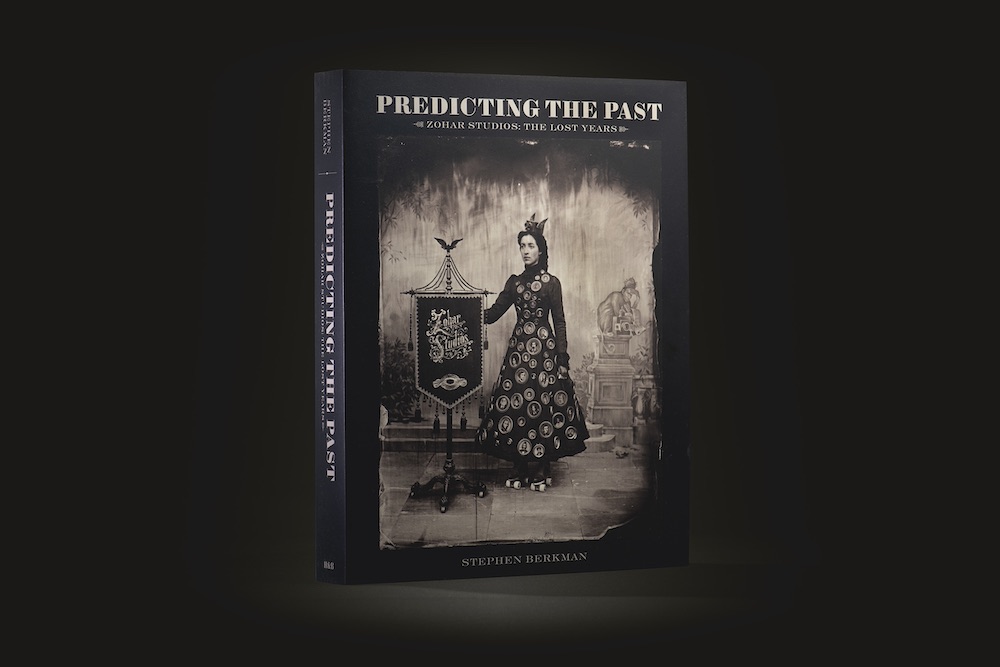

As a maker of books, I met artist, photographer, director and historian Stephen Berkman in the “before time,” when fonts and spelling and public exhibitions of artwork seemed of import. Berkman, you see, was coordinating “Predicting the Past, Zohar Studios: The Lost Years,” a show of mostly large-format, glass-plate photography for The Contemporary Jewish Museum, and also producing an accompanying eponymous book—or was it the other way around? And while the physical show was in colloidal suspension, represented for months by a virtual doppelganger accessible through the world-wide web, the book, printed in Italy only days ahead of the virus arriving there, miraculously made it to our shores.

I recently talked with Berkman in his Pasadena studio. The inescapable smoke from a nearby forest fire contributed atmosphere as we spoke—voices muffled by our leather-beaked plague masks—about his achievement.

Bill Smith: The first thing one notices about your book is the size. Its heft alone has warped the engineered sawdust planks of my IKEA Billy bookshelf into a permanent smile. The spine, a monolith easily several inches taller than any of its bound neighbors, mocks me. I’m a monkey wielding a bone and I am vexed at its dark presence.

Stephen Berkman: I can only say that after working on this book for 20 years, one expects to see a weighty tome, and not something the size of a pamphlet. I wanted to create an encyclopedia of the 19th century that was both expansive and expressive. The format of the book grew out of this desire, with the foundation being the photographs, complemented by the annotations and the ephemera, which take the reader on a discursive journey beyond the surface of the image and into the world that the photographs emanate from. This book revisits 19th-century history through the prism of photography. I hope it’s engaging and thought-provoking, and will perhaps provide enough entertainment to occupy a fortnight… or two.

Predicting the Past book.

The era of your focus clearly relates to the dawn of photography, but are there other aspects of that time which interest you?

The book is panoramic by design—it’s a compendium of historical antecedents, taking into account myriad aspects of the 19th century, chronicling both the quotidian and sweeping cultural influences. The 19th century was a beguiling and vibrant era but regrettably, it’s often painted in broad strokes. I was more interested in uncovering the details and nuances of the time in order to offer a variegated account.

One section of the book chronicles the various whimsical and ingenious cameras obscura invented by your subject, Shimmel Zohar. Do you recall your own first camera?

My first camera as a child was a box camera that I made out of cardboard. Instead of a lens, it had a pinhole that required long exposures on photosensitive paper. I was disappointed that the images looked like they were from another time, instead of duplicating what I could see with my eyes. At that stage, I wanted to take photographs that looked contemporary. The pinhole camera seemed too rudimentary to me—what I really wanted was a modern 35mm single-lens reflex camera. I graduated to one sometime later and stayed with it for many years. But I finally became disillusioned because everything I photographed appeared too contemporary. After abandoning that camera, I predictably came full circle. For the past quarter-century, I’ve been photographing once again with a box camera—this time made of wood and with a Petzval lens. It’s slightly sturdier than my first cardboard camera, but it’s still photography in its most elemental form.

