A wise person once said that if you want to catch people’s attention, speak softly. The curators of the 2019 Whitney Biennial, Rujeko Hockley and Jane Panetta, seem to have taken this advice to heart, assembling a show that doesn’t hit you over the head with gimmick or excess. Yet, it’s deeply engaged with social and political issues—as art in the age of Trump must be—and also deeply engaging. Overall, the art and the message are authentic, well-thought-out and executed, the “meh” moments are few, and the artists get the message across without losing sight of the “art” part.

Now in its 87th year, the Biennial is supposed to be a “snapshot” of art in America, presenting a broad cross-section of what artists across the country have been producing in the two-year span between biennials. Of course, given that two people are making the selection, it is bound to be somewhat subjective. This year, with 75 artists and collectives included, there is a strong emphasis on process and ephemerality, with performances and film given a major role. I was only able to catch one performance, Brendan Fernandes’ The Master and Form (2018/19), which features dancers interacting with minimalist sculptural forms. The dancers draw on the culture and discipline of ballet, bending and stretching supple flesh and sinew against unforgiving metal shapes to showcase the strength and vulnerability of the human body.

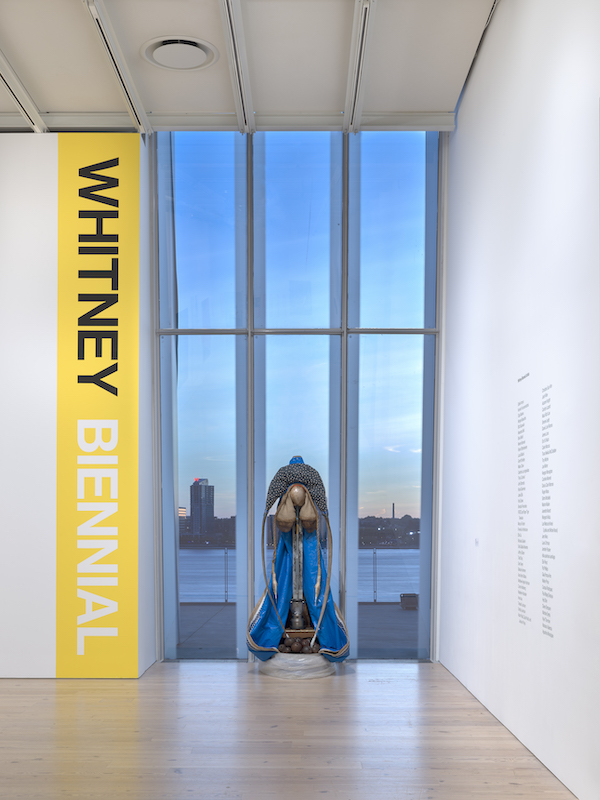

Installation view of the Whitney Biennial, 2019. Daniel Lind-Ramos, Maria-Maria, 2019. Photo by Ron Amstutz

Videos of note include Ellie Ga’s quietly enthralling Gyres (2019) and Forensic Architecture’s Triple Chaser (2019). Gyres explores how debris is borne across oceans, bringing with it the attendant human narratives. Through the objects, Ga recounts, in a dispassionate voice, stories of container spills, tsunamis and eventually her mother’s funeral. Along a border at the bottom of the video, her silhouetted hands transfer transparencies from one central light box to another. It is an elegant, poetic gesture that transforms recognizable images into shards of flotsam.

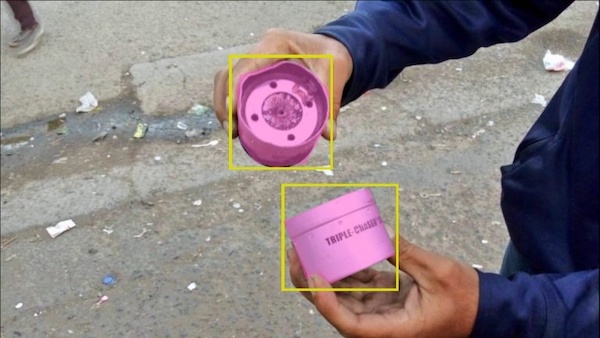

Forensic Architecture’s Triple Chaser, narrated by David Byrne, discusses the tear-gas grenade (of the same name) that’s been used against migrants at the U.S. border. It is manufactured by Safariland, a company whose CEO, Warren B. Kanders, is also Vice Chair of the Whitney Museum Board of Directors. The film veers from reportage to a seizure-inducing flash composed of images of a digital model of the triple chaser grenade against various psychedelic backgrounds. A visual roller-coaster ride, it’s actually a tool for improving the ability of computers to detect online images of the actual canisters. Identifying them will help track the global use of Safariland weapons.

Forensic Architecture, Triple Chaser (video still,) 2019

The simple sophistication of Nicholas Galanin’s White Noise, American Prayer Rug (2018) is exceptionally poignant. A Tlingit native from Alaska, Galanin confronts viewers’ preconceived notions of indigenous art. Here he uses the low-tech and soft medium of tapestry to represent a hard, mechanical TV screen. It’s a funny juxtaposition with the traditional medium ennobling the TV image. It also has a darker meaning as the snow that fills the screen, obliterating everything else, is a metaphor for White Supremacy.

