Comings and Goings

We say farewell to Marc Foxx Gallery on Wilshire Boulevard, in business since 1994. Interestingly, they’re not a victim of the disruptive Metro construction on Wilshire; their building wasn’t effected, but one of the partners, Rodney Nonaka-Hill, has long wanted to open his own gallery and reportedly will in March. Meanwhile, Marc Foxx Gallery is in the process of shipping art back to artists, and aiming to close by the end of February.

Bergamot Station as we knew it…

And farewell to Bergamot Station—but wait, not really! In early January, Shoshana Wayne Gallery sent around a press release saying, “After a remarkable 24 years, the Bergamot Station ltd. Arts Center in Santa Monica is closing. Shoshana Wayne Gallery will relocate and reopen with an exciting new exhibition program.” Shortly after, other communiqué told us that Bergamot lives on! Turns out Shoshana and Wayne Blank are pulling out their gallery from the popular Santa Monica arts complex, and taking with them its incorporated name. However, some 20 galleries—including stalwarts Robert Berman, Craig Krull, Skidmore Contemporary Art and William Turner—are staying in what is now being called “Bergamot.” (Hmmm, let’s hope they come up with a more self-explanatory name in the near future.)

Their new landlord is the Worthe Real Estate Group, which won the bid to revitalize the parcel for the city of Santa Monica in 2014. That parcel consists of five acres on municipal land, with 25 tenants including City Garage Theater, a café, a florist and galleries. It’s ironic that the Metro, which was supposed to have been a boon to the arts complex, has had the effect of tearing it apart—with multiple groups vying for its redevelopment now that the parcel has become so valuable. At least Worthe is planning “much-needed upgrades to the site” which will be most welcome, as things have been looking a tad shabby for some time. As of January 1, 2018, the property was renamed “26th Street Art Center.”

“There are a lot of development issues we will continue to debate and discuss,” says Turner. “The Worthe team has been given a three-year interim master lease, the galleries have been given a one-year interim lease. We’re trusting that we’ll have longer leases in the future. Bergamot is a cultural center on the west side like no other. My message to the City Council has been that it’s a fragile ecosystem that’s evolved in an unlikely place, and it’s been a tremendous success. It needs to be developed cautiously and with care if it is to survive and thrive.” Yes, there have been increases in rent—which have always been below-market—but fortunately, says Turner, the increases were based on the Consumer Price Index, and not market value.

A real farewell to PST LA/LA, which in January wound down to a close with a series of performances. Yours Truly caught “Variedades” (Jan. 18), curated by Marcus Kuiland-Nazario and based loosely on old-time vaudeville shows. Energetically hosted by Rubén Martínez and Raquel Gutiérrez, the show took place at the eye-popping Mayan Theater downtown with its main and two side stages. It offered a diverse set of talents—from voguing drag act, to performance pieces (Nao Bustamante’s piece about a young girl trying to escape a stalker was both harrowing and hilarious), to song and dance. A showstopper was the performance of Alice Bag, who has had a long history in LA music—she was the lead singer and co-founder of one of the first punk rock groups in LA in the 1970s, The Bags. At “Variedades” her heartful duet with Dorian Wood on her song, “Inesperando Adios,” was so very very moving—and timely, too, since it’s about a loved one suddenly disappearing, probably picked up by ICE. “You didn’t say goodbye, they didn’t give you time,” go the lyrics. “You were blown away like a leaf in the wind.”

LA Art Show 2018

Art Fair Wrap-Up

The L.A. Art Show (Jan. 10–14) came back to the Convention Center for its 2018 edition. Most of LA’s larger galleries such as Louis Stern and Jack Rutberg have pulled out, but there was a lively complement of Asian galleries—mostly from China, Korea and Japan—and in Littletopia, the section given to Outsider/Lowbrow art. This year Littletopia launched a special salute to Margaret Keane, the real artist behind those big-eyed kid paintings that were so hot in the ’50s and ’60s. (Tim Burton celebrated her life story in the 2014 film Big Eyes, with Keane played by Amy Adams, and her scumbag husband who took credit for her work by Christoph Waltz.) There were some dozen-plus paintings of hers in a mini-exhibition, plus works being sold by her dealer Keane Eyes Gallery of San Francisco. Clearly, Keane is an adept painter, and the assembly of big-eyed animals in Animal Kingdom (1984) was especially charming—though, yes, they can seem like illustrations for a children’s book.

