The photographic tableaux of Los Angeles–based Parisian transplant Reine Paradis evoke an ambiguity of place. The central focal point of each is a solo figure, played by Paradis, typically costumed in an A-line mini or similarly chic garment fashioned from transparent, tinted PVC; she is most often posed humorously or awkwardly—sometimes, heroically—in an iconic landscape, accompanied at times by sculptural origami animals that she holds on a leash (Elefanto, 2018), or an eerily childlike doll that appears to hold her hand (Crocodyle, 2016). Yet none of her works betray their locale; instead, they are stages for the whimsical fictions Paradis creates.

In L’envol (2016), she balances perilously along the cylindrical edge of a blindingly white water tower against an impossibly intense blue sky—a kind of ultramarine-phthalo-Prussian-blue mix that resembles International Yves Klein Blue—a detail that offers a perspective on Paradis as a feminist version of the dramaturgical modernist: think of Klein’s leap into the void. Instead of being dragged through pigment and bodily imprinted onto canvas, Paradis is the master of ceremonies, even when she is sprawled on a putting green (Moongolf, 2016).

Moongolf, 2016, archival pigment print, 60 x 42 inches (edition of 3), courtesy of Avenue des Arts.

Her photographic tableaux begin as scenarios that come to her as “visions,” Paradis explains during a visit to the South LA studio she shares with her husband, filmmaker Carl Lindstrom. Paradis records these first as “maquettes”—rough drawings akin to storyboards. They are fully realized as photographic tableaux, complete with props that she builds herself, and costumes she makes, at times with help from the upholsterers and furniture makers in the studios adjacent to hers, and they originate in her memories of make-believe scenarios acted out with her sister during their childhood in rural Southwestern France.

In the late 1980s Paradis’ artist parents fell in love with the region and relocated from the Antibes to the remote hamlet of Bilhac. “It’s not even a village, it’s like a hameau. You have a church, a few houses, but you have to drive to get to the next village,” Paradis says.

She recently returned to Bilhac with Lindstrom to shoot footage for a documentary. “I recognize similarities with my images and this place where I grew up,” she says. “There are so many things…for example, the empty pool [evoked in Empty Pool (2016) in her “Jungle” series].” She and her sister would often play in an empty pool adjacent to their property. “I didn’t really think about those things when I was creating the images.”

Empty Pool (2016). Archival pigment print, 60 x 42 inches (edition of 3). Courtesy of Avenue des Arts.

“My main inspiration is the location first,” she says. “And the light in LA is very different from the light I was used to in Europe… I shoot around midday. It’s always super-intense, very bright. I’m of course inspired by the colors that I use. They are one of the main focuses of my work. But everything is equally important,” she insists.

“Midnight,” her recent exhibition at Avenue des Arts in downtown LA, featured a new series of photo-tableaux that continues where previous series left off, along with excerpts from the documentary she and Lindstrom are working on, and an installation: a gold-painted pineapple, suspended on a filament, rotated slowly as it was videoed and simultaneously projected through a piece of lime-green Plexiglas cut into a graphic shape representing a pineapple. The image—a pineapple rotating over a rotating pineapple—was “rad,” according to one attendee overheard at the opening.

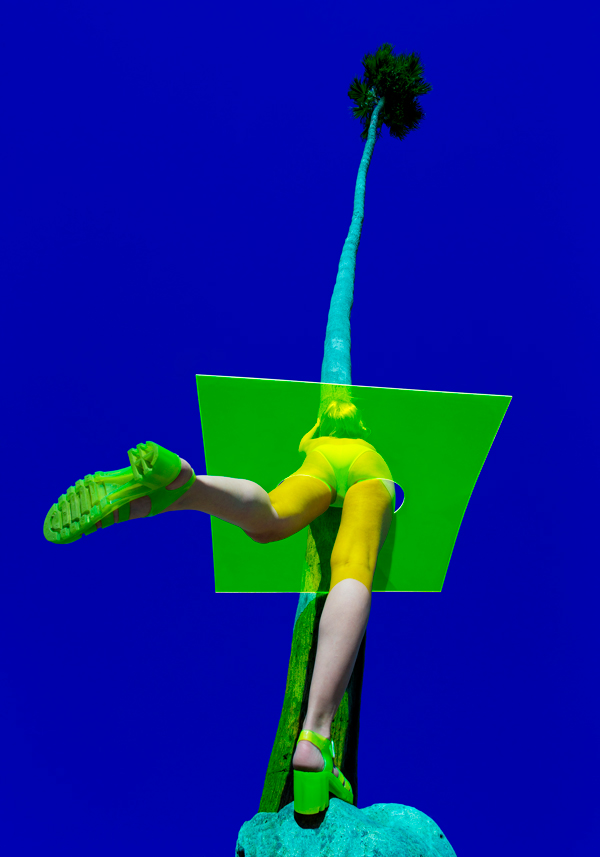

Palmsquare, 2018, archival pigment print, 90 x 63 in.; both editions of 3, courtesy of Avenue des Arts.

Paradis’ works engage in a kind of myth-making in which Paradis is herself both the author and subject. Some time ago—it’s not entirely clear when—the artist abandoned her patronymic surname in favor of something more… idyllic. But another cultural signpost is layered within and behind the surreal landscapes in which Paradis is the sole protagonist. In some works, she engages in light-hearted physical humor, sprawling, legs outstretched (Palmsquare, 2018). These evoke moments from the French auteur Jacques Tati’s series of films featuring the slightly befuddled Monsieur Hulot. It’s a source that Paradis acknowledges: “It’s not my inspiration, but it’s true. I had a friend who told me this too.” But Paradis’ cool aesthete takes Tati’s mildly amused cultural critique in a different direction. The sleek lines, primary colors and chic costuming are signifiers of modern sophistication, but the images are fantasy worlds that hold the promise of escape.