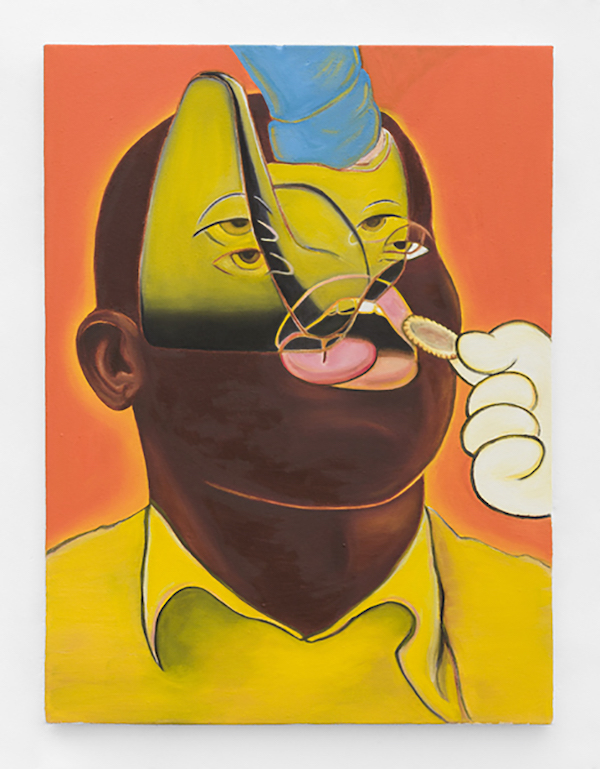

Arresting gesture and color-rich compositions mark the paintings and drawings in the show. Eddie Arroyo’s funky street scenes of Miami’s Little Haiti are imbued with a kind of jangly energy. Arroyo’s work is actually an indictment of the gentrification occurring in that city’s black and brown neighborhoods. There’s an appealing crudeness and also a sophistication to Pat Phillips’ work. He combines his experience as a graffiti artist with folk art to create work with immediacy and import. Jeanette Mundt’s series of gymnasts taken from New York Times images of the 2016 Olympic team have a splintered, almost twisting quality that calls to mind Francis Bacon. Composed of many small watercolor paintings made from actual footage of multiple NFL teams taking a knee, Kota Ezawa’s animation is both oddly bland and markedly pointed. Janiva Ellis paints big, using various inventive techniques to add texture and variety to her vast surface. Her enigmatic figures, one a cartoon character, add intrigue to the work. In Kyle Thurman’s “Suggested Occupation” series (2016–19), he’s made sketches of figures from online news photographs. The drawings, set against abstract blocks of color, feel light and insubstantial, yet simultaneously weighted.

Eddie Arroyo, 5825 NE 2nd Ave., Miami, FL 33137, 2017. Photo by Eddie Arroyo.

Christine Sun Kim’s Deaf Rage charcoal drawings address the many issues Kim faces as a deaf artist. Edgy, funny and seething with frustration, the work provides a provocative reality check for viewers with unimpaired aural faculties.

Gala Porras-Kim’s work straddles painting and sculpture. Using the La Mojarra Stela discovered in Mexico in 1986 as inspiration, Porras-Kim draws attention to the vibrancy of indigenous voices and culture that once existed but are now lost. The stela is incised with an Epi-Olmec inscription that is untranslatable. Porras-Kim’s work has a dignity and stateliness which mimics the antiquity of the stela while paying tribute to its enormous cultural value.

Josh Kline, installation view.

