and his cronies today act as advisors and role models—anti-communism is still, as it was under Suharto, the state religion. For these young fascists, in their inappropriately garish red-and-black camouflage outfits, the old-school perpetrators of so many shootings, garottings and beheadings, to say nothing of their enthusiastically enhanced interrogation techniques—all arguably conducted more for the sake of purging Indonesia of ethnic Chinese than of actual communists—are culture heroes.

And so it goes, until one of those culture heroes—in the interest of adding another dash of spice to his legacy—puckishly announces his intention to play the victim in one of the grislier reenactments. (“Come watch grandpa get tortured and killed!”) That, folks, is the turn of events that puts The Act of Killing firmly in step with the through-line of the report you’ve just finished reading.

THE ACT OF KILLING

A film by Joshua Oppenheimer

On DVD this November.LLYN FOULKES ONE MAN BAND

A film by Tamar Halpern & Chris Quilty

To be released in 2014; check FB page

llynfoulkesonemanband for schedule of college & museum preview screenings. -

FILM: In the Shadows, Cutie and the Boxer

Most stories about larger-than-life male artists and their girlfriends/wives share a familiar arc—he overshadows her. When Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner bought a house in East Hampton, Pollock got to work in the barn, Krasner painted in the bedroom. It was only after his death from a car crash that she moved into the barn and began making her most extraordinary body of work.

There are echoes of the Pollock/Krasner relationship in Cutie and the Boxer, a documentary about the unlikely marriage of Ushio Shinohara, notorious bad boy of 1960s Japanese avant-garde art, and Noriko, a quiet art student when they met in New York. This much older, charismatic man swept Noriko off her feet, but also threw her into his macho shadow. Forty years later the clashes and resentments are out in the open, as Noriko struggles to emerge as a person and as an artist in her own right.

Director Zachary Heinzerling met the Shinoharas as Noriko began carving her own studio space out of their cluttered Brooklyn flat. He also found some remarkable vintage footage, and skillfully intercut it with new segments. In the 1960s Ushio Shinohara became famous for his action paintings, especially ones in which he donned boxing gloves and punched splatters of color onto paper and canvas. (Yes, Pollock was an inspiration for him.) Then he left Japan for the wider art world of New York, but never really made it big.

Beneath her lovely serene face, Noriko is seething. Forty years ago, at 19, she came to New York to study art, then fell in love. She let go of her education, her own career, to become wife and assistant. They had one son, who makes occasional appearances in this film, including one where he is surreptitiously boozing in the kitchen—an alcoholic like his father. There are scenes so raw they make you squirm—Ushio gets rip-roaring drunk and stumbles and shouts during dinner with friends, Noriko bitterly berates him for his selfish behavior. If you thought Japanese people were only repressed and decorous in their interactions with one another, think again.

Sometimes Ushio does try to shoulder some responsibility—one poignant section shows his preparing to leave for Japan, on a selling trip. He’s a vigorous 80, but it can’t be easy having to travel halfway around the world to sell his own wares. He crams artwork into his luggage as Noriko watches.

During the course of the film, an art dealer comes to look at Ushio’s work, and Noriko makes sure he takes a look at hers, too. A joint exhibition is planned, and both make new work for it. Noriko’s work is on the illustrative side and features her alter ego, Cutie, who often has to put up with the shenanigans of her partner, Bullie. The surrealistic scenes are self-revealing, and that both frightens and exhilarates her.

At the end of the film they’re sitting together, admitting that they’re still in love. While you know Noriko has made tremendous sacrifices to keep the marriage going, you also wonder about the strength and resilience that struggle has given her—and when we’re going to see her work exhibited solo.

CUTIE AND THE BOXER

A film by Zachary Heinzerling -

Seeing The Big Picture

Stanley Kubrick’s filmmaking career begins and ends in a mood of urban claustrophobia—at its earliest stages, gritty and almost inarticulate, yet full of expression; at the end, almost hyper-articulate yet inchoate; refined, even rarefied, yet darkly, mortally carnal, unfolding its waking-unconscious narrative in a space that is as simultaneously closed and expansive as its protagonist’s mind. Over the course of 50 years of developing and directing films, Kubrick was to open and physically amplify those spaces, casting ever wider lenses in every direction to the sky and beyond.

Many of those same lenses are displayed in a vitrine in Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s “Stanley Kubrick” exhibition, which originated at Frankfurt’s Deutsches Filmmuseum. Although they may be of more interest to film professionals, they are not incidental here. At the risk of legitimizing a battered and near-meaningless phrase of some currency in media circles, no one understood the “optics” of a situation—in every sense—better than Kubrick did. Beyond understanding how perceptions were shaped was his understanding of how every aspect of their representation shaped story and outcome. Whether in a chiaroscuro, half-tone world of black and white and hazy grays, or sanguineous and richly saturated color, Kubrick’s films show us matters of sense and sensibility trumping abstract notions of order, perspective, control, belief; the whole contained and magnified by the story moving across the screen. What remains consistent through these very distinct films, is a preoccupation with the juxtapositions and intersections of interior and exterior spaces, and parallel to that, physical and psychological spaces. In Kubrick’s movies, we are always acutely aware of how where and what the characters see condition the way they see, and vice-versa.

