Attending a Daniel Rolnik event, you’ll encounter many bizarre characters, Rolnik being the most amusing. I met Rolnik four years ago at a party in a vacant Beverly Hills house where he had helped organize a pop-up exhibition. His art world debut role was as a writer where he had developed a reputation as the self-styled “LA’s Most Adorable Art Critic.” Only Rolnik, a master of hyperbole who peppers his diction with superlatives and distends emails with effusions of all-caps words and exclamation points, could assume such a moniker without seeming completely obnoxious.

Rolnik with art in his gallery

A winsome Rolnik with a hirsute face and exuberant demeanor appears much younger than his 27 years. He moves about with an air of easy improbability, like an actor who never breaks character always playing himself. Yet for all his ebullience, he’s a man of contradictions. He resides in Beverly Hills but sells paintings for pittances and provides friends with freeloading tips. Conversing with him, a stranger might not believe that someone so apparently mannerly would invite an obese exhibitionist to appear nude at his gallery openings.

Late in the morning last summer, sitting opposite Rolnik at his small desk in a modestly-sized space he is temporarily subleasing from Flower Pepper Gallery in Pasadena, I am uneasy about interviewing this seasoned interviewer, skilled at flippantly oblique repartee. This is his final brick-and-mortar show. Rolnik’s nook screams in dissonance with the larger gallery engulfing it. Flower Pepper’s walls are white and neat; Rolnik’s are dotted with a salon-style hodgepodge. A big bowl of lollipops interspersed with 3D glasses sits to my right; to my left is Rolnik’s closed laptop plastered with decals. Behind Rolnik, a baseball cap emblazoned with his favorite catchword, “EPIC,” sits jauntily amid haphazard piles of papers atop a printer. Instead of a gallery, I feel like I’m in a cross between an artist’s studio and a teenager’s clubhouse.

Epic ballcap

Rolnik’s mother, Trudy Green, owns Trudy Green Management; his father, James Rolnik, has a degree in sculpture but according to Daniel, now sells toilet paper door-to-door in Las Vegas. Rolnik found art boring until he was about 12 when his father took him to a show at La Luz de Jesus that caused him to reevaluate his prejudice.

His budding fascination for lowbrow art was secondary to his music obsession. In high school, he played in a rock band and wrote for the fledgling LA Record.

Studying Audio Engineering at the Ex’pression College in Emeryville, Rolnik started an art and music magazine that helped land him a post-graduation job as publicity agency art blogger in 2011.

Returning to LA, he wrote about exhibitions nearly every day for the agency and other outlets. He developed his outlandish persona and soon began curating shows for artists and gallerists about whom he had written.

In 2014, Om Bleicher, owner of bG Gallery, asked Rolnik if he knew anyone who might want to take over an oceanfront sublease. Overnight, Rolnik decided to open a gallery himself.

“It started out as a white-walled traditional space, but then it was like a sickness to me,” Rolnik says. To make himself feel at home, he painted the walls different colors; this inspired even more eccentric arrangements.

Visiting Rolnik’s Santa Monica gallery for the first time, I was astonished by his casual display. The gallery was a mess; art and T-shirts and all sorts of other items covered floors and walls; but the utter chaos was weirdly engaging, accompanied by Rolnik’s cheerful show-and-tell banter. As he nonchalantly picked up miscellaneous pieces and explained their back stories, I was overwhelmed by the feeling that the gallery doubled as Rolnik’s own studio in which others’ art served as raw material for his own installation and performance.

Over a year later, in a different location, I still feel like I’m in his studio.

“You are,” he affirms. “When I started the gallery, I wanted it to be my art project, too.” When asked if he views himself as a performance artist, he replies, “I view my life as kind of a weird work of art.” The Living Theatre is inspirational, and his greatest influence is Allan Kaprow’s Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life (1993).

“It’s an idea that you’re almost supposed to forget and just exist as,” he says of Kaprow’s ideology, which he applies to own “weird place where I’m an artist and not an artist at the same time.”

