“What are we looking at?” You hear that (usually rhetorical) question a lot in art galleries and design houses – also in accounting firms, screening rooms, at construction sites, and (really) business meetings of any kind – frequently spoken with some impatience. (We’re always in a hurry here, even as we’re telling ourselves to slow down – which is what this question is actually asking for permission to do.) It is understood that what is referred to here is a presentation, or representation of the actuality, the thing, what we all agree to agree is the reality. How we may think about that agreed-upon actuality or reality becomes a matter of both methodology and attitude. (As opposed to ‘ideology’ – which implies another constellation altogether of concepts, precepts, ideas, notions and theories well beyond ‘bias’.)

It’s real—getting down to the physical aspects of the process. Our eyesight, nerve connections, cognitive and intellectual skills are all in play even before we think about how to think about it. Everything factors in: the lighting, where we sit, how we stand, how we slept, what we dreamed, what we just ate, whether we’re sufficiently hydrated or caffeinated; and then there’s everything else. Laughing in unison at the same screen gag (wondering when that will ever happen again)—are we ever really laughing at the same joke?

There is a forensic aspect to a great deal of Susan Silton’s work, from the most conceptually abstract or textually grounded to the operatic, almost disquietingly close to the operations of criminal justice—where relatively neutral terms often carry grave implications. The foundational material of the work carries a weight similar to the ‘information’ that precedes a complaint or formal indictment. It may be only partially coincidental that at least two of her most recent works were effectively indictments (of the Trump administration’s willful endangerment of public safety; news and information media’s passive normalizing of violated ethical norms and the assault on constitutional democracy across the political landscape). Silton steps back here—or to be more precise, places us in what is both a neutral space, the convergent space of shared human language and agreed-upon perceptual field or actuality, and a kind of secular-sacred space that, in the terms of the most counter-intuitive theories of perception may, in Möbius-twist fashion, represent no mutually agreed-upon reality whatsoever.

There is a forensic aspect to a great deal of Susan Silton’s work, from the most conceptually abstract or textually grounded to the operatic, almost disquietingly close to the operations of criminal justice—where relatively neutral terms often carry grave implications. The foundational material of the work carries a weight similar to the ‘information’ that precedes a complaint or formal indictment. It may be only partially coincidental that at least two of her most recent works were effectively indictments (of the Trump administration’s willful endangerment of public safety; news and information media’s passive normalizing of violated ethical norms and the assault on constitutional democracy across the political landscape). Silton steps back here—or to be more precise, places us in what is both a neutral space, the convergent space of shared human language and agreed-upon perceptual field or actuality, and a kind of secular-sacred space that, in the terms of the most counter-intuitive theories of perception may, in Möbius-twist fashion, represent no mutually agreed-upon reality whatsoever.

