Gerardo Monterrubio marks his ceramic sculptures with his memories and experiences as an Oaxacan immigrant. Free-flowing drawings upon his pottery relate engrossing autobiographical narratives interlaced with cultural commentary. His work recalls a vast historic spectrum of pictorial clay: cave paintings, Greek amphoras, Mesoamerican vessels and Grayson Perry vases.

Monterrubio’s early recollections sound as though they could have taken place centuries ago. His devout family made yearly pilgrimages to the shrine of the Virgin of Juquila. These multi-day hikes on dusty footpaths made him keenly aware of how Pre-Columbian traditions had become embedded in Catholic ritual. Some towns were so remote and unspoiled by the conquest that Spanish wasn’t even spoken. His own native grandmother expressed herself in a dialect of Zapotec and Spanish.

La Malintzin, 2009 (detail), Porcelain, wood, holy water, blood, photo Anna Marie Impullitti

La Malintzin (2009) is titled after the symbolic matriarch of all Mexicans, Hernán Cortés’ Nahua mistress who ostensibly bore the first mestizos. It depicts Christ crucified on driftwood, his blood-spattered ceramic body inked with grinning skull-like indigenous symbols. This grotesque fetishistic piece poignantly aligns European and Mesoamerican religions’ sacrificial gore. In addition to the persistence of cultural tradition, Monterrubio’s tattooed surfaces suggest how early decisions and inculcated values affect individuals throughout their lives.

Monterrubio emigrated to LA in 1989 at the age of 10 and became a graffiti artist in his teens. Had he stayed in Mexico, he would probably have become a doctor or lawyer, he revealed. However, his bull rider grandfather inspired him to strive for a more autonomous existence. His interest in drawing expanded to three dimensions when he became enamored with clay while taking a class at Los Angeles City College.

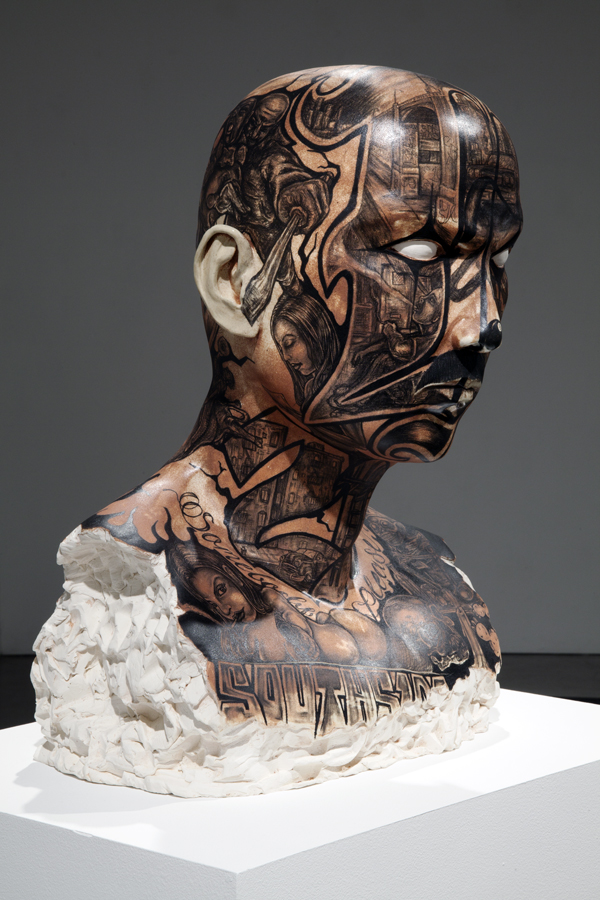

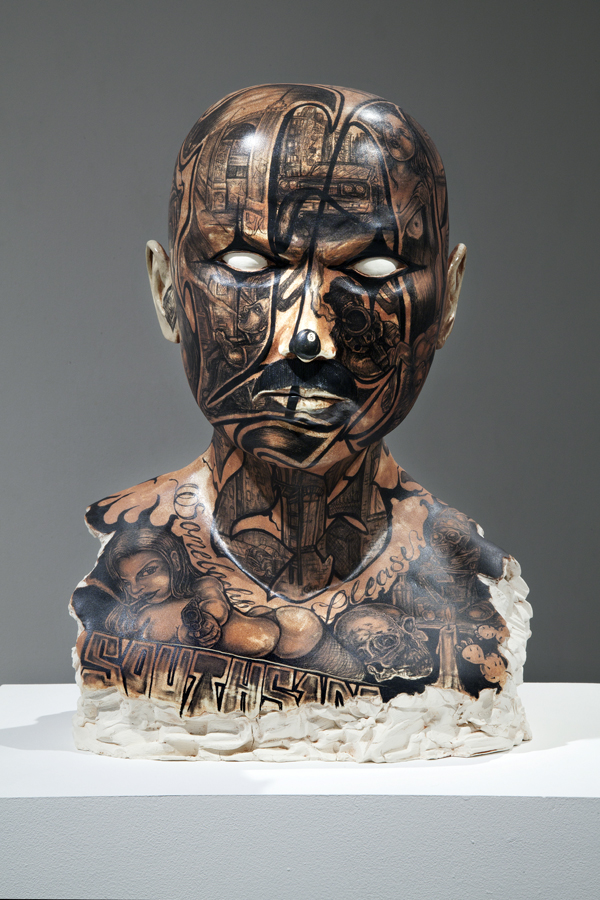

Scooby WS White Fence LS, 2013, Porcelain, photo Jeff St. Andrews

Desiring to incorporate more personality than functional forms and traditional glazes would allow, he began drawing with an underglaze pencil on porcelain sculptures. These images delineated ancient Oaxacan myths in a contemporary style inspired by prison drawings, tattoos and the underground Chicano magazine Teen Angels.

Monterrubio’s passion for drawing on ceramics led him to earn a BFA from CSULB in 2009 and an MFA from UCLA in 2013. As he progressed toward these degrees, social commentary infiltrated his work, which became darker and less cartoonish as he explored sordid themes relating to tragedies he had witnessed in the U.S. and Mexico. Eduardo Arellano Felix (2009) depicts the eponymous baldpate cartel leader as tattooed with horrors of addiction and incarceration. Closer to home, Scooby WS White Fence LS (2013) is a bust of a friend of Monterrubio’s who is serving 50 years to life in Pelican Bay, his hardened mien inked with sobering scenes expressing things he “can’t say in words but are a second skin, almost like a cry for help,” the artist said during a recent lecture.

Eduardo Arellano Felix, Porcelain, 18x13x10 in. 2009, photo Gerardo Monterrubio

La Normandy and 8th (2013) immortalizes fresh blood seen outside a Central LA liquor store, a grisly childhood recollection that he says discouraged him from criminality. Monterrubio likens local gang violence to incidents in Oaxaca, observing in both countries ruthless patriarchal subcultures that he deems “toxic masculinity.” His uncle, he says, was beaten, left for dead and permanently paralyzed for being gay. Oaxacan boys were required to help sacrifice goats; if they showed emotion for the slaughtered animal, they were given shots of mescal. Vignettes from such experiences are interwoven with American and international bugbears in colorful and painterly recent works such as the sanguinely glazed Pinches Borrachos (2017). Aligning with Monterrubio’s affecting illustrative content, the surfaces of these relatively traditional forms are mutilated and scabrous in reference to ingrained human brutality that transcends time, place and ethnicity, an ongoing concern of the artist.