The art world has been revisiting issues of identity and identity politics in recent months (see, e.g., the current issue of ArtForum), which had their own ‘second wave’ in the late 20th century borne largely upon the convergence of conceptualism, especially in its multi-media manifestations, and feminism (as both feminist second wave phenomenon and the spectrum of political and cultural changes that ensued in its wake). This is more or less routine business in the art world since Renaissance portraiture. Although a great deal of attention has been given in recent years to LGBTQ and gender issues expressed in such art, I think the real instigator is much more geophysical and existential than cultural or social-psychological. Whether or not we acknowledge it, we all recognize how close to extinction we actually are. Where we once might have awakened to the question, “Who am I?” we’re now as inclined to pare it down to, “Am I?” – no ‘who’ or ‘what’ required. (This extends to a level of ontological reexamination evident in some recent art, the human relation/intervention with the ‘object’ or its perception.) It follows that we (a) have no time to waste over anyone’s hang-ups regarding any aspect of our (gender-or-whatever non-conforming) identity, and that (b) we will project ourselves into that environment by whatever means (including technological) practicable, reserving and privileging our most cherished fantasies of that ‘I’ to express as we will.

Fashion has more than a little to do with this – not simply to the extent it may be exploited as a prop or an aspect of representation, or even a fully integrated collaborative component, as art-fashion collaborations have proliferated over the last two or three years – but because fashion has always been an integral aspect of the way we imagine, create and respond to art. But still more importantly, and especially in an urban culture – before we approach the level of art – it’s integral to the way we construct personal identity.

![Helen Rae, "April 27 2016" [Simone Rocha] colored pencil/graphite on paper, 24x18](https://artillerymag.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/HelenRae-Prada-226x300.jpg)

Helen Rae, “April 27 2016” [Simone Rocha] colored pencil/graphite on paper, 24×18

We’re all born frantically slashing at the atmosphere and environment before the structural supports (or their absence) even register. In our helplessness, it’s enough at first to simply be nourished and supported, but most of us immediately get that there’s something more. Right away we get that there are expectations ‘out there’ (however vague that concept might be) – including our own; and judgments – even if they’re only coming from the face in front of us, immediately entailing the question: who are you? This is a participation game where there’s no right answer and no winning. And it only gets worse – nature, however civilized, is blood-red at tooth and nail. Going out into the world, we need, as Daphne Guinness put it memorably, armour. But ‘out there’ we get to push back a bit; we can take a stab at who we think we might or might want to be – which is usually where matters of style and fashion come into play. The architecture is already there, the ground rules imposed. Fashion gives us a set of tools to tweak those rules, to morph the surround, to activate and transform the architecture in place. It’s about attitude of course, but also a much broader, more articulated construct of signs, signals and symbols, conveying an idea of self, of personal agency, within a society. It’s a continuum of juxtapositions, some of them more radical, more transformational than others. Fashion is about where the pose meets the point of juxtaposition.