Other booths of note—the Tolman Collection of Tokyo (New York) continues to show exquisite contemporary prints, Jane Kahan (New York) brought quality works by modern masters, and John Natsoulas (Davis, CA) brought some gems in small paintings and sculpture.

On the other side of town at the Barker Hangar, Art L.A. Contemporary (Jan. 25–28) offered a more compact and focused art fair. Overall, it felt like one of the stronger editions in terms of quality of art on offer. Yours Truly especially loved the Analia Saban canvasses interwoven with strips of dried paint at Praz-Delavallade and two works by Carmen Argote at Instituto de Vision (Bogota, Colombia). Argote continues to surprise and delight with her conceptual work, such as Staircase Dress, a custom-made dress covering a stairstep platform topped with a series of coffee makers. It makes a poignant statement about women and domestic labor.

Lee Bontecou

2018 WCA Awards

In 1972 the Women’s Caucus for Art (WCA) grew out of the College Art Association (CAA), amidst the rise of Second Wave Feminism—and the recognition that in art, as in too many other professions, women were underrepresented and under-recognized. Recently the WCA announced the recipients for the 2018 WCA Lifetime Achievement—Lee Bontecou, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Gloria Orenstein and Renée Stout. The award ceremony takes place on Feb. 24 in Los Angeles, this year’s venue for the annual CAA meeting. A big CONGRATS to the well-deserved recipients!

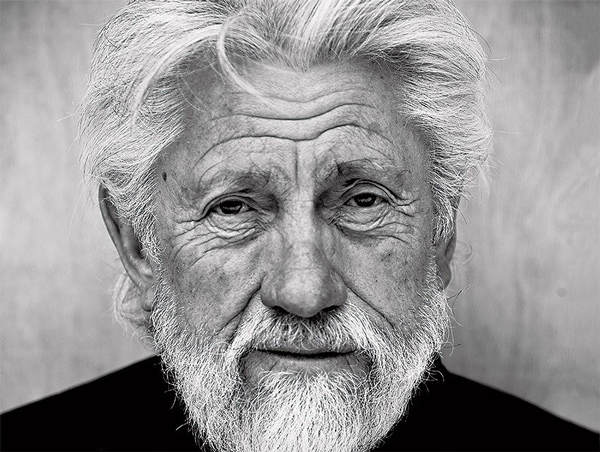

Ed Moses, photo by Kwaku Alston

Ed Moses in Memoriam (1926–2018)

By Frances Colpitt

Ed Moses, one of the most widely known and admired artists in Southern California, died on January 17, at the age of 91. He was primarily an abstract painter although there were periods, both early on and in the ’90s, when he used recognizable imagery to great, never arbitrary, effect. He embraced the modernist dialectic of grid and gesture, sometimes alternately but often synthesized in a single painting, saluting his roots in abstract expressionism and his admiration for Mondrian, Van Doesberg and the Bauhaus.

In the world, Moses’ life careened from adventure to adventure; in the studio, from experiment to experiment, never settling on a signature style in 60 years. He was primarily engaged in process and improvisation, using unpredictable tools: mops, squeegees, garden hoses, snap-lines, squeeze bottles, stencils, finger-painting, even fist and elbow, and déclassé materials: glitter, iridescence, metallic paint, dayglow, resin, crayon, chalk and asphaltum. Recently confined to a wheelchair, he painted right up to the end, relying on studio assistants who had been part of his painting practice for years.

Moses was born in 1926, on a steamer crossing the Pacific from Hawaii to the mainland. Growing up in Long Beach, where his birth was registered, he was a pugnacious boy in spite of his relatively small stature. As an adult, his feistiness, outsized personality and muscular style of painting left the impression of a towering figure with a striking presence, although he was around 5-foot-9” in later years.