Kubrick’s gift for grafting a dramaturgy of space and perspective to the dramaturgy of script and performance was unique. There is a stunning economy, almost bluntness, of character development evident from the earliest of Kubrick’s films to the very end. Kubrick understood the craft of photo profile and essay from his years as a staff photographer for Look magazine; and there is a quality at the core of several, if not all, Kubrick films that hearkens back to magazine-style photojournalism. Kubrick uses the body language of the characters in relation to their space to both articulate character sensibility and development and their relationships with each other. The characters in Killer’s Kiss (1955) might be shadow puppets. The dialogue and character exposition range from the schematic to almost hilariously blunt to psycho-absurd; but, in almost perfect sync with gesture and movement, the film story holds us with its drive and urgency.

In Paths of Glory (1957), set against the backdrop of World War I, human conflict is plotted out against variously social, ceremonial, strategic and mechanical spaces. In the opening scene, set within the drawing room of a grand chateau, Kubrick choreographs one general cagily circling (and ensnaring) another in what amounts to a martial minuet, as they discuss a maneuver that will cost the lives of hundreds of their soldiers. The forthright Colonel Dax (Kirk Douglas) does not linger in this space—or any other—but, framed by barracks and trenches, moves relentlessly forward into a backtracking camera.

Breaking Lolita (1962) out of the head of its narrator, Humbert Humbert, involved similar cinematic choreography—counterpointing Humbert’s interior monologue with his various pas de deux and trois with Lolita, her mother Charlotte, and the enigmatic Clare Quilty. Here (as if the screenwriting services of Vladimir Nabokov were not enough), Kubrick was aided by another kind of cinematic trick: genius casting. In addition to Sue Lyon’s revelatory performance in the title role as an American suburban “nymphet,” and the note-perfect performances of James Mason and Shelley Winters in the roles of Humbert and Charlotte, Kubrick was afforded the services of another genius, Peter Sellers, as the chameleon Quilty. From Quilty’s disheveled mansion to suburban interiors and backyards, to the open road, to the revelation of the character of Lolita herself, Kubrick foregrounds frank yet guileless American corruption against a receding horizon of betrayed idealism and false (European) cultural pretensions.

Kubrick would deploy Sellers for another triple impersonation in Dr. Strangelove, or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964). Here, Kubrick shows us a ship of state turned ship of fools, a synoptic view of man’s fate rendered tragic-comically absurd. Sellers is variously angel/handmaiden to the incapacitated (as Mandrake), agent of inefficacy (as President Muffley), and agent of doom (Strangelove). In the Ken Adam-designed War Room with its halo of light bathing the circled desks and soaring raked walls with strategic maps tracking SAC deployments, as the world closes in on its masters, Muffley dissolves into the light, while Strangelove wheels around seemingly out of nowhere—an anti-Christ manifesting from the void—the same void through which Slim Pickens as Major Kong will ride his nuclear warhead to bright oblivion.

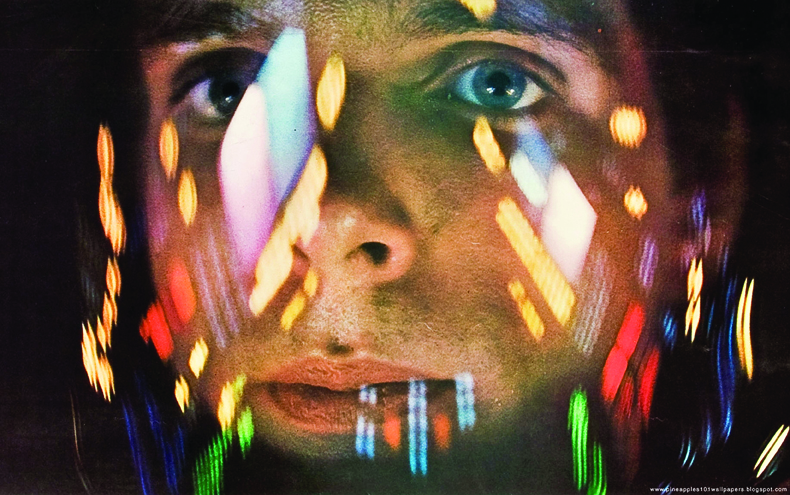

The troubled spaceship, “Discovery 1,” in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), under the stewardship of another dubious (and similarly constituted) trio, might be considered another kind of ship of fools. Here, within astonishingly realistic sets, including a rotating centrifuge, Kubrick documents the tasks and activities of his astronauts Poole (Gary Lockwood) and Bowman (Keir Dullea), including their interactions with the HAL-9000 computer (voiced by Douglas Rain) through which, in tandem with earth-based command operations, virtually all of the vessel’s functions are managed and run.

