Your cart is currently empty!

Tag: Amy Sherald

-

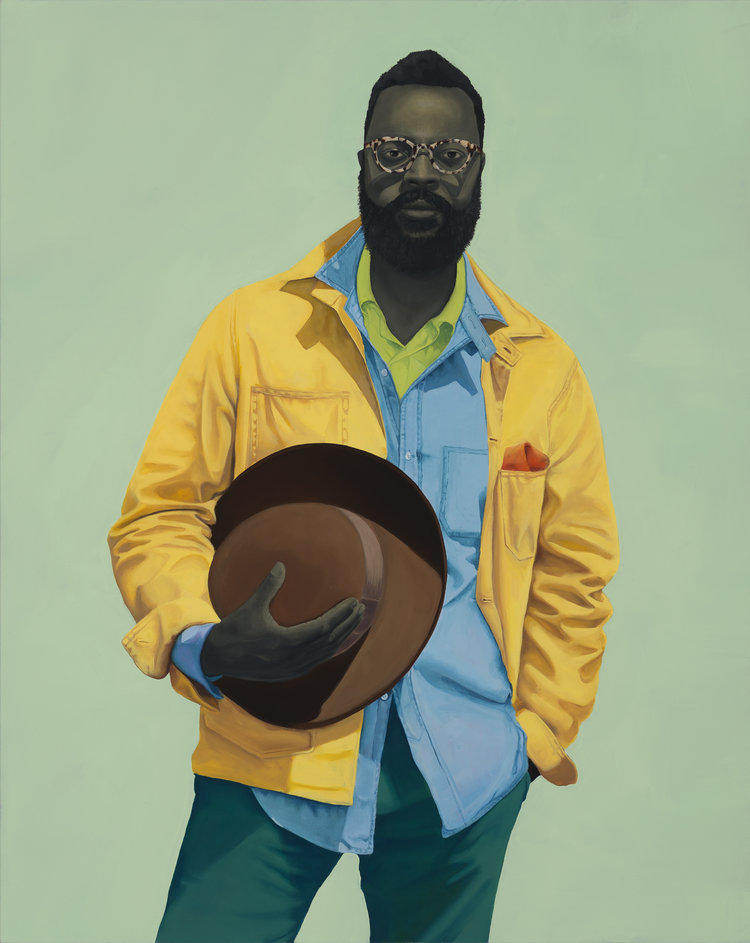

Pick of the Week: Amy Sherald

Hauser & WirthThe Impressionists, at the end of the 19th century, turned away from traditional muses and academies and became chroniclers of their contemporary era. They were described as flaneurs, self-styled spectators of modern life and people in leisure. But throughout their work – and throughout the art historical canon – there is a notable exception: people of color. Even the few that were depicted were ignored for decades, such as Edouard Manet’s Portrait of Laure, which was originally named La Négresse, a reductive title which obfuscates any true identity. This historical mistreatment is why Amy Sherald’s first solo west coast show, “The Great American Fact,” is so vital.

Sherald’s show illustrates Black Americans at leisure in Sherald’s signature style. Whether they’re posing with surfboards or leaning on bicycles, the monochromatic models exude a powerful peacefulness amid vibrant colors. Unlike some of her more famous subjects, like Michelle Obama or the late Breonna Taylor, the figures of “The Great American Fact” are intentionally ordinary. They could be anyone, a fact reinforced by their gray-scaled skin – there is not even an emphasis on the color or shade of their skin, but rather their beauty as human beings.

This is not to say that Sherald treats these people as ordinary. In As American as apple pie (2020), two figures stand in front of a ranch-style home and a vintage Cadillac. The woman wears all hot pink with a beehive haircut, the man cuts a spitting image of the iconic James Dean. It is as Americana as you could imagine, yet features two people whom America forgot – but were always there.

Sherald’s layers of nuance seemingly never end. In a portrait of a young woman entitled Hope is a thing with feathers (2020), Sherald emblazons the too frequently violent arena of a Black woman’s body with the universal symbol of peace: a dove. The relaxed repose of the model, arms loose at her side and face neutral, underscore that resilient vulnerability which is necessary for peace. To borrow from the Dickinson poem which Sherald references in the title, her work “sings the tune without words, and never stops at all.”

Hauser & Wirth

901 E 3rd Street, LA, CA, 90013

Thru June 6, 2021; Appointment Only -

Face to Face: Los Angeles Collects Portraiture

As noted in an Artillery Pick quite recently, portraiture is the oldest form of ‘identity art’, and moreover, representation itself. It is ‘naming’ in the largest sense – placing, identifying, classifying, narrating, and implicitly conceptualizing, though without explanation. In other words, at its most successful, it gives us some sense of what it means to be alive in a specific time and place. To the extent that the classifying impulse has often functioned as an aspect of colonialism, we can be grateful that Face to Face, the California African American Museum’s current show of portraiture, is liberated from that taint. The current show is bracing both in terms of its chronological and stylistic range, and its clear reflection of L.A. collectors’ on-going engagement with this work. But what is particularly fascinating is the extent to which over the course of that liberation from the vestiges of colonialism, African-American artists have transformed the classifying impulse into something larger, more broadly conceptual and frankly subversive – e.g., the performative aspect of work by Mickalene Thomas and Tschabalala Self, or crossing the representational threshold into the domain of fiction, as in the ‘imagined’ (or is it?) portraiture of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. The iconic ‘reversal’ (or perhaps more literally here, ‘inversion’) is another strategy represented here. It’s the polar-opposite of, say, Kehinde Wiley (who is also represented here – in one of his more interesting paintings), where the iconic aspect of a subject is referenced and simultaneously subverted. Titus Kaphar does this quite literally in his 2014 Jerome VII, where the lower half of the subject’s head, floating in its gold leafed field, is enshrouded by gold-flecked tar. Even the most straightforward and conventional of the portraits evince a sense of flux, the conditional (and perhaps aspirational) – always moving towards another place, another way of being. In this relatively compact exhibition, curators Naima J. Keith and Diana Nawi have in turn offered viewers another way of seeing that process play out.

California African American Museum (CAAM)

600 State Drive – Exposition Park

Los Angeles, CA 90037

Show runs thru October 8, 2017