The Stargazers show at the Frank M. Doyle Arts Pavilion in Costa Mesa, curated by gallery director Tyler Stallings to coincide with the opening of Orange Coast College’s state-of-the-art planetarium this month, interweaves scientific explorations of the cosmos with the mysticism of Jung’s collective unconscious. While created separately by five artists and three artist teams over the course of several years, the works’ interpretive liberties with astronomy data and history reflect stunningly common colors, placidity and mandala-like geometries evidencing Jung’s notion of synchronicity, or the uncanny coincidence of events pointing to a shared undercurrent of symbols and aspirations. Through meaningfully warped timeframes and spatial scales, the works guide us in turn through the cosmos—macrocosmically with the aid of astronomical tools, and microcosmically through our bodies as cavities of spiritual wonder—collectively inviting us to reconsider and resolve our position within it.

Husband and wife Russell Crotty and Laura Gruenther’s installation “Look Back in Time” (2016) slices the 14 billion-year history of the universe into epochal pages that fill the Doyle’s Project Gallery. While the installation grew out of Crotty’s residency with astronomy researchers at UC Santa Cruz in partnership with the Lick Observatory, the artists opted for pastel colors and childlike shapes and materials such as glitter and microbeads in lieu of literal depictions of supernovae, galaxies, the spectra and exoplanets, beckoning us to wonder our way through the bioresin-coated netting (referencing space plasma and amniotic fluid) like children in an enchanting fairy tale of our origins. The subtle spiraling of sculptural orbs between the still scrims invokes a meditative trance; through unrushed footsteps we retrace eons of elapsed time from our modern universe at the entrance to the Big Bang at the back wall, and through the spacious silence of our bodies we extrapolate the artists’ primal blobs, swirls and bars into the explosive and exquisite drama driving the universe’s generative expansion.

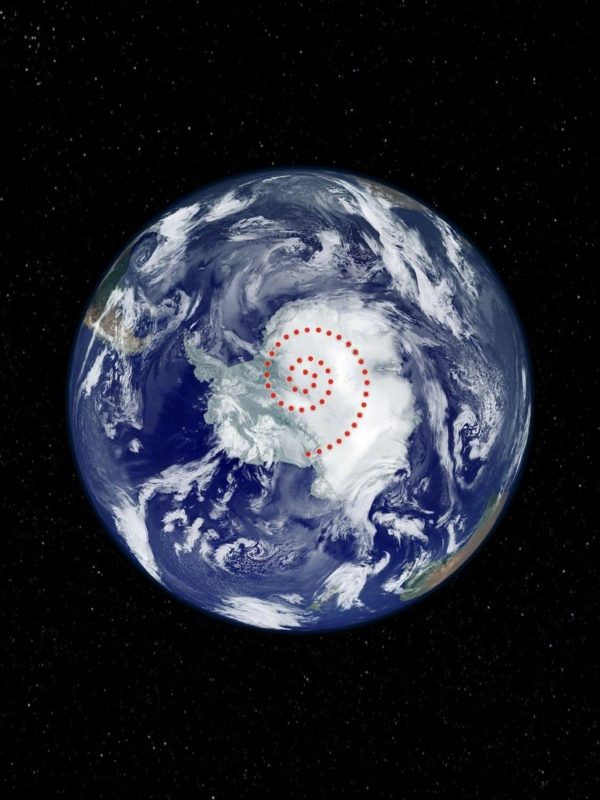

Lita Albuquerque, South Pole Activation (2014)

Our meditative expedition continues in the Main Gallery, where graphic opposing spirals in Lita Albuquerque’s “South Pole Activation” (2014) and “North Pole Activation” (2014) signify the movement of the stars across each pole as the earth rotates on its axis and around the sun. Evincing the basic geometry of a mandala—a symbol, across myriad spiritual traditions, of the universe and of the wholeness or center of the self—these spirals further align us with the earth and ourselves by centering our gaze and awareness on the planet. Commemorating large spiral chains trekked in the snow by Albuquerque’s collaborators in the Arctic and Antarctica, human footsteps here again enacted the passage of celestial time. The first artist to do installation work at the poles, Albuquerque initially, in 2006, mapped the overhead positions of the 99 brightest stars during the summer solstice on the Antarctic snow with 99 ultramarine blue fiberglass spheres. Historically a precious hue entailing origins “beyond the sea” and the power to induce spiritual awakening, ultramarine blue alludes to the stars’ mystical dance beyond earthly horizons.

