French conceptual artist Sophie Calle’s exhibition at the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature, “Beau doublé, Monsieur le marquis! Sophie Calle et son invitée Serena Carone” is Calle’s first exhibition in France since her retrospective at the Centre Pompidou in 2003, though she had a major retrospective at Fort Mason in San Francisco earlier this year.

The museum is housed in a 17th-century house built by Mansart in the Marais district in Paris, where the permanent collection consists of objects and symbols of hunting activity: taxidermied animals, weapons, paintings, and drawings—an eccentric kunstkamera akin to a more-specific Museum of Jurassic technology. It’s an apt space for Calle’s work, which explores the dichotomy between personal experience and objective reality. Calle frequently uses animals as symbols for her friends and relatives that readers of her art books will quickly recognize: a giraffe’s head named after her mother, a tiger to represent her father, a zebra, a crow, and more. For someone unfamiliar with the museum’s holdings, it might be difficult to distinguish between the permanent collection and Calle’s additions.

In an interview published several months before the exhibition, Calle said she was working with the museum of create an exhibition on “the hunting of women,” but this is not strikingly evident to me. It would seem more apt to think of Calle herself as a poetic hunter of men, stories, and experiences. She chases the memory of her father, to whom she dedicated the show, pores over Tinder profiles, and includes passages from her many books of pursuit: In Suite Venitienne, she follows a man she had met only once on a trip to Venice and documents the quest in black-and-white photographs and a leger with the intensity of a police report. In Address Book, she finds an address book on the street in Paris, and decides to contact those listed inside in order to try to produce an abstract portrait of its owner based on what his friends will confide about him.

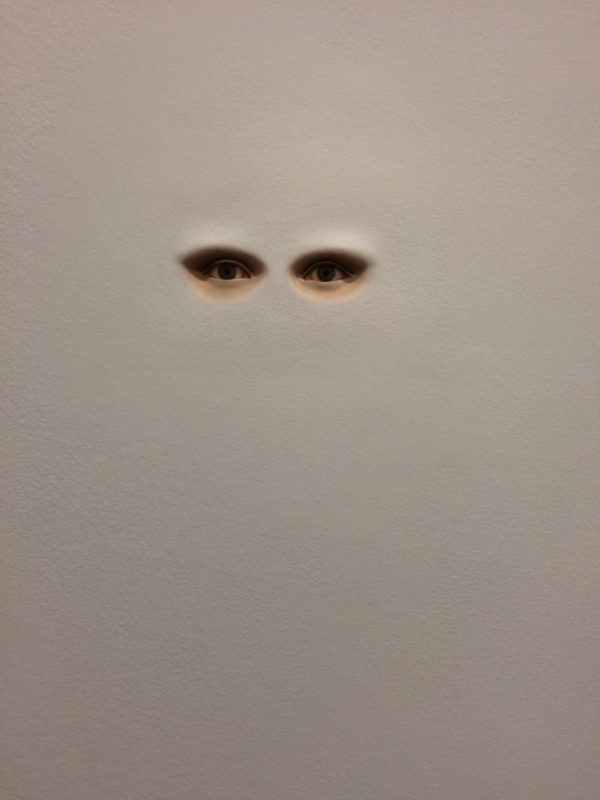

The show is similarly focused on what it means to be an observer and to be observed, and includes passages from several of Calle’s books as well as the artifacts pictured in them. This is common for Calle’s shows, often to critique. She said in an interview that the artist Daniel Buren, who acted as her curator for the 2007 Biennale, “began telling me that he loved my work but that many of my shows looked like open books on the wall… his criticism wasn’t about my writing — it was that for many works, I chose one format and repeated it many times.”

Perhaps this is a risk an artist takes in working with images and words, but to Calle, they are inseparable. Recalling the Bernadette Corporation’s collaborative poem A Billion in Change — which was displayed like a work of visual art in a gallery — critic Chris Kraus writes in her 2011 book, Where Art Belongs: “But as it turned out, the insertion of poetry, displayed like a work of visual art in a gallery space, was deeply disturbing to most. For years writers have played a circumscribed role in the visual art world. Our job is to write about art; to give it a language that translates into value.”

Calle seems not to have concerned herself with an audience’s potential resistance to text. “I don’t care about truth,”she said. “I care about art and style and writing and occupying the wall. For me, my writing style is very linked to the fact that it is a work of art on the wall. I had to find a way to write in concise, effective phrases that people standing or walking into a room could read.”

The exhibit is entirely in French, but for those familiar with Calle’s books it will provide delightful encounters of familiar passages and objects, along with some new works that seem to have been made specifically for the museum.

Beau doublé, Monsieur le marquis! Sophie Calle et son invitée Serena Carone is curated by Sonia Voss, and includes collaborations with ceramicist Serena Carone. Runs through February 11, 2018 at the Museum of Hunting and Nature in Paris.