The desert is a surprising place, and we see it anew when artists are drawn there by site-specific projects such as “Spectacular Subdivision,” which took place recently in Wonder Valley over the weekend of April 4 through 6. About 35 artists made work for two sites, one at the IronAge Road tract of desert owned by artist Andrea Zittel, the other in and around a house a few miles away. Curated by Jay Lizo, “Spectacular Subdivision” was a collaboration between Zittel’s High Desert Test Sites (HDTS) and Monte Vista Projects (an artist-run organization from Highland Park, CA). Much of the fun was discovering artwork as one rambled about the 40-acre Iron Age site— yep, there was a map, but a very rudimentary one.

The exhibition was prompted by reflections “on housing and real estate in the aftermath of the 2008 housing market crisis,” says Lizo, and considerations of artists and space. We got that theme right away at roadside, where a billboard by Oliver Hess announced “Iron Age Road Estates,” replete with illustration of a futuristic residential development. (Of course, never to be realized.) Behind that, dotting scrubby desert, were installations by 20 other artists—most of which could not be seen until you walked right up to, or happened upon, them. They varied from full-scale installations such as Lara Banks’ “The Dead Garden,” Sam Scharf’s “Home Sweat Home,” Nuttaphol Ma’s earth-excavation project “The China Outpost Overlooking HDTS,” Lizo’s cardboard playhouse “Firework Catan House” to individual, portable objects such as Ken Ehrlich’s “The Desk” which was, yes, the sculpture of a desk (with nonfunctional drawers) posed against the backdrop of a mountain chain.

Banks’ “The Dead Garden” was one of the most fully and beautifully realized. A small homestead was outlined by wooden boards, with the “front” graced by several small “plots” of very dead household plants, all dried stem and desiccated branches. Eight more were in a larger plot, arranged in an above-the-ground planter box. Each dearly departed plant was backed by a tombstone with identifying words stenciled in white, such as “Green Rosemary” or “Bank Strawberry.” Banks collected these from various people, and in her artist statement she says, “I want this to have a participatory kind of culpability thing.” To me the installation did not convey so much guilt as homage, a way of honoring those plants we try to cultivate in our parched landscape—as well as a nod to all those people who came out to this region to “cultivate” it. There’s also some humor in recognizing the human tendency to anthropomorphize everything.

Also arresting, and wonderfully site-appropriate, was Scharf’s “Home Sweat Home.” Protruding in the sandy expanse was a corner of the roof line of a house and a bit further away, where the yard of the phantom house would have been, a bit of picket fence with the house number on it. You could imagine the rest of the house being buried underneath the sand—and standing in the aftermath of that tornado Dorothy got swept away in.

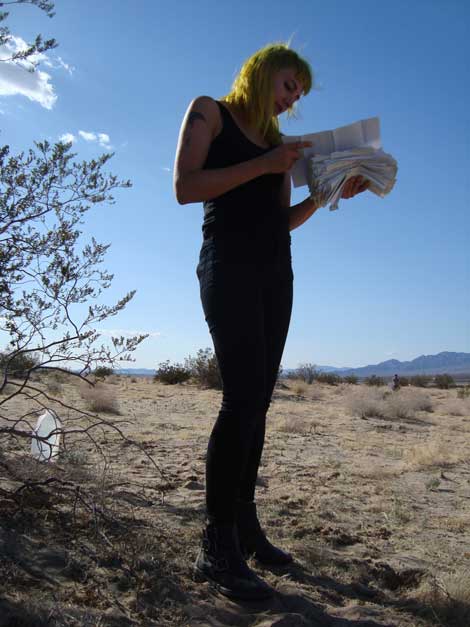

Anastasia Hill “SHU”

Out in the desert, Hill read letters from a man who wrote to her family from prison for 8 years

One of the most poignant works was one of the most simple—for “SHU,” Anastasia Hill stood by a tall shrub with a handful of letters in envelopes. She would pull out a letter and begin reading it aloud—letters from a man whom her family had helped over a time, including financially, and who had been in prison for much of an eight-year period covered by the letters. There was the sharp irony of her standing out in the vast open expanse, reading letters from a man restrictively confined. Still, one senses his instinct for surviving setbacks, and his deep appreciation for the help he got from her family. From 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. on Saturday, Hill stood there reading loudly, even when no one was nearby to listen. “SHU” refers both to “Security Housing Unit” (that is, solitary confinement) and to an Egyptian deity who stands for both “emptiness” and “he who rises up.”

Photos by Scarlet Cheng