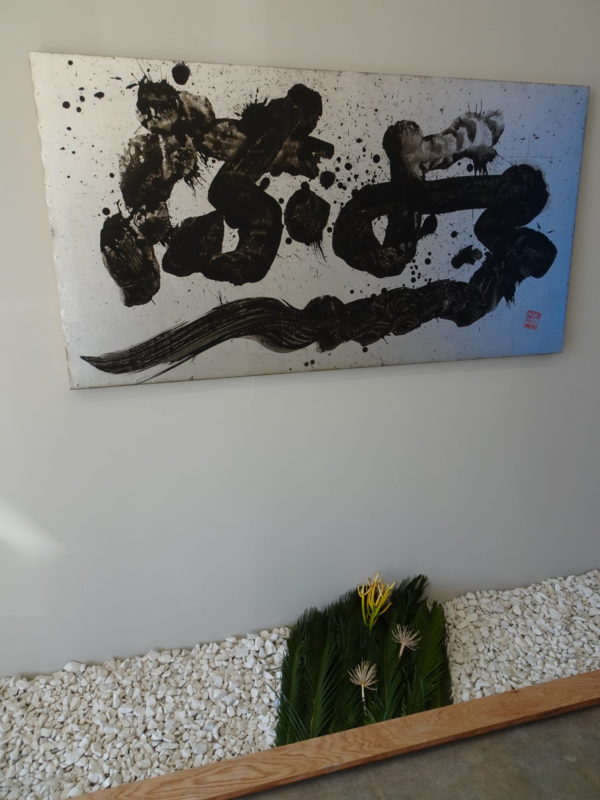

Entering Nonaka-Hill feels like stepping outdoors into a Japanese rock garden. Plant matter and sculptures populate a white-pebble substrate. Evoking sky or water, deep blue walls contribute to a sensation of tranquility. The parking lot outside seems a world away. You could almost imagine yourself undersea, with the lacunate sculptures as coral formations. Their creator, Sofu Teshigahara, (1900-1979) espoused an avant-garde ethos rooted in Japanese tradition. His abstractions reference Shinto legends and symbols of old Japan while exuding modernist principles akin to Western sculptors such as Henry Moore. Tachi (1968), for instance, is titled after a traditional sword worn by samurai—a custom banned in 1876, though the sword endures as an emblem of valor. Teshigahara was born in Osaka near the end of the Meiji Era, a contentious period of extreme change during which Japan struggled to preserve her distinct national identity while rapidly modernizing in response to foreign threats. He trained under his father, an ikebana sensei, and began teaching ikebana at the age of 13. Rebelling against strict conventions, he sought to revolutionize ikebana into a modern art form, and left his father’s school in 1927 to establish Sogetsu School of Ikebana. An arrangement of flowers, wood and sago palm fronds meanders across the floor like an algae-filled stream: this is an ikebana created by Teshighara’s direct pupil, contemporary Sogetsu School sensei Kaz “Yokou” Kitajima. The sprawling ikebana’s sinuosity echoes the movement of Teshigahara’s dazzling 1977 calligraphy piece, Ryusui (“flowing water”), symbolically flowing underneath it as if to betoken an ongoing current of Japanese tradition through Teshigahara’s legacy.

Nonaka-Hill

720 N. Highland Ave.

Los Angeles, CA 90038

Show runs through Mar. 28