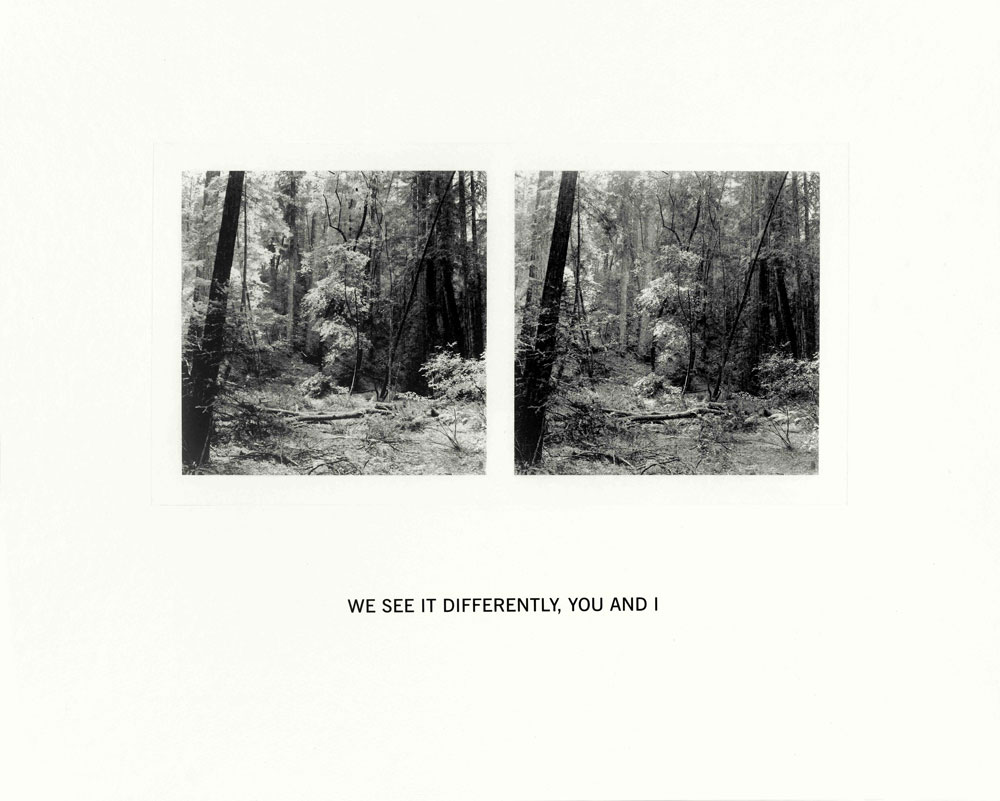

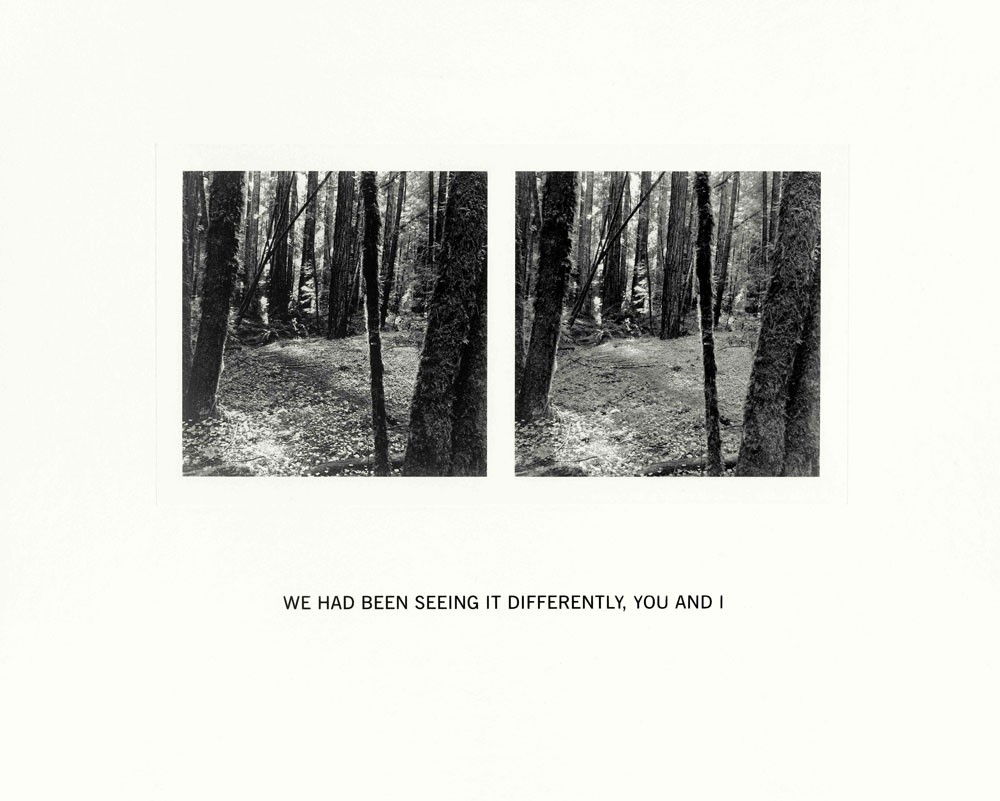

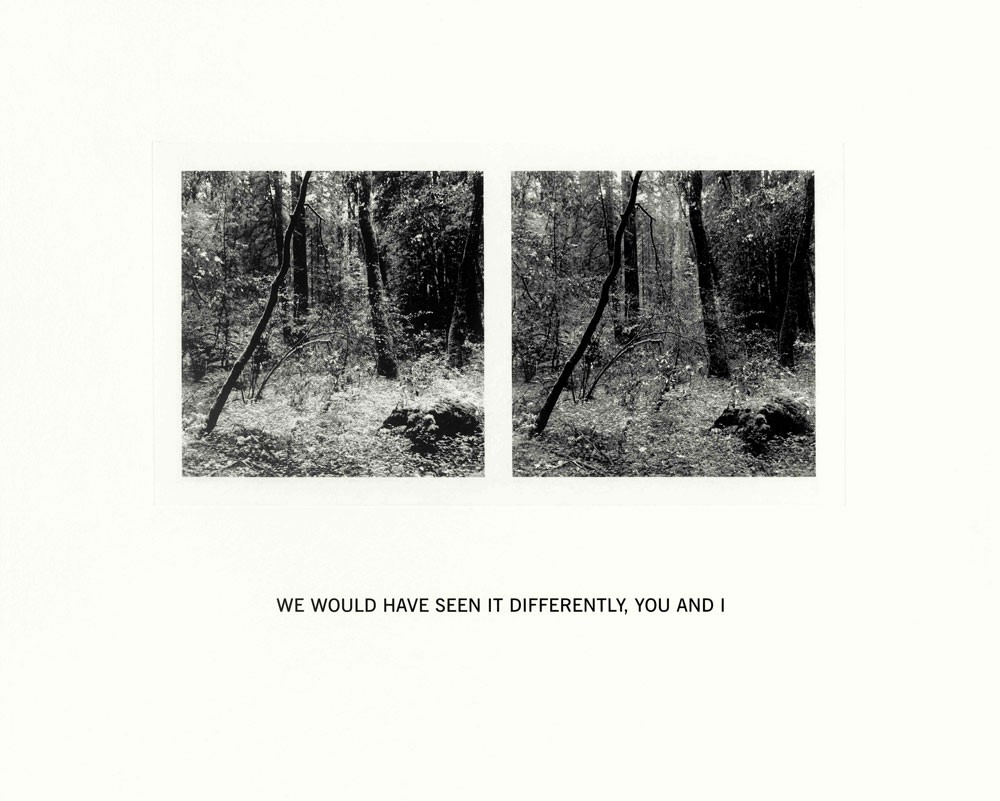

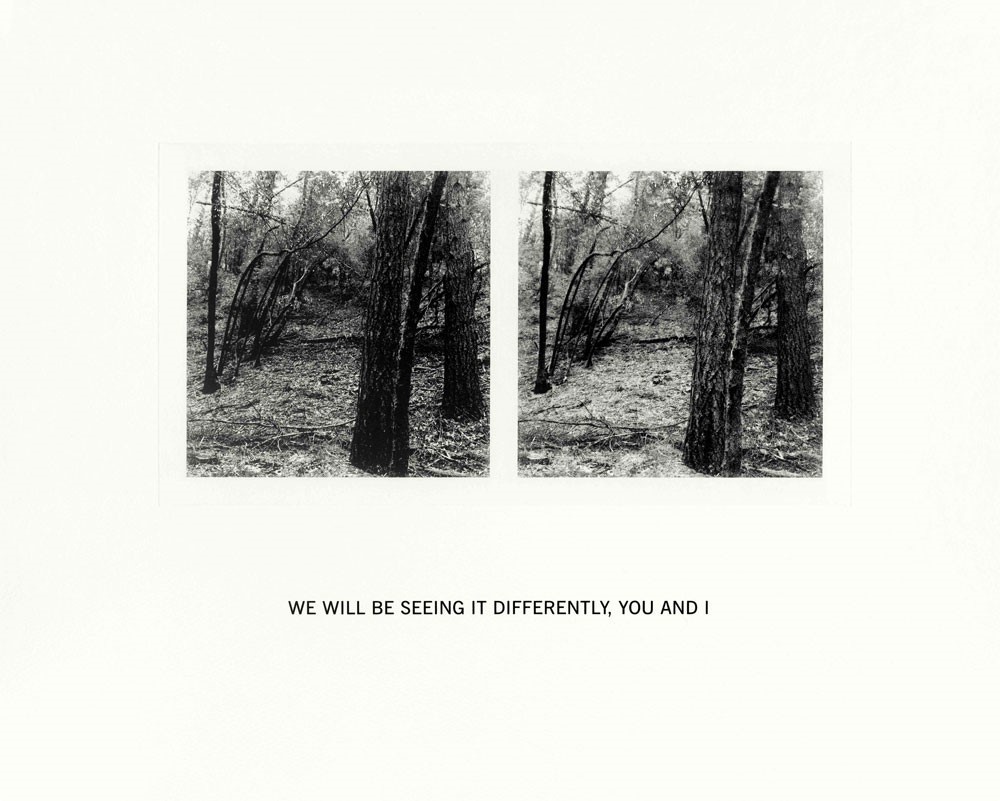

Silton presents 16 photo-etchings here, with accompanying texts that constitute what might be called a single ‘theme-and-conjugations’ work. The photographs were taken along various trails and partial clearings in the Armstrong Redwoods State Natural Reserve, majestically wooded with many ancient sequoias rising amid the foliage—fortuitously taken before many of the same trees were damaged or destroyed in the LNU Lightning Complex fires of only a year ago. Each print presents a pair of identical or nearly identical images of sections of the preserve. Beneath each pair is a variation of the statement, “We see it differently, you and I.”—what one might consider a kind of neutral opening engagement in a dialogue, preliminary to a dialectic that might expose more fundamental differences between two distinct viewpoints or perspectives.

