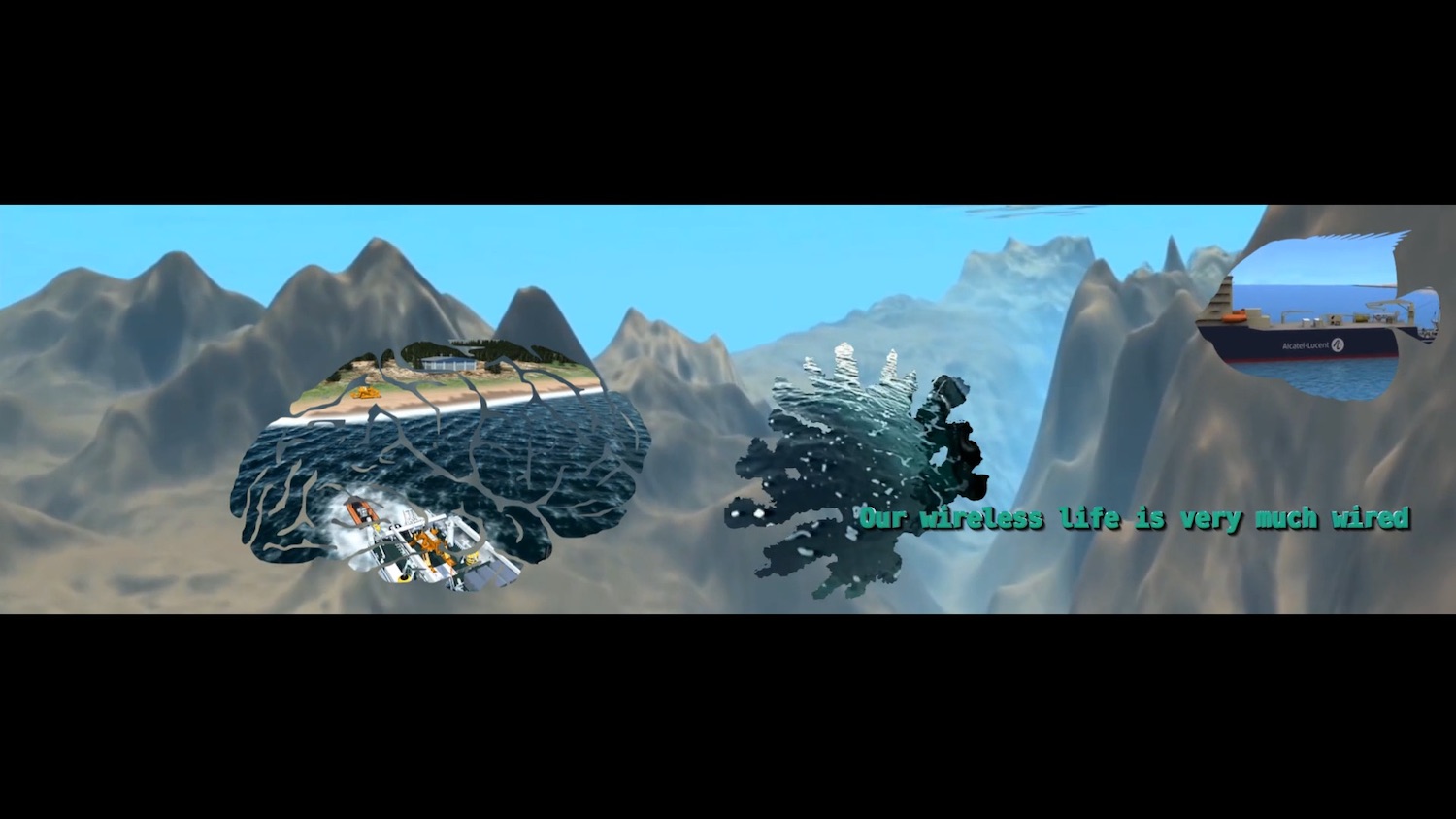

The digital is an arbitrary category. In everyday speech, it is sometimes used as an opposition to the material: a digital copy, artwork or exhibition versus a material one. The digital is presented as something existing outside of the material realm and the history and politics thereof; an apolitical utopia that does not hold the same accountability as the “real world.” However, the line between the digital and the so-called real is constantly blurred if it ever existed in the first place. “Our wireless life is very much wired,” as Guinea-based artist Tabita Rezaire points out in her video work Deep Down Tidal (2017), in which she explores the racialized materiality of the internet.

