The legendarily expressive artist Louise Bourgeois said that the goal of her practice was “to give meaning and shape to frustration and suffering.” This meaning and shaping are potent at The Museum of Modern Art’s Louise Bourgeois: An Unfolding Portrait, a retrospective organized by chief curator emerita of prints and illustrated books Deborah Wye. The exhibition spans Bourgeois’s graphics, prints, drawings, paintings, and sculptures, and pays unique attention to process and the subtle evolutions in her work.

Bourgeois did not formally identify with the Surrealist movement, but held a profound focus on excavating the unconscious — she attested that much of her practice was rooted in a childhood discovery that her father was having an affair with her governess. This fixation could have easily remained a psychoanalysis-cliche, but Bourgeois’ brazen confrontation of pain rigorous self-interrogation gave way to a profoundly compelling body of work. As David Salle at The New York Review of Books writes, “One way to think about Bourgeois’s art is to imagine Surrealism, that most adolescent as well as female-objectifying of art movements, retooled by a grown-up woman.”

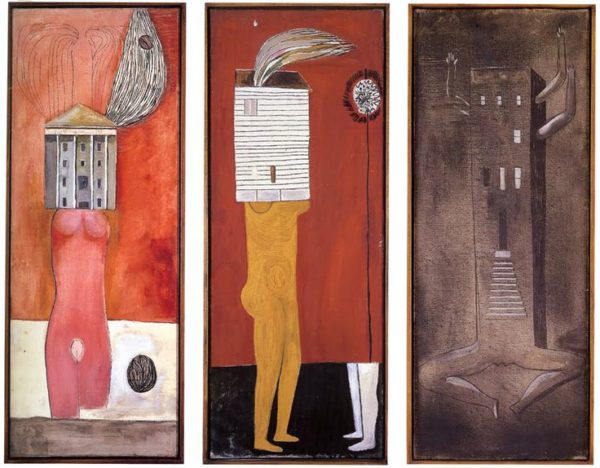

Trauma is formational in Bourgeois’ relationship to the body, which she treats as the site of suffering, but also transcendence. The body, like the mind, is something that can be controlled and manipulated to give way to something both beautiful and the grotesque. In the Femme Maison series (translated from the French as “housewife”), the faces and bodies of female figures have been replaced by architectural structures.

Femme Maison series

A common feminist interpretation of the Femme Maison women focuses on their abolition of self when subjected to the house structure, but Bourgeois was hesitant to call her work feminist, and once said that the issues her work grapples with are “pre-gender.” Regardless, she attacks the objectification of the female body with aggression, and also seems to have taken some pleasure in dissecting the male form. In a photograph by Robert Mapplethorpe that was taken for her first retrospective of the Museum of Modern Art in 1982 (also organized by Wye), Bourgeois holds a giant disembodied phallus, sporting a monkey fur coat and a mischievous grin, bringing to mind the many paintings of a slightly-smirking Salome. MoMA used the photo for the cover of the catalog, but cropped it to a headshot, eliminating the phallus.

Spider (Cell), 1997. Steel, tapestry, wood, glass, fabric, rubber, silver, gold, and bone. Collection The Easton Foundation, New York. © 2017

Bourgeois is perhaps best known for her sculptures of spiders, which are both menacing and protective: at the MoMA, her 1997 piece Spider (Cell), the spider acts as an enclosure with a chair seemingly for the viewer to sit in to be sheltered from the outside world. Bourgeois explains:

“The Spider is an ode to my mother. She was my best friend. Like a spider, my mother was a weaver. My family was in the business of tapestry restoration, and my mother was in charge of the workshop. Like spiders, my mother was very clever. Spiders are friendly presences that eat mosquitoes. We know that mosquitoes spread diseases and are therefore unwanted. So, spiders are helpful and protective, just like my mother.”

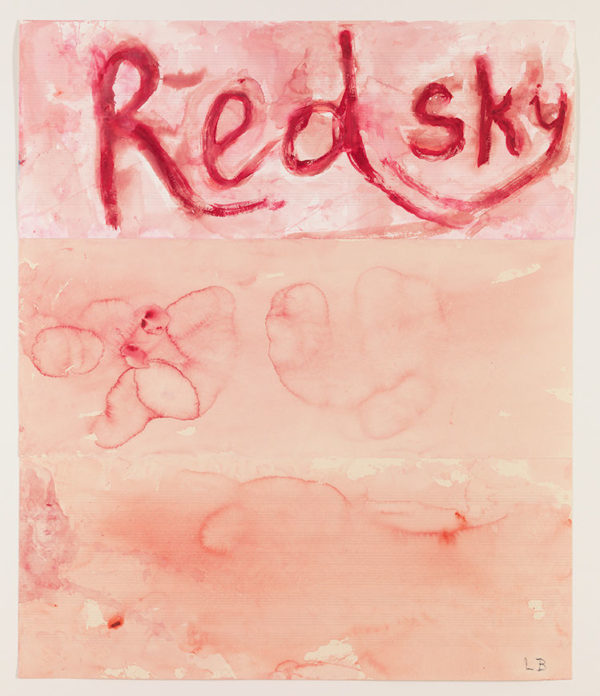

David Salle is also apt to note that the canon of male artists post-Da Vinci is thoroughly lacking in works that address the body from the inside. Bourgeois does this with incredible directness, and it might be her most unique contribution as an artist. “The Red Sky,” the Bourgeois exhibition currently at Hauser & Wirth in Los Angeles, displays her fascination with blood. To Bourgeois, pain was red. She said red represented “the intensity of the emotions involved” in her work — blood, organs, capillaries – and added that the “depth of depression is measured by your attraction to red.”

© The Easton Foundation/VAGA, NY Courtesy Hauser & Wirth Photo: Ben Shiff

The exhibition features multi-panel works of conjoined sheets that link landscapes with the functions of the body and emotions. Her skies are not blue and serene, but red and tumultuous. While the Femme Maison series gestures toward a structure asserting itself over a woman, with her skies, Bourgeois asserts her own inner unrest over the natural world.

The Hauser & Wirth exhibition also displays her mastery of linking text to images, and incorporates lines from psychoanalytic texts and her own meticulous notebooks. In “Have a Little Courage,” created one year before her death in 2010, she interperced the following words among lightly sketched and painted forms that are quite tuned to one another:

“Dizzy / Spells // Beheaded / jilted / unprotected / slipped / and / could not get up // when fear / becomes conscious // watch out / and / Have a little / Courage”

The Red Sky runs at Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles, through May 20.