That neutrality is preserved as we move through the images, which take their meandering course through sections of the preserve, at points pushing us deeper into dense stands of trees, viewed from various distances—which in turn ask for the viewer’s judgment as to actual depth or distance (we may not only be seeing it ‘differently’, but with varying degrees of accuracy)—or pulling us back or off trail to take in a slightly more variegated view of contrasting elements (the contrast between ancient trees and younger growth), or into shallow clearings which may give a sense of surround or overlook. It is not accidental that each of these ‘turns’, these moments, offer viewers opportunities to judge their own impressions of the landscape elements.

Silton has altered the views by various filters, as if to mimic the effects of varying sunlight—morning light giving way to more intense afternoon glares (further dependent upon the density of forest growth), and softening as evening approaches. The views are always going to change, depending upon the time of viewing, our transitions from one part of the wood to another, variable angles of illumination—and those underlying foundational differences of cognition, nerve/muscle capacity, comparative experiential perspectives, and those pre-dispositions imprinted in our DNA. (“Did I tell you about the filter on my sunglasses?” “Oh yeah?—mine are polarized, too.”) We will be seeing it differently, you and I.

Silton has altered the views by various filters, as if to mimic the effects of varying sunlight—morning light giving way to more intense afternoon glares (further dependent upon the density of forest growth), and softening as evening approaches. The views are always going to change, depending upon the time of viewing, our transitions from one part of the wood to another, variable angles of illumination—and those underlying foundational differences of cognition, nerve/muscle capacity, comparative experiential perspectives, and those pre-dispositions imprinted in our DNA. (“Did I tell you about the filter on my sunglasses?” “Oh yeah?—mine are polarized, too.”) We will be seeing it differently, you and I.

The texts present the statement, “We see it differently, you and I.”, in all sixteen of its conjugations, present, past and future, including progressive and conditional tenses. The progressive and conditional are critical in this—what amounts to a morphology of both word and image. In language, syntax is what generally conveys intent and viewpoint. But this goes to a more fundamental structural distinction—one related to both formation and inflection—which applies as much to image and perception as it does to their linguistic formulations. Silton unfurls a precisely cadenced meander here fusing formation and inflection of our perceptions and observations. There is a continuity from one ‘tense’, one view or ‘condition’ to another; and also a provisionality. Each view or perspective, is shadowed (or illuminated), by what has gone before, what is anticipated, what has been pre-determined—irrespective of the veracity or verifiability of those determinations.

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose, one might say, as one régime gives way to another. But that wasn’t the tune we were singing this past January. In fact, everything changes all the time, and sometimes profoundly. There are repeating cycles, it’s true—but some of those cycles are impactful and progressive, and effect profoundly different levels of change, some of them radical, all of them consequential. To reiterate: the straight ‘information’ is not always neutral or innocuous. The conjugations and transitions here also illuminate a metamorphosis—or certainly its potentiality. It is sobering to recall that major portions of this treasured preserve were destroyed or permanently damaged in last year’s fires. We are altering the view—however provisionally—by our view, by our presence—and certainly our relationship to the place(s) described.

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose, one might say, as one régime gives way to another. But that wasn’t the tune we were singing this past January. In fact, everything changes all the time, and sometimes profoundly. There are repeating cycles, it’s true—but some of those cycles are impactful and progressive, and effect profoundly different levels of change, some of them radical, all of them consequential. To reiterate: the straight ‘information’ is not always neutral or innocuous. The conjugations and transitions here also illuminate a metamorphosis—or certainly its potentiality. It is sobering to recall that major portions of this treasured preserve were destroyed or permanently damaged in last year’s fires. We are altering the view—however provisionally—by our view, by our presence—and certainly our relationship to the place(s) described.

The factual complexities of the actualities and conditions are compressed here—the series is, after all, about impressions and images and their conditional description or iteration. The artist effectively turns the folio over to the viewer as if to propose a transfer of agency. Silton in fact asked the writer, Dana Johnson (In the Not Quite Dark), to author a short story to accompany the suite of image and text pairings—which emphasized durational aspects of an alternately progressive and conditional metamorphosis; also their ambiguity. The story could be said to leave the reader (and certainly its characters) ‘hanging’; and so has Silton—relinquishing ‘authorship’ (paraphrasing the words of another artist whose work has taken him into natural, albeit damaged, environments) and ‘passing the baton’ to her viewers—or to continue the paraphrase, “citizen stakeholders”—which WE are. The elegance of Silton’s theme-and-variation suite allows us to take cool appraisal of those stakes, but this is a conversation with a long and resonant sustain. “The process of restoration begins with a walk,” Tim Collins wrote in Conversations in the Rust Belt (cited in Sue Spaid’s superb catalogue for the 2002 Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center exhibition Ecovention)—and so it has here.