As a practitioner of curanderismo, an ancient Meso-American system of folk medicine, Mexican-born, Chicago-based Luis Sahagun regularly performs limpias, traditional cleansing or “soul-retrieving” rituals. As an artist, he has applied this practice to the creation of portraits of people, living or dead, who are the chosen beneficiaries of his healing efforts. For a recent exhibition at Charlie James Gallery, he turned the LA gallery into a chapel of sorts, with its shrines consisting of healing portraits of family members, including himself.

In his role as a curandero, Sahagun seeks advice from the Mexican Medicine Wheel, which is divided into four sections (north, south, east and west) that list various “medicines” such as the natural elements, certain animals, the four seasons and certain stages of human life. According to the artist, “We call it walking with our medicine. This system holds a deep connection to the invisible and intangible higher source, which can be defined as a belief system with faith and energy connection.” By “medicine,” of course, Sahagun is not referring to a pill. He explains, “In my limpias I go into the spirit realm to seek knowledge or help on what is best needed for the sitter to use as medicine for their journey. Medicine is not just a chemical makeup that takes away a headache, but rather medicine as in what your spirit and soul need to be nourished.”

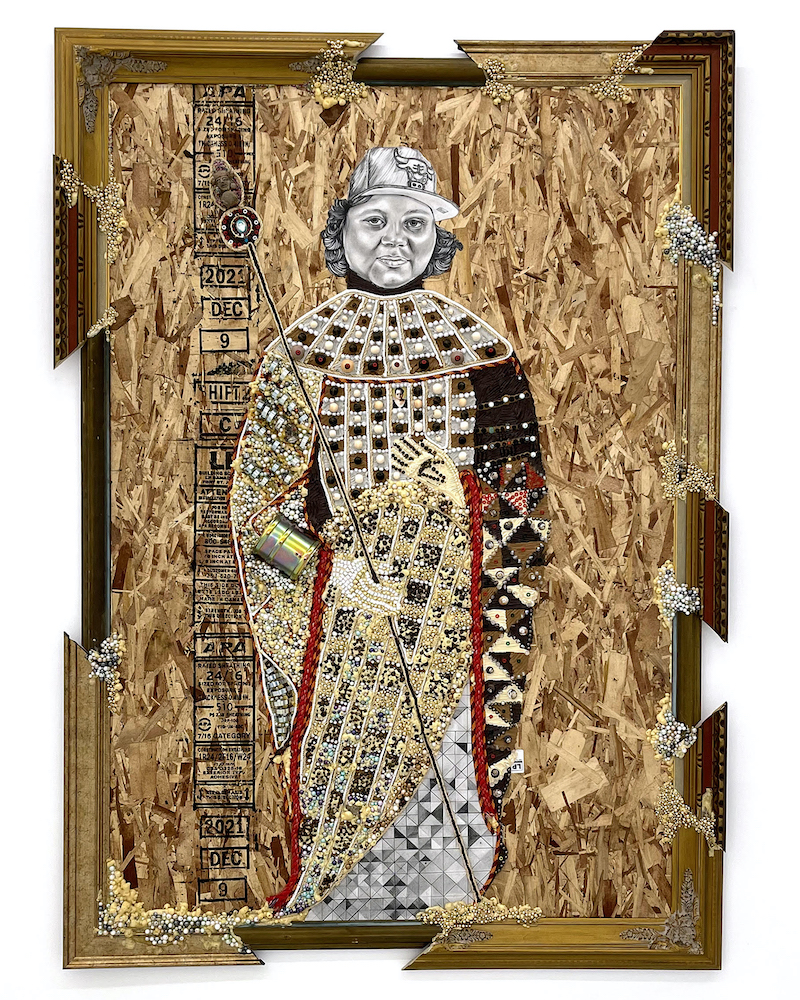

Luis Sahagun, Maria Bonita, Maria del Alma, 2022. Courtesy of Latchkey Gallery.

To begin a portrait of a living person, Sahagun functions as a spiritual consultant. In preparation for Limpia no. 1 (Maria “Mariquita” Rodriquez Sahagun), a portrait of one of his sisters, he asked his subject for permission to perform a cleansing rite and, once she agreed, the two exchanged phone calls and text messages to assess her emotional situation, how she needed to be healed, and what burdens she wanted to release. He then advised her to incorporate some specific rituals into her daily routine and informed her as to when he would be working on the portrait, so that they could share spiritually in the ritual’s energy. Next, he embarked on what he considers to be a shamanic journey, using the medicine wheel “to procure the cleansings, healings and/or purifications” that are needed as he taps into the spirit world by connecting with his Nagual, or spirit guide. Sahagun then worked on the portrait over a number of sessions while performing limpias, drawing facial features in charcoal and fashioning clothing and other features from miniature sculptures he makes to “communicate” a recommended medicine. He also adds to the mix custom-made resin beads that are “charged” with plant medicine, crystals, chants and photographic images deemed important to the subject.

From a therapeutic perspective, Sahagun considers a finished portrait to be “an individualized treatment aimed [at facilitating] healing of the heart and soul via herbs, energy work, counseling, rituals and spiritual cleanings.” Yet, in examples such as Limpia no. 3 (Jose Luis “Don Chepe” Sahagun Sotelo), it is also a symbolic representation of the historical and cultural survival of the immigrant laborer. The subject—the artist’s father—left Guadalajara for Chicago in the 1970s due to the gang violence he encountered while working as a bus driver. Undocumented for many years, he labored in fields and steel factories before landing employment as a truck driver. In this and other portraits, Sahagun refers to the laborer by building supports for the paintings from construction materials such as drywall, concrete, silicone and lumber. In the rendering of his father, he portrays his subject as a strong, dignified survivor by appropriating the style of 17th-century royal Spanish portraiture, and crowning him in a kingly manner with a fragment of an ornate vintage frame positioned directly above his head.

Luis Sahagun, Soul Retrieval no.3 (Luis Alvaro “Alvarito” Sahagún Nuño), 2022. Courtesy of Charlie James Gallery, Los Angeles Photo – @ofphotostudio.

When communing with the spirits of deceased figures, Sahagun relies on carefully selected old photographs, such as one of his grandmother in her 20s as the basis for her portrait. Similarly, he turns to photos of himself at several ages for his self-portraits. For one example, he sought to heal the wounds of racism he experienced while a college student at a predominately white institution, and thus focused on a photo of himself from that period while consulting with his spirit guide.

Whether or not one believes in the efficacy or validity of the healing powers intended by Sahagun’s portraits, we can all certainly appreciate their symbolic and aesthetic reverence for the enduring heritages of indigenous peoples.