Galleries’ and museums’ use of online exhibition platforms and the digitization of museum collections have been accelerated over the past couple of years by technological advancements as well as lockdowns that have made accessing “regular,” in-person shows difficult and at times even impossible. In many instances, the digitization of content has made it more accessible across varying access needs and financial situations—a much-welcomed change to increasingly privatized and commercialized art institutions. Another recent digital tendency within the art world is NFTs. Although they have existed since 2014, non-fungible tokens (NFT) became commonly known last year when an NFT artwork was sold for as much as $91.8 million, gaining international media attention. Surrounding both digital exhibitions, collections and artworks, such as NFTs, is a discourse of immateriality. However, critics have also pointed out how NFTs specifically—which rely on blockchain technology—are polluting the atmosphere due to their high electricity use, as they require extensive “mining” done by computers.

The smooth interface and minimal hardware that the user engages with—be it a smartphone, laptop or tablet—may create the illusion that whatever takes place digitally has a minimal physical presence and impact but in fact it is estimated by the French Environment and Energy Management Agency that digital technology consumes 10% of the world’s electricity, and that if the internet was a country, it would be the third largest consumer of electricity, following China and the US. The internet is created in fiber optic cables, lying on the seabed. Around 60% of the world’s population is counted as active users of the internet but many don’t realize the physical aspects of this quotidian phenomenon.

Stills from Tabita Rezaire, Deep Down Tidal, 2017, video, 18.44. Text on images reading ‘Internet is not in the clouds’, ‘it lies on the sea floor’.

Deep Down Tidal

In the opening scene of Tabita Rezaire’s video work Deep Down Tidal, a person floating on a cloud in outer space is having an amicable phone conversation stating they have been banned from Facebook for posting that white people should give them back their land. This comedic opening portrays an absurd reality of political censorship of marginalized people on social media. The songs playing from the phone speakers are in various languages and originate from different parts of the globe, referencing the international nature of the internet. The video, which is a collage of popular cultural references, Google searches, satellite images, the phone conversation, a voice-over and more, explores the connection between the trans-Atlantic slave trade and the internet; the racist history and present of the internet and its materiality.