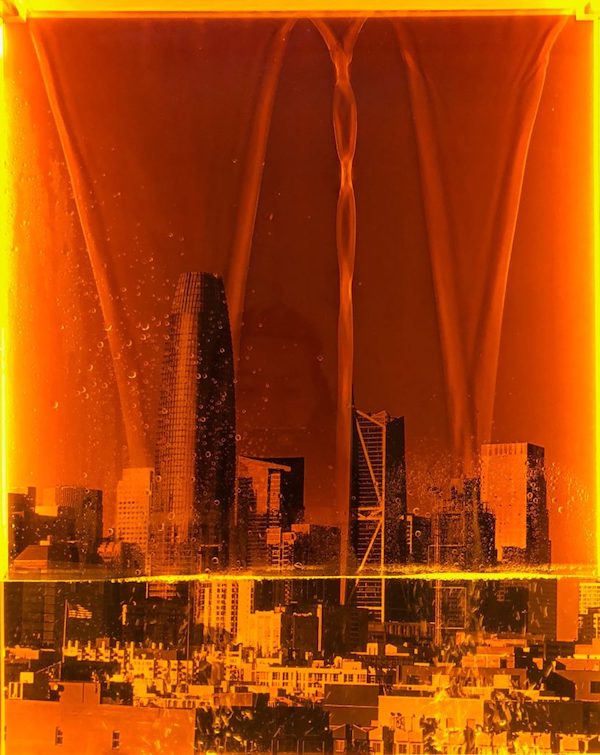

Other three-dimensional work of note includes Josh Kline’s series focusing on catastrophic climate change. Kline placed smartphone photos of American power (a statue of Ronald Reagan, the U.S. Capitol, a luxury home) within candy-colored LED-lit frames that continuously fill with water. Brian Belott’s mixed-media pieces certainly look interesting. They’re encased in ice, and displayed in three narrow glass freezers. It’s a clever idea, but given our potential imminent destruction by greenhouse gases isn’t this gratuitous use of energy a little passé? There’s something vaguely biological about Ragen Moss’ sculptures. Suspended from the ceiling, the sculptures first call to mind carcasses lined up in a butcher’s walk-in. But that impression fades upon examining their layers and juxtaposed patterns. You want to run your hand along the luscious mylar-like material and squeeze the puffed-up shapes. A FEMA tarp forms the iconic blue robe of the Virgin Mary in Daniel Lind-Ramos’ Maria-Maria, which also references the 2017 hurricane that devastated Puerto Rico. Lind-Ramos’ sculptural assemblages of found objects have a remarkable presence and elegance.

Daniel Lind-Ramos, Maria-Maria, 2019

Photography was well represented by Elle Pérez, Curran Hatleberg and Paul Mpagi Sepuya. Pérez’ photographs have a distinct grandeur. Pared down, the images are large in scale with an almost hushed elegance that Pérez uses to describe some of the harsher realities faced by those who seek to transform themselves—a glowing hand holding a vial of testosterone, a face that is both beatific and also bruised by facial feminization surgery, or the bloody word “Dyke” carved into someone’s thigh. Photographing the gritty landscape of the South is hardly new territory, but Hatleberg makes it fresh, picking subjects that pique our curiosity and packing his pictures with little visual bombshells: a girl in a destroyed house holding a snake, a prosthetic leg-wearing child among a group on a tumbledown porch, a gator lurking amongst the coreopsis. Sepuya emphasizes the relationship between artist, camera and image. His studio is often incorporated into his photographs. Sepuya challenges the concept of authorship by inviting friends to photograph alongside him. His collaboration with Ariel Goldberg is particularly striking; together they produced a small, unassuming photograph that is a knockout.

Installation view of the Whitney Biennial 2019. Elle Pérez photographs in center, Jeffrey Gibson sculptures hanging. Photo by Ron Amstutz.

Matthew Angelo Harrison’s sculptures are placed in the same gallery as Sepuya’s photographs. The angles and shapes of the sculptures echo those in the photographs, providing a rhythmic back-and-forth. From a distance Harrison’s work looks austerely contemporary. On closer inspection, you see that within the sleek rectangles of tinted resin are suspended African sculptures linking the contemporary with the traditional.

Throughout the exhibition, artwork is installed in ways that provoke dialogue between different artists. This worked really well with Carissa Rodriguez, Iman Issa and Milano Chow’s works. Rodriguez’ video The Maid focuses on objects, namely, Sherrie Levine’s “Newborn” sculptures. These are seen in the sumptuous interiors they occupy in New York and Los Angeles. The video almost veers into interior decoration porn, but with the drone footage skimming over snow-covered Central Park and the editing, Rodriguez wrests it back to the poetic. In Heritage Studies, Issa pairs contemporary sculptures with labels that describe antiquities to question value, preciousness and the influence of the old on the new. Chow uses graphite, photo transfer and collage to create her enigmatic architectural elevations and floor plans exploring ornamentation, taste and style.

Janiva Ellis, The Okiest Doke, 2017

Among the major themes of gender, race, equity and the body cited by the curators, I found a moment of personal resonance. I was deeply moved by Alexandra Bell’s No Humans Involved; After Sylvia Wynter, which revisits the Daily News coverage of the 1989 Central Park Five jogger rape case. I’m a white woman about the same age as the jogger. I lived in New York when the incident occurred. We actually went to the same college and I knew someone who was friends with her. So, it really hit home and I felt the fear back then. Looking at those headlines through today’s lens, I can’t help but be appalled at the frenzied vitriol and racism on display. It was this prevailing mindset (fanned by Donald Trump, who famously weighed in for the death penalty) that helped wrongly convict five innocent black men. Bell has held a mirror up to us to show what we are capable of doing when “fake news” infects and manipulates public opinion. Of course, nowadays it has gotten exponentially worse with the massive reach of social media and countless bad actors monkeying with the truth. Bell’s piece is a kind of memento mori but instead of death, it urges us to ponder our attitude towards race and to remain ever-vigilant against the propaganda confronting us daily.

Installation view of the Whitney Biennial 2019. Photo by Ron Amstutz.

As I walked around the Whitney, I kept feeling like something was missing. It finally dawned on me what it was: my anger and resentment—constant companions at so many art shows where pretense, affect and lack of soul prevail. I am thinking of past Whitney Biennials and Armory Shows I have attended and written about for this publication where shock and awe, at the expense of real substance, seemed the primary goal. I noticed too in myself a palpable lightness of being and realized that the exhibition had acted as a salve to my bruised soul. Despair was replaced by relief and gratitude seeing the thoughtful responses, the quiet, but persistent “wokeness” of artists across America as they grapple with the terrible times in which we live.

0 Comments