Carol Saindon, Outside of Inside (2019)

Another pair of opposing spirals referencing the sea and its celestially driven tides erupts in Carol Saindon’s “Outside of Inside” (2019), where stars reflected in shattered blue glass gravitationally swirl in a binary star system on a collision course. As with Albuquerque’s prints, we are transported beyond the earth to reencounter the universe and our position relative to it, here through hypnotic binoculars or reflection pools. What does it mean, the work seems to ask, for the infinity at the center of each star to double as a result of their collision, and for our earthly physical labor—represented by poured and ploughed glass—to intersect these cosmic dramas? We are thus invited to contemplate the paradox of creative expansion resulting from cosmic detonations (like the Big Bang), and to question the meaning of our activities and agency within epic cosmic dramas. Saindon’s charcoal drawings of Hubble images on the adjacent wall echo her meditative practice of observing and manually harnessing the cosmos, alluding to gestures of transcribing or coauthoring pages of its story.

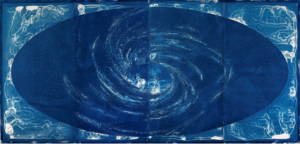

Lia Halloran, Triangulum, after Adelaide Ames (2017)

Female gestures of manually harnessing and coauthoring oceanic spirals of the cosmos are echoed in Lia Halloran’s towering “The Great Comet, after Annie Jump Cannon” (2016) and “Triangulum, after Adelaide Ames” (2017), two cyanotypes referencing telescope images captured on glass plates by men, but often examined and catalogued by women known as the Harvard Computers in the 19th and 20th centuries. Part of her “Your Body is a Space That Sees” series, these elliptical mandalas center our bodies in female vistas borne out of female labor, employing the cyanotype production process to mirror the women’s physical work under the sun, and to magnify the pioneering gazes of women such as Jump Cannon and Ames who helped identify and develop classification systems for celestial objects. While employed by men for often substandard wages, some Harvard Computers were lauded and published in an era where women were widely dismissed, highlighting a glimmer of idealism in the spirit of cosmic exploration toward progress beyond the acquisition of knowledge.

George Legrady, Stardust VI 3D (Gold) (2008-2018) and Stardust III 3D (Blue) (2008-2018)

Further exploring our authorship of the universe’s story, George Legrady’s “Stardust VI 3D (Gold)” (2008-2018) and “Stardust III 3D (Blue)” (2008-2018) present data visualizations of thousands of sightings of comets, galaxies, stars and other celestial phenomena made by scientists over several years through Caltech’s NASA Spitzer Space Telescope. Mirroring the scientists’ subjective-objectivity, the images situate us at the visual center of their frames and thus at the center of the universe, out of which celestial orbs emanate as observations. Like the show’s other artists, Legrady colored and energized his orbs through intuitively creative rather than directly representational methods, radically collapsing the elapsed time and spatial scales associated with the data into a pair of lenticular prints effecting subtle holographic pulsations. Once again evoking the radial balance of mandalas, these silent fireworks evoke celebratory contemplation, stirring at once delight in our technological ability to acquaint ourselves with the cosmos, and concern over the validity and responsibility of situating ourselves at its center.

