Don Bachardy found his lifelong metier at the movies—he was drawn to the larger-than-life faces on the silver screen, especially those of actresses, and began drawing those faces, copying their likenesses from popular movie magazines. Later, when he moved in with Christopher Isherwood—yes, that Christopher Isherwood, the celebrated author of The Berlin Stories—it was the older man who encouraged him to go to art school and explore his talents. “He urged my attention towards becoming an artist,” says Bachardy in an interview at his Santa Monica home, his speech inflected with the formal diction and touch of British accent gleaned from living with Isherwood for over 30 years. (For a look at their extraordinary relationship, see the 2007 documentary, Chris and Don.)

Don Bachardy, Self Portrait 2017, acrylic on paper, 29×23, signed by Don Bachardy

Isherwood had browsed about a dozen of the young man’s works. “He recognized every subject, and he asked, ‘Have you ever worked from life?’” Bachardy continues.“I said ‘no’ and he said, ‘I’ll sit for you.’ That was my first drawing from life. Drawing from photographs is hopeless, but what I had been doing was training my eye.” Bachardy enrolled in the Chouinard Art Institute, which was downtown, and for four years, he religiously drove there Monday through Friday, and honed his skills. He had started with pencil, but learned to use other media and worked with live models.

Don Bachardy, Ellen Burstyn, July2 1987, acrylic on paper, 29×23, signed by Ellen Burstyn and Don Bachardy

Being in Los Angeles and Isherwood’s partner had considerable benefits—the young man often rubbed shoulders with actors and writers and other celebrities, and he asked them to sit for him. Soon he became known as a gifted portrait artist and began getting commissions. His A-list of sitters includes Bette Davis, Ginger Rogers, Fred Astaire, Rita Hayworth, Katharine Hepburn, Gore Vidal, Natalie Wood, George Cukor, and Edith Head—and of course he drew Isherwood over the decades, including a series while he was dying. More recent subjects have included Jerry Brown and Angelina Jolie. Over the years Bachardy has had a number of gallery and museum shows—he shows regularly at Craig Krull Gallery, and last fall he had an exhibition of female subjects, “The Women, 50 Years of Portraits,” at Santa Monica College’s Barrett Art Gallery. Last year he also produced a coffee table book, Don Bachardy: Nudes, the culmination of five months’ work when a patron regularly sent professional male models to him to paint.

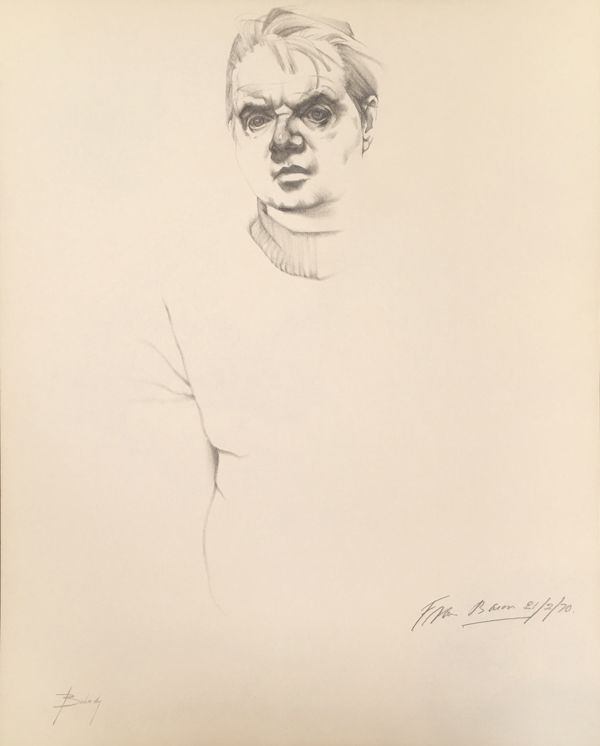

DonBachardy, Francis Bacon, February 21 1970, graphite on paper ,29×23, signed by Francis Bacon and Don Bachardy

“Nowadays I do mostly head and shoulders,” says Bachardy. “I start with the shape of the face, sometimes just a few brushstrokes for the forehead, and immediately start putting the eyes in.” He doesn’t do under-drawings—partly because sitters these days find it hard to sit for long—and uses a brush dipped directly into jars of acrylic paints. “I mix my paint on an enamel tray made for hospitals; chefs use them, too.” He usually opens and sets out jars of nine colors, including magenta, red, orange, yellow, green and two blues. “I could do a palette with five colors,” he says, “even four if I have to.”