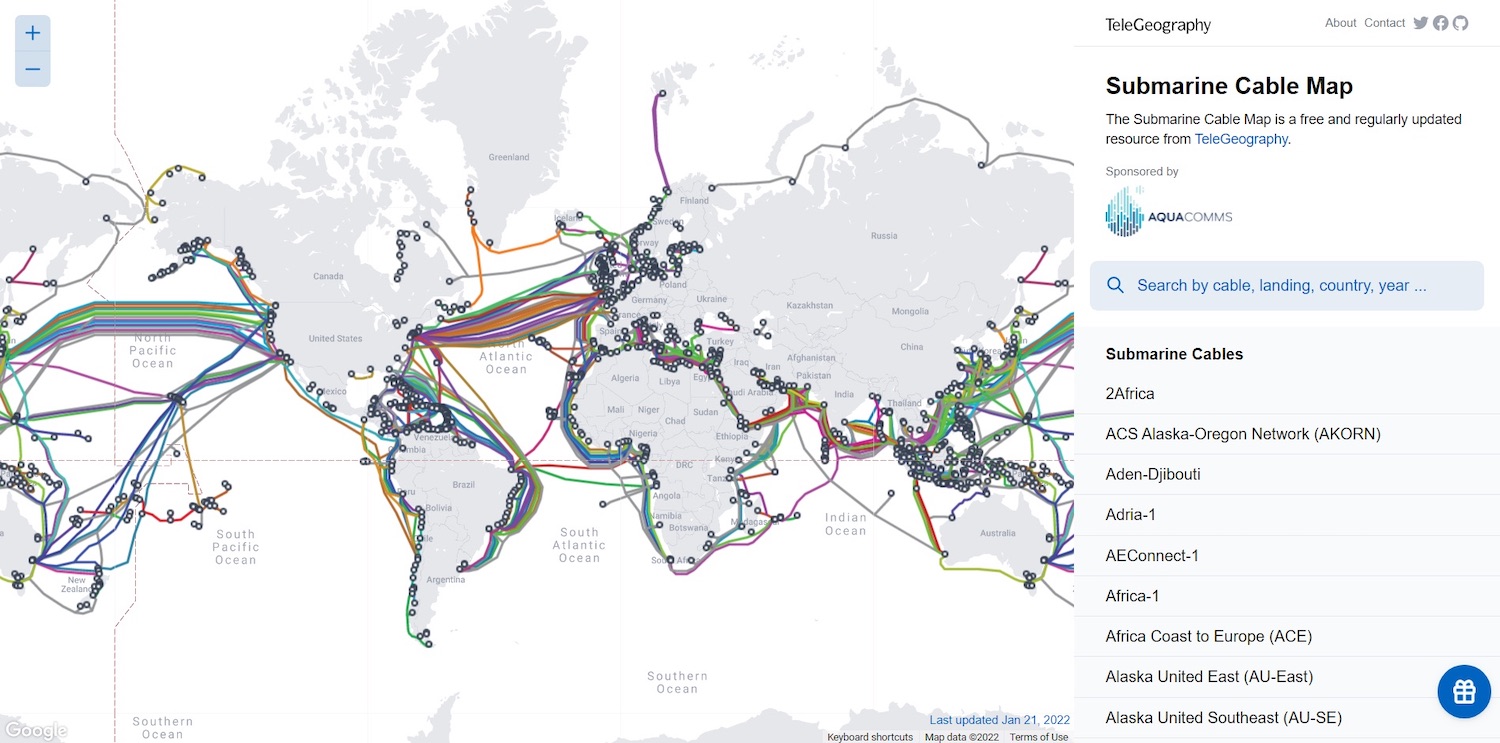

Rezaire’s interdisciplinary practice is focused on healing through speculative, scientific imaginaries, and spans video, installation and performance lectures. She envisions organic, electronic and spiritual network sciences as healing technologies. Deep Down Tidal deals with the history and politics of the materiality of the internet. In the video, Rezaire mentions the trans-Atlantic telegraph cable laid between the United Kingdom and the United States in 1858, following the colonial shipping routes and colonial relationship between the two countries. Today, electric fiber cables lying on the seabed make up 99% of the world’s internet. The cables, thick as a garden hose, are laid out by special cable ships. On the website Submarine Cable Map, one can trace the hundreds of undersea cables that make up the internet and information including its length and its owners. The cables are generally owned by private companies such as Google and Meta (Facebook), therefore governed by private, corporate interests. Rezaire refers to the cables as “the hardware of the new imperialism,” speaking of how the internet is used to uphold already existing colonial power dynamics between the different countries. Naming the cables “hardware,” Rezaire acknowledges how these cables are the very material of the worldwide web. She plays with the notion of the internet as a “cloud” and the implication that it is non-terrestrial while explaining its underwater reality. By crosscutting between scenes from outer space and the sea, she hints at the connection between the two and the common alienation from both. “Internet is not in the clouds, it lies on the sea floor,” she says, but it may well be that the cables are as hidden undersea as they would have been in the sky.

Screenshot of Submarine Cable Map showing the networks of undersea internet cables https://www.submarinecablemap.com/

Alienation of Labor

The immateriality, or rather invisibility, of the internet is part of the general hyper-alienation of labor that characterizes the 20th and 21st century. “Cables are spaces where labor, knowledge and capital are sunk into the sea, ” Rezaire says. The undersea cables are not invisible to the workers who make them or lay them down, or to the marine life that is invaded by these cables. But the average user of the internet, who may be using the internet daily, has never seen underwater network cables and may very well not even be aware of their existence. The ignorance of the users of the internet allows for the continuation of a discourse of the internet as a space outside of the material realm and its consequences—be it on climate change or racism or workers’ rights. The alienation from the internet is in many ways like any other kind of disconnect between worker, consumer and product—as with food, textiles and so on. However, the relative novelty of the internet and the lack of technical understanding of its workings may be intensifying the already exacerbated sensation of detachment. By telling the story of undersea internet cables, Rezaire creates an opportunity for a critical engagement with what to many is a common yet arbitrary realm; the digital.

Still from Tabita Rezaire, Deep Down Tidal, 2017, video, 18.44. Text on image reading ‘Our wireless life is very much wired’.

The digitalization of certain aspects of society, including aspects of the art world, has in many ways increased accessibility and created new opportunities for creative exploration. The internet has changed the world and holds vast potential to continue to do so—within as well as outside of the art world. There is no point in writing off what we may refer to as “the digital,” but it’s worth asking what it is that we are actually referring to. Complex interaction with the means of the internet and the digital at large requires a more specific, subtle language that may yet to be both invented and implemented. Familiarizing ourselves with the specifics of the digital and its histories, through art, education and more, renders possible a nuanced participation with the digital and its potentials as well as with its material consequences and working conditions. In order to do so, we must not think of the digital in opposition to the material realm but rather as an integral part of it, including its politics, histories and complexities. The digital must not be regarded as a utopian or dystopian other, but as a continuation of the layered, intertwined worlds that we inhabit. Our wireless life is very much wired.