But within the arc of Kubrick’s Odyssey, which after all takes us back to the dawn of humankind and fast-forward (via “stargate”) to another sort of dawn, Discovery’s troubles amount to a sideshow—however elaborate and richly informative, critical to this particular dramaturgy of space.

In 2001, the human relationship to space—from the microscopic to the cosmic—would seem to be at the heart of the film’s subject matter. But more central to Kubrick’s concerns here are the ways humankind orders space, our extensions into space, and the attenuation of our relations to these extensions over time and distance—and by implication, to each other.

There is a break here, left unresolved by Bowman’s emergence into the Louis XVI-classical space of his observation chamber, his transfiguration via yet another vessel—the “amniotic” sac of the Star Child.

Some of these issues are foreshadowed in Kubrick’s earlier films: the inventory and ordering of human thought; the protocols seemingly dictated by mechanistic feedback. (E.g., in Strangelove, the operation of the Doomsday Machine; Muffley’s attempt to placate the Russian premier’s inebriated pouting at the protocols of the hotline: “Of course I like to say, ‘hello,’ Dimitri.”; Mandrake’s desperate attempt to tease out the return command code.) Kubrick would weigh these issues in another far more dystopic futuristic context in his film based on Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange (1971). More than Kubrick’s preceding (or later) films, the surrealistic visual style of Clockwork is identifiably of its time (though as always, Kubrick is ahead of the pack—consider that Scorcese’s Taxi Driver was released five years later). Here, a swinging welfare state incarnation of the U.K. (tailor-made for a Thatcherite campaign ad) is the backdrop for a counterculture of wanton gratification and sociopathic violence amongst a balkanized but empowered welfare class with time on its hands and vivid comic-book imaginations.

Without setting aside concerns central to his prior films, in Clockwork, Kubrick moves beyond a straightforward spatial choreography to a fluid and versatile style beautifully adapted to the post-Pop landscape that had evolved between the time Burgess published his novel and when filming began. In Clockwork, Kubrick has already leapt beyond that landscape to what we now recognize as Postmodernism. Its influence can be seen in everything from music video to Japanese anime to (in its lowest common mass-dilution) Apatovian freaks, geeks and superannuated lost boys.

Although Kubrick yearned to return to the “big canvas” of a historical picture, his difficulties financing a long-planned Napoleon project, turned him toward a more intimate novel set against the panorama of 18th-century Britain and Europe, William Thackeray’s Memoirs of Barry Lyndon, Esq. Here, Redmond Barry’s progress from Irish adventurer to baronial seat to forlorn exile unfolds against landscapes and interiors deliberately intended to evoke Gainsborough, Chardin and Menzel. Adapting lenses used by space discovery missions to cameras once used for background film, Kubrick shows us the world Barry sees and moves through—in natural light, the filtered daylight from the windows of high-ceilinged great halls, and candlelit drawing rooms. There are no feints or sideshows here. Kubrick has even substituted a narrator for Barry’s first-person voice. Instead, the pictures are allowed to tell the entire story—set magnificently to music by Bach, Mozart, and, most famously, the Handel D-minor Sarabande and Schubert E-flat piano trio. Music literally underscores what Kubrick commits and resigns us to—Barry’s quest for some purchase on his fate and his inexorable surrender to it.

Barry Lyndon is a pivotal moment in Kubrick’s career—as dark as its candlelit salons. In no other Kubrick film are we left with a comparable sense of the futility of human agency. Even Jack (Jack Nicholson) is ultimately recomposed into the “big picture”—repossessed by the world of the Overlook Hotel in The Shining (1980). Private Joker (Matthew Modine), the reluctant killer, survives and moves on, his humanity marginally intact, which, in the context of Full Metal Jacket (1987), is saying a lot.

LACMA’s Kubrick exhibition sprawls between the foyer and the adjoining plaza-level galleries of its Art of the Americas building, but has a resonance and coherence that accords with the issues and concerns that thread through these very distinct pictures. Walking between the installations built around various props, stills and transparencies, clips, documentation and paraphernalia, the viewer has the sense of moving between rooms marked by formative incident or heightened awareness—which is true to the experience of the films. Caught up in the dramatic and affective themes and motives of the individual films, we may be less conscious of what they present in their totality—which is nothing less than a history of late 20th-century consciousness.