Don Bachardy, Peter Alexander August 31 1998, acrylic on paper, 29×23, signed by Peter Alexander and Don Bachardy

Years ago, Bachardy called me up to ask if I would sit for him. We’d met several times, and had acquaintances in common. Sure, I said, and we arranged a day for me to visit him in Santa Monica. The studio is a two-story building renovated from a former garage, and is separate from the house. I had gotten a few pointers from my friend, the late Victoria Blyth Hill, who had sat for him before. He will do one or two quick studies, she told me, then work on a more detailed painting for a couple of hours or so. He won’t talk while working, so I shouldn’t expect to have conversation.

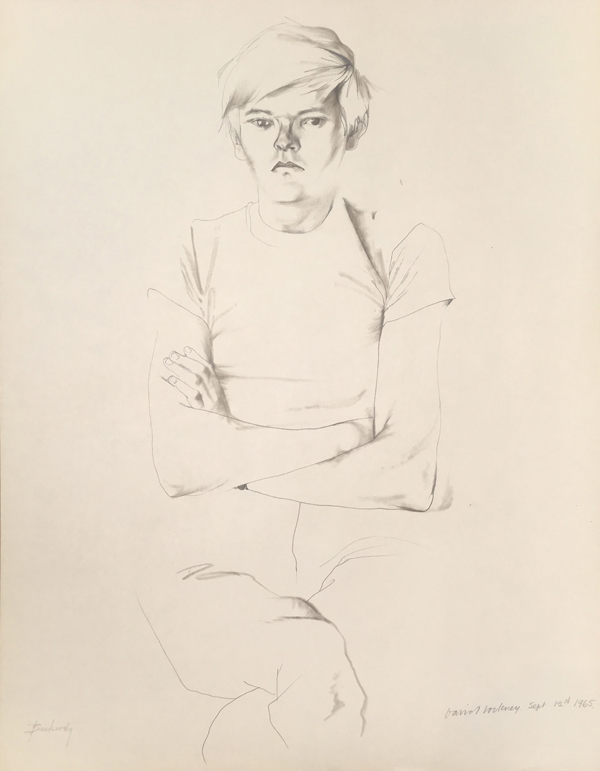

Don Bachardy, David Hockney September 12 1965, graphite on paper, 29×23, signed by David Hockney and Don Bachardy

When I arrived, we quickly went into the studio and climbed to the second floor. I sat in a chair on one side of the room, looking towards a large picture window with a view of the Santa Monica Mountains and the Pacific Ocean beyond. I looked at the houses hidden among the trees, at the trees moving in the sea breeze, and after a while I started to zone out a little. Bachardy was perched with his drawing board a few feet away, and he would look intensely at me, then down at his paper and make some marks, before staring at some part of my face again. The quick drawings were in black and white, the longer one with colored paint. At some point I got a bottle of water. We took a couple of short breaks, and then, about an hour into the longer portrait, he muttered and shook his head. “I can’t get it,” he said, “I just can’t get it right today.” When I went to look at the pictures, I had to agree. The portraits were good, but they were not me. He had the sense to call it a day.

Don Bachardy, Jerry Brown October 8 1983, acrylic on paper ,29×23, signed by Jerry Brown and Don Bachardy

Years later, in a role I’m more familiar with—as an arts journalist—I ask him why, after six decades, the human face still fascinates him.

“What better information can you get from a creature you’ve never met before?” Bachardy says. “I was interested in people and personality. The personality, how is it expressed? Bodily—eyes, nose, mouth, hair and full figure. I was just wildly interested in people.”