Left to right: Clayton Spada and Victor Raphael, Neutral Current (2014/2018), Entropy (2017/2019), Expulsion (2012/2019), Eclipse (2015/2018)

Clayton Spada and Victor Raphael’s pigment ink and gold leaf panels from their ongoing multiyear “From Zero to Infinity” project propose an alternative mythology of humans’ position in the universe. Beginning with the Big Bang in “Neutral Current” (2014/2018), the artists move through “Entropy” (2017/2019) to human’s arrival on the scene in “Expulsion” (2012/2019), reimagining our Biblical expulsion from the Garden of Eden as the Cosmos parentally pushing us to become creative explorers. “Eclipse” (2015/2018) admonishes us, however, not to idealize the Cosmos as unconditionally supportive, reminding us of the abandonment our ancestors felt when they could not explain the sun’s disappearance during an eclipse. Presenting the history of everything in four allegorical tapestries, the pieces invoke the mysticism of a quaternity, inviting us to consider what a wholly resolved human understanding of the universe would entail, if one could be apprehended at all.

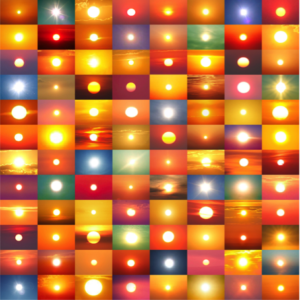

Penelope Umbrico, 31,838,202 Suns from Sunsets from Flickr (Partial) 10/15/16 (2016)

The deification of the cosmos, particularly the sun, is central to Penelope Umbrico’s “31,838,202 Suns from Sunsets from Flickr (Partial) 10/15/16” (2016) featuring appropriated photographs of sunsets taken across the globe. As sunsets are among the most photographed images online, questions of our authorship and ownership of the universe resurface in the context of sun worship. On one hand, Umbrico’s serial collection celebrates to a visually pulsating beat our distinctly contemporary and communal adoration and awe of the sun. On the other, the surfeit of disposable digital copies ironically flattens our once sacred relationship with the sun to easy ownership of its image, devoid of commitments to physical labor in memorializing its positions and movement. Such easy ownership leads us to view the sun as more of a decorative or aesthetic object than one calling us to revere its life-giving power. This “dark side” of the democratization of cosmic photography is alluded to in “31,838,202 Suns from Sunsets from Flickr (Partial) 10/15/16 Negative” (2016) featuring an inversion of the set.

United Catalysts, Skywheel Tower Model (2019); Wall and detail: Goddard Mandalas Series (2009 – present)

Kim Garrison and Steve Radosevich of the artist duo United Catalysts present a final invitation to recontemplate ownership of the skies through the Skywheel Project, a growing catalog of steps that began in 2008 toward the launch of an earth-orbiting satellite housing positive intentions for the planet (mirroring a Tibetan prayer wheel). Their Skywheel Tower Model (2019) figuratively channels the power of our collective goodwill from the ground to the model satellite which, lifting off through the gallery’s skylight, would circulate that energy around the globe. In depicting this energy transfer via a modern transmission tower, the artists imagine our invented technologies integrating our communal consciousness with the cosmos in nurturing and reverential ways, rather than through privatization or militarization. Initially inspired to begin this project by Robert H. Goddard’s pioneering rocket development experiments, the artists’ homages to his mandala-like circular technical drawings appear in a quaternity as part of their Goddard Mandalas Series (2009 – present). Visitors may contribute positive intentions to be placed in the real future satellite at the gallery or through the artists’ website after the show.

Goddard and the Harvard Computers revolutionized space exploration in the same era Jung and modern artists revolutionized exploration of the psyche in the 19th and 20th centuries. Through meditative shapes, scales and hues the show invites us to iteratively observe in spiraling turns these stories of the cosmos and our authorship of them, as well as the nature of our ownership of the universe (be it commodifying or caretaking) and of our consciousness as a reflection of it. Through the centering, expansive silence of our bodies resulting from this extended meditation, we reencounter a simple childlike wonder largely illegible to commercialism, war and other competitive agendas but more rudimentarily human. In this state of alignment with the mystery of the universe, we can reimagine sacred possibilities for human creativity, ambition and labor to articulate with the universe’s ongoing expansion.

Stargazers: Intersections of Contemporary Art & Astronomy, Feb. 7 – Apr. 6, 2019, at Frank M. Doyle Arts Pavilion, Orange Coast College, Costa Mesa, CA http://