Enlisting in the Navy at 17, Moses served as a surgical technician in the Pacific. His experience of war’s horrors was crucial to the expressive power of his paintings, according to Walter Hopps. “The visceral bloodiness of what it was and what it looked like—it was the informing experience of Ed’s life …There is no wonderful Moses without blood, excrement, mucous membranes and all of his delights and terrors.” As cofounder of Ferus gallery, Hopps included Moses in the 1957 debut exhibition. Moses’ solo show the following year served as his thesis exhibition for his Master’s degree from UCLA. Throughout his career, Moses was associated with the gallery, which closed in 1966, although Phil Leider’s sobriquet, “The Cool School,” was ill-suited to Moses’ rarely hard-edge and always “hot” paintings.

During and after college, Moses held a string of enterprising jobs. He was a lifeguard at the Flamingo Hotel in Las Vegas and a sailor on a Portuguese fishing boat. As a bicycle messenger on the 20th Century Fox lot in the early ’50s, he met and had a brief affair with an aspiring Marilyn Monroe. Attracted to her generous behind, he was soon informed that a poor artist wasn’t part of her future plans.

Moses married Avilda Peters in 1959. Their son Cedd was born in 1960 and Andy in 1962. Peters and Moses divorced in 1975, but remained close for many years. After they remarried in 2015, Moses delighted in the reunited family’s nightly dinners at their Venice compound, where Ed, Andy, and his wife Kelly Berg live and work.

Introduced to Buddhism by Ad Reinhardt in New York, Moses converted to Tibetan Buddhism in 1971. While his devotion to Buddhism was lifelong, he was also inspired by prehistoric cave painters. In an unpublished 2011 interview with his physician, Thomas Ahn, Moses explained, “What made it necessary for them to stain and color walls? I think these marks were in response to the thought, ‘I exist.’ …Kilroy was here.” For Moses, painting was by definition mark-making, a belief borne out in his work from start to finish.

Each series of Moses’ work is distinguished by a particular type of mark, process, or palette, absent rational transition or notable progress from one series to the next. Within a series, he discovered a formal or emotional effect that led to the next body of work. Among his most remarkable contributions are his “Rose Drawings” (1963), shimmering graphite fields flecked with tiny roses, and the “Resin Paintings” (begun in 1969), unstretched canvases with diagonal grids of chalk or masking tape and coated with resin. Always interested in architecture and installation, Moses created a groundbreaking “light and space” environment at Riko Mizuno’s gallery in 1969-70. He removed the ceiling and roof, leaving the joists in place, so the gallery’s interior revealed a shifting, diagonally striped pattern of sunlight and shadow. Moses also designed the main building for Chappellet Winery, a huge pyramid of Corten steel with elongated windows, called by The New York Times in 1971, “the most beautiful structure in the Napa Valley.”

By the 1990s, the red or black diagonal grid—interspersed with splashes, pours and stains of brilliant colors—which structured his work in the 1970s and ’80s, dissolved into sinuous “worms” in oily hues on raw canvas. In the last two decades, his spontaneous technique loosened great swaths of brilliant color on massive canvases, testaments to his inexhaustible well of ingenuity and impetuous invention.

Blake, circa 1976, with camera and Portapak, photo by Victor Hugo Zayas.

Rabyn Blake, Artist and Activist (1933–2018)

Notable for her pioneering video pieces shown in the ’70s and collected by the Long Beach Museum and the Getty, Blake also worked in painting, sculpture and mixed-media. Her mudpool happenings and the works arising from them were featured in WET magazine and Artweek and elsewhere. She managed to explore nightmarish matter of death and motherhood with sly humor and beautiful imagery in various media. She also incorporated her art into anti-war, and environmental activism, painting her VW van like a watermelon “bomb” for Greenpeace, turning warships into floating melons and giving warmongers vegetables and flowers to hold on front pages of Cold War era newspapers. In recent years she returned to classical themes and archetypes in her exquisite small sculpture assemblages. She was deeply rooted in the Topanga Canyon community, a member of the great generation of LA beats and hippies, an articulate and fierce, fun-loving and well-loved figure, promoter of poetry and exemplar of a life brilliantly lived.

—Nadia Lili