S

-

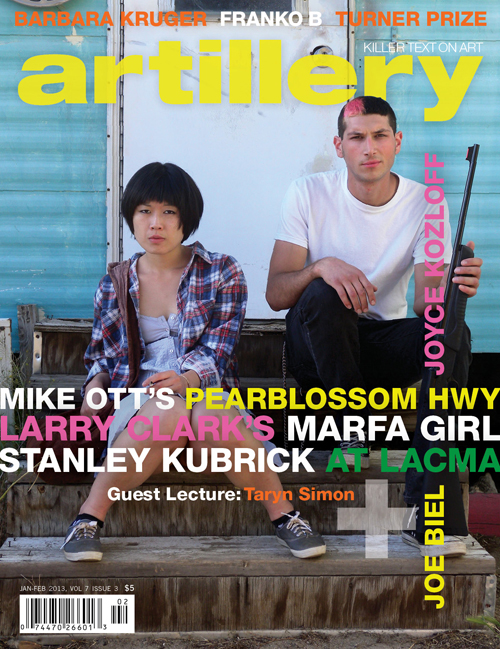

Editor’s Letter

Dear Readers,

In this issue of Artillery we’re featuring three stories on film. To tell you the truth, it wasn’t planned that way, but things just fell into place. Oddly enough, the three filmmakers represent a microcosm of hierarchical filmmaking. From acclaimed director Stanley Kubrick to indie filmmaker riding the crest, Mike Ott, with Larry Clark in the middle, a rebel artist finally getting his due with Best Film at the Rome Film Festival.

In this issue of Artillery we’re featuring three stories on film. To tell you the truth, it wasn’t planned that way, but things just fell into place. Oddly enough, the three filmmakers represent a microcosm of hierarchical filmmaking. From acclaimed director Stanley Kubrick to indie filmmaker riding the crest, Mike Ott, with Larry Clark in the middle, a rebel artist finally getting his due with Best Film at the Rome Film Festival.To give you a glimpse into the editorial world at Artillery, everything was filed and ready to go to the designer when I woke up to a string of emails congratulating Larry Clark for his triumph in Rome. I went straight to YouTube and watched his acceptance speech. Our contributor Luca Celada happened to be in Italy, and yes, he did attend the festival awards, and yes he did in fact see Clark’s film, Marfa Girl. What luck! And such an extra bonus that Luca can interpret the Italian translator, euphemizing her way around all of Clark’s profanity. Hilarious.

But wait. This is an art magazine! You might ask why do we have three articles about film? Actually, we’ve been writing about film since our first volume. Our regular column about esoteric DVDs on the current market, Bunker Vision by Skot Armstrong, has been in the magazine from day one. And we had a Film & Art issue during our first year.Most artists and art-lovers are very much into the cinema and probably secretly dream about making their own films. An artist who works with the camera often fantasizes about putting all those pictures together to make a movie. It’s a very natural progression. And that has been Clark’s experience, since he first made an impact with Tulsa, his seminal book of gritty black-and-white photography, in 1971. Artists who combine imagery with narrative are natural candidates for having some kind of film in their repertoire—at the very least, one black-and-white Super 8 short.

Clearly, filmmaking is part of the “art” world. Many visual artists have worked in film: Mike Kelley, Paul McCarthy, Sharon Lockhart and Marnie Weber are a few LA artists that come to mind. But their films fall more into the category of experimental filmmaking with a very loose or nonexistent narrative. In other words, these films are not hot prospects for success in the commercial movie industry. Nevertheless, they are artists making films.

That said, the film industry per se doesn’t really interest me as material for Artillery. But here we are in Hollywood, and it just sort of creeps into the art world. We all wish Hollywood would pay a little more attention to the artists out there (as in taking advantage of—and paying for—the preeminent art Los Angeles has to offer). It’s pretty obvious how very little the film world knows or cares about how the art world really works. We see evidence of this whenever a movie attempts to portray an artist or the gallery system.

But the three film stories in this issue are about filmmakers who are artists with unique visions and aesthetics. And whether you’re making a film, writing a book, directing a TV sitcom or telling a joke, if it’s any good, if it’s creative, if it’s something you’ve never seen before, then it’s probably art. And that’s why it’s in Artillery.

In this issue of Artillery we’re featuring three stories on film. To tell you the truth, it wasn’t planned that way, but things just fell into place. Oddly enough, the three filmmakers represent a microcosm of hierarchical filmmaking. From acclaimed director Stanley Kubrick to indie filmmaker riding the crest, Mike Ott, with Larry Clark in the middle, a rebel artist finally getting his due with Best Film at the Rome Film Festival.

In this issue of Artillery we’re featuring three stories on film. To tell you the truth, it wasn’t planned that way, but things just fell into place. Oddly enough, the three filmmakers represent a microcosm of hierarchical filmmaking. From acclaimed director Stanley Kubrick to indie filmmaker riding the crest, Mike Ott, with Larry Clark in the middle, a rebel artist finally getting his due with Best Film at the Rome Film Festival.