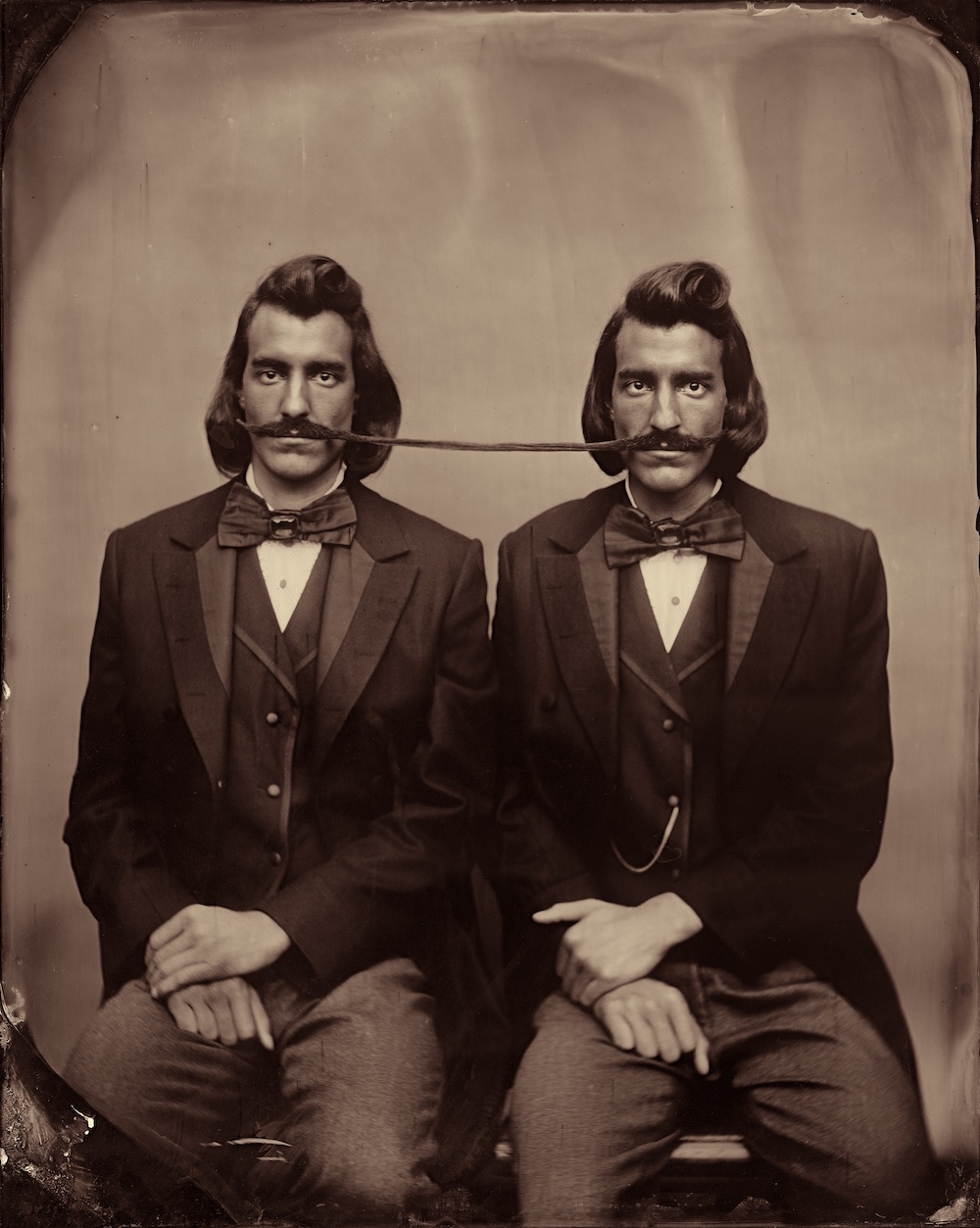

Stephen Berkman, Conjoined Twins, undated. Albumen print, 11x 14 in.

In working on your book, it felt to me that the book became a new medium for you, with photography being focal, but supporting the greater piece. Is that how you saw it at any point?

From the outset, the book was my main focal point. Books can have a long lifespan. They are repositories of information and, like coiled springs, they release energy into the world when they are opened. They literally speak volumes, and they have an enduring ability to continue the conversation long after their authors have departed. I’m an avid collector of 19th-century photography books and, whenever I look at them, I feel like I’m still communicating with those authors. In the case of my photography book, I’ve always envisioned it as a continuum of that conversation—building a bridge back to the 19th century.

“Predicting the Past, Zohar Studios: The Lost Years” has been extended through Feb. 28, 2021, The Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco, thecjm.org. The book recently made the Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards shortlist and is published by Hat & Beard Press.