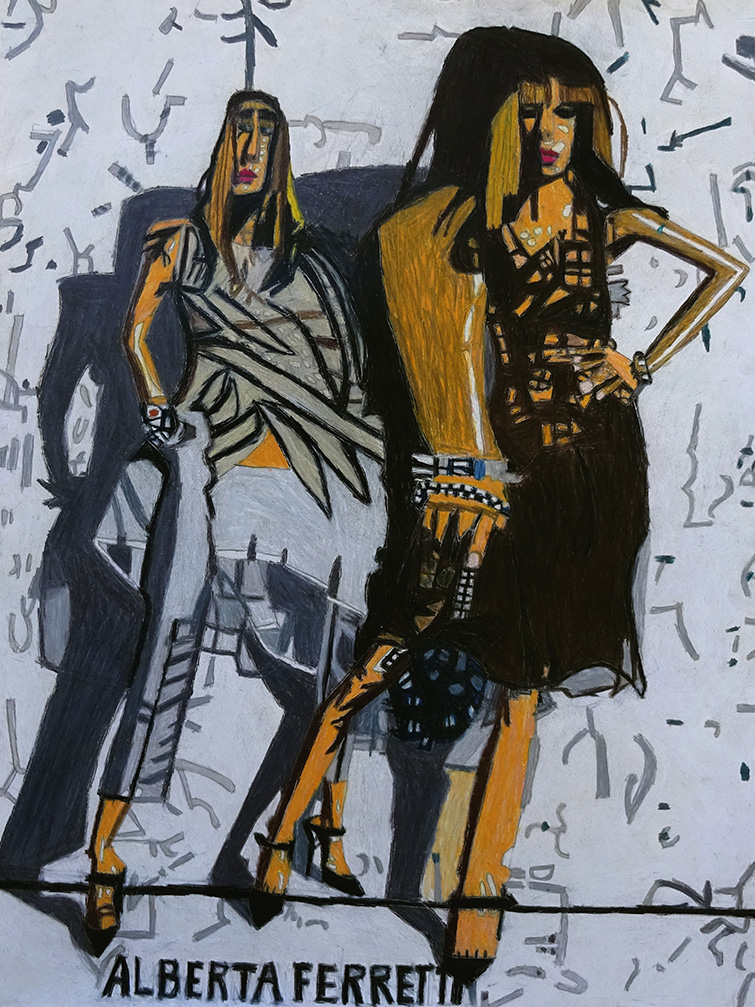

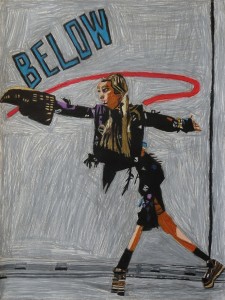

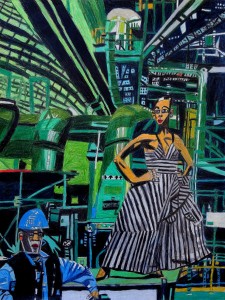

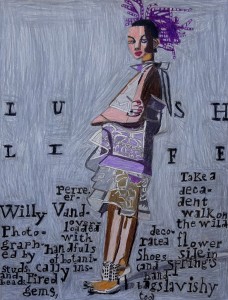

Helen Rae engages the world of high fashion the way most of us do, by way of fashion magazines and fashion photography, which are a huge part of the fantasy of fashion (also, in commercial terms, an engine of consumer interest and desire). Great fashion photography is also simply great photography; and at its best (even in advertising) expresses something not merely essential to the designer’s (and stylist’s) vision, but true to the cultural moment, the Zeitgeist. Helen Rae appreciates that truth and fantasy – and even gives credit to designers/brands and photographers – but her art is more about a personal and intimate communion with that fantasy. While remaining remarkably faithful the original photographer’s or stylist’s look or mise-en-scène, colors and patterns are tweaked just so, accessories are given new emphasis or exaggerated in proportions, lighting gives way to overall backdrop, pattern and silhouettes. Patterns and embellishments are themselves reworked, the settings (with a few very ironic exceptions) reduced to all-over pencilled or graphic backdrop. One interesting sidelight is the insight Rae brings to the design process itself. As she tweaks or distorts a cut or pattern, she reveals new variations, new possibilities. (As anyone who lives in L.A. knows, unless you’re part of that half that only wears sweats or T-shirts and cargo shorts, you never stop zhuzhing.)

But most important is what she does with the pose – or more precisely the pose as the keystone accessory, the pose as it intersects with the surrounding space – and the face. Elongated limbs meld into accessories to resemble something prosthetic or almost bionic. Exaggerated details and shadows suggest an entirely hidden dimension to the tableaux. The face becomes the mask; multiple, morphing masks; at the edge of real distortion, almost Cubist, and in a few instances unquestionably Surrealist, a lion, a samourai, an Apache, a Shibuya girl; her mask.

If you routinely look at fashion, you’ll probably recognize some of the designs. (You may even recognize the recent editorial spread Rae more or less directly quotes from.) Overall, the original clothes are pretty alluring; but you may leave The Good Luck Gallery preferring Helen Rae’s version to, say, the original Simone Rocha or Oscar de la Renta. Helen Rae’s reworked Alberta Ferretti and Fendi ads are so strong that the two design houses would be well-advised to swap out the original ads with Helen Rae’s transformations (especially for their art magazine advertising). Except for a blue anemone garland, Rae’s versions of the Julien d’Ys headdresses here look slightly tech or digitized (as if Klimt were doing a Lego edition), but we might also assume they’d be less perishable. I must say, too, I got a bit of a giggle at Rae’s drawing of L.A.’s conceptual art godfather trying to find his fashion comfort zone with something besides Hedi Slimane’s Saint Laurent Paris. (Looked like Proenza Schouler to me.)

What Rae aspires to with these paintings is a moment of transfiguration that is the answer to the power of ideal physical form, the power of pure beauty. Rae is not necessarily transporting us to that Olympian dimension. Instead she’s bringing it all back home to that place where we can reinvent beauty – or the customized mask that represents our conceptual reconfiguration of it – on our own terms. Like any other beauty, it is fragile and vulnerable, but no less challenging and no less powerful.