COLA 2020

Sadly, so many art events, exhibitions, and performances have had to be canceled during Q time—too many to mention. Here I give a nod to the annual show for the COLA (City of LA) award winners from the previous year. They are each given $10,000 to create new work to be featured at the LA Municipal Art Gallery (LAMAG), in an exhibition that is often an important milestone in the artist’s career. This year they had a virtual exhibition instead, with artists Tanya Aguiñiga, Amir H. Fallah, YoungEun Kim, Elana Mann, Hillary Mushkin, Alison O’Daniel, Vincent Ramos, Shizu Saldamando, Holly Tempo, Jeffrey Vallance and Lisa Diane Wedgeworth. Let’s hope LAMAG will make an effort to feature them in a IRL exhibition next year?

Carmen Argote: “Glove Hand Dog,” 2020, installation, courtesy of the artist and Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles, photo by Ruben Diaz.

Carmen Argote: Through a Pandemic Darkly

On a very hot Saturday afternoon, Carmen Argote greeted me at the entrance to Stairwell gallery—the stairwell and living room of a quadraplex apartment in Pico Union, where she had spent a residency and produced some of her latest, very compelling work. She was her slimmed down self after a serious illness (not COVID) earlier this year, but assured me she had recovered—briefly lifting her mask to show me the radiant smile beneath as we sat, at least 6-feet distant, on the stairs.

The new work is being shown here, as well as at Commonwealth and Council and at Clockshop. At the latter she made her first film, a 12-minute short called Last Light, which is made up of stills, videos and her voiceover ruminations as she walked the desolate city, day after day. (The film was streamed online July 21, as part of a program co-presented by Clockshop and the Hammer, and can be seen at Clockshop by appointment.) The works on paper have a relationship to each other, as well as to the film. They came out of her feelings of fragility and change, out of her long walks, and her thoughts about our collective malaise during this unprecedented time.

Argote emphasized how everything just evolved; she didn’t have an exhibition or a film in mind when she started. The film format “seemed to fit the moment to me, it seemed a way to access the psychological,” she said. She recorded footage on her phone, then a photographer accompanied her on two walks. The eventual voiceover “emerged from the process of walking and thinking.”

On her walk she often passed a dog behind a chain-link fence, barking and going into a tailspin. The dog is included in the film and also became inspiration for one group of paintings, “Dog Spin”—where multiple tracings of her own hand became a barking dog, then a spinning vortex.

The other group of work on paper is based on oil seepage onto paper—some made by pizzas, some by rectangular power bars which she would line up. She would trace the contour of the oil stain they left behind, only to find that it would seep even further after she had made her mark. While the “Dog Spin” paintings have a sense of frenzy threatening to spin off the surface, these have a sense of order since they are presented on a grid, as if a set of hieroglyphs.

“I want to know what the work is going to tell me through the process of making the work,” Argote said. “That’s exciting, that’s what makes it worthwhile for me.”

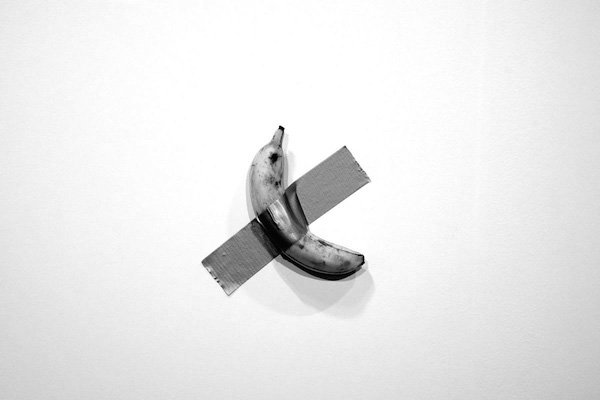

Maurizio Cattelan’s Art Basel Miami Beach’s art piece priced over $100K.

Market Reset

In recent years many of us who focus on the art world have sensed the unnaturally bloated nature of the art market—the astronomical prices living artists were fetching at auction, the proliferation of art fairs, the inordinate attention paid to the frivolous and the frothy (Maurizio Cattelan’s taped-to-the-wall banana at the last Art Basel Miami Beach, for example). In LA we’ve witnessed the frenzied attempt of art fairs to establish ground, in a place notoriously fickle to art fairs. Paris Photo tried for two years, then failed to come back for a third despite its promises. Our own Photo LA took a hiatus before returning to Santa Monica at the Barker Hangar after a time in DTLA. Frieze LA seems to have hit on the right formula, as it proved on its second appearance this year before COVID hit—singular space (Paramount Studios) with custom tent, high-end dealers plus a selection of emerging ones, and curated programming. We even saw Art LA Contemporary reconfigure itself into the Hollywood Athletic Club during what became art fair week—with some success.

Stats confirm the bloatedness and concentration of the business. In the last decade, says the 2020 UBS and Art Basel Global Art Market Report, art sales in the U.S. more than doubled, to $28.3 billion in 2019. Meanwhile at worldwide auctions, 44% of sales proceeds for work by living artists went to 20 artists, that include—surprise!—Jeff Koons, David Hockney, Ed Ruscha and Gerhard Richter.

How will this look after we all start getting inoculated for COVID, which may be early next year? Unfortunately, I think a lot of small to mid-sized galleries will be gone, unable to survive the long closure and collector’s flight, even if they do manage to have limited, by-appointment hours. You’d think rents would become more affordable, but so far I haven’t heard of significant drops in that area, especially since many galleries are on multi-year leases. I have, however, seen a lot of new “for lease” signs in commercial areas.

Luchita Hurado portrait.

R.I.P. Luchita Hurtado

After a lifetime of obscurity, painter Luchita Hurtado became an art star in her 90s Her late career was nothing less than meteoric—featured at the Hammer’s Made in LA in 2018, celebrated with a major retrospective, “Luchita Hurtado: I Live I Die I Will Be Reborn,” at the Serpentine Gallery in London last year. This February that retrospective opened in her hometown of Los Angeles, at LACMA, but closed early due to COVID. In August, at the age of 99, Hurtado passed away of natural causes, as announced by her gallery, Hauser & Wirth.

Born in Venezuela, Hurtado moved to New York at age 8 with her family. As an adult she worked as a fashion illustrator and designer, and in the mid-’40s moved to Mexico City with her second husband, the Austrian Surrealist painter Wolfgang Paalen. There she fell in with an art crowd that included Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera and other Mexican muralists. But the marriage fell apart, and Hurtado moved back to the U.S., and to California. Eventually, she married the artist Lee Mullican.

Hurtado continued to make her own artwork throughout—it was a necessity to her, as she has said. Among her best known are paintings that combine a woman’s body with tribal or indigenous motifs or the landscape. She wasn’t bitter about being neglected for so long. As she said in Ursula magazine last year, “I don’t feel anger, I really don’t. I feel, you know: ‘How stupid of them.’ Maybe the people who were looking at what I was doing had no eye for the future and, therefore, no eye for the present.”

Hopefully, when LACMA reopens, the show will still be there.