He aspires “to be this unique, weird, creature with stories that’s this aggregator of culture,” he says, laughing. “The gallery is the white-walled space that’s supposed to showcase the artists, and when the artist isn’t there, it’s in a white, blank canvas state. That’s the traditional gallery. So for me, it’s just the opposite. I am just as much of a part of the gallery as the artist. Me interacting with the people that come in is just as much of the art as the art on the wall.”

Rolnik’s gallery seems like a burlesque of traditional galleries; however, he appears to believe in the artwork he shows. His enterprise is a substantial investment of resources. “At the end of the day, I’m still an artist who happens to be in a commercial endeavor to try to make artwork as a living.”

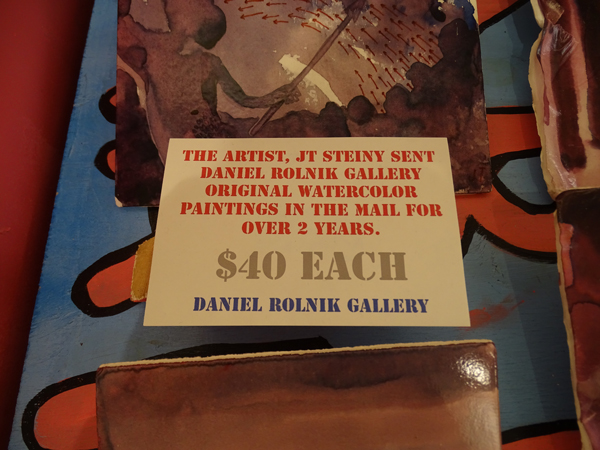

Cheap art…

Yet few of his pieces are priced at more than a few hundred dollars; most are less than $100. Why doesn’t he sell higher-end art? He explains that as a curator without control over prices, he was dismayed by work going unsold. As a dealer, he values quantity over quality: rather than waiting for expensive works to sell, he wants to move as many pieces as possible.

As opposed to moneyed collectors, his target is what he calls the “new market of the fan:” art enthusiasts who follow artists and purchase directly from their websites and social media. As a dealer, Rolnik seeks to tap that market by creating—through social media and live events—his own society whose followers can interact with him and his artists. “There’re so many people in this world who hate art because they think it’s boring, like I did when I was a kid. I thought maybe if I made it affordable and accessible and fun, that more people would get into it and bring it back home. For me, art is more about taking it home than seeing it up on a wall and leaving.”

As Camus discussed in his writings, there is something inherently absurd about creating art. “I’ve always tried to bring humor through art, and that’s another reason I’ve never had an expensive price point,” Rolnik notes. “When you take something that’s funny and put a million dollar price point on it, it’s kind of not funny anymore. It’s a serious decision to buy that piece.”

Epic ballcap

Rolnik is a jester who laughs at himself as much as anyone else does. However, not everyone finds him funny. His misadventures could easily fill a tome. In less than two years, his gallery inhabited three spaces. In June, just three months after moving from Santa Monica, he vacated his Culver City location after his landlord shut down a boisterous carnival-esque art fair he was hosting outside. “I don’t like rules and being told what to do, so inevitably I find myself getting into trouble with people who love rules and their version of rules,” Rolnik states with a rare hint of overt cynicism. “I’m not going to cower from them, so it ends up being a fight.”

About a month after moving into Flower Pepper, his attempt to start an art walk resulted in lawsuit threats from a local businesswoman and cease-and-desist letters from the City of Pasadena. “I think I get in trouble, too, because I don’t ask permission, I just do things because I have the idea and I want to do it,” he reflects. It seems that his idealism often causes him to underestimate potential negative consequences of his actions. But negative consequences run off him like water off a duck’s back; he wears his problems proudly.

He’s tired of operating within gallery confines. “My idea now is we’re not just a gallery, we’re almost a cause,” he declares of his new pop-up format. Starting in September, he began hosting shows in bizarre locations, the first of them a cave. The “constant collaboration” between him, artists and fans is more extreme in this new iteration he calls “Phase II” of his gallery. “It’s the ultimate way for me to be a rebellious person, too,” he says, giggling. “To rebel even against what the gallery is.”

See Daniel Rolnik’s pop-up gallery installation, “Turtle Wayne’s House at Daniel Rolnik Gallery,” in Booth # 1129 at DesignerCon in Pasadena this weekend, November 19-20.

0 Comments