I’m thinking about family albums right now – not something that comes to mind very often (and now I’m wondering if this is the first time I’ve ever considered this). I suppose this could also be something captured and stored digitally – but for some reason, it doesn’t seem like quite the same thing. It’s the sort of thing that almost demands to be manually flipped through with some parent or aunt or uncle or older (or I suppose younger) sibling – preferably with large cocktails in hand. (That would be the ‘mandatory minimum’ in my not-especially-sentimental DNA pool.) I can’t recall ever seeing more than one of these items at my parents’ house. Nor can I recall an instance of anyone spending any length of time poring over one.

I realize it’s not quite the same thing, but I think this is one reason why journalists are fond of end-of-year wrap-ups and compendiums of highlights or critics’ picks. As readers of this blog will know, ARTILLERY has itself not been averse to this popular tendency in recent years. My own practice is a bit more random – in part because I’m always out there looking, listening, picking up stories – even if I’m not always reporting or writing about them. My own ‘albums’, aside from the notebooks and chunks of legal pads I hang onto, tend to veer away from the stories, subjects or artists I’m following. Instead, they’re mostly looseleaf binders of clips and photos torn from newspapers and magazines – usually concerning stories or subjects that have a power or personal significance well beyond the scope of what I’m doing or who I’m following in Los Angeles or anywhere else in the world. I guess you’d have to call these my ‘family albums’.

Getting back to those albums, compendiums and year-end lists more familiar in magazines and newspapers – one of the frustrations in compiling them is the realization that for all the legwork you’ve done, you actually haven’t seen or heard everything you would have considered (then or now) a must. There was at least one instance of this I was aware of as of last week; and to my shock and horror there is another this week. Fortunately, it’s not too late for the rest of you to go see this show, either – and I would encourage you to do so immediately – in any case no later than Saturday afternoon.

Do you remember Hecate – the Greek goddess of sorcery? I didn’t recall much about her mythology, but hers has an especially interesting twist in that some of her divinity and oracular power survived the cross-over into the early/post-Christian domain. Whatever the local religious trepidations, Hecate was seen as a protective household goddess who warded off the dark and restless spirits of the underworld. This was carried forward to some extent through the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance and Reformation. (Consider, e.g., that the witches of Shakespeare’s MacBeth are actually scolded by Hecate’s spirit and given some ground rules for their meeting with that ill-fated Thane.)

Curator Sara Hantman has embraced that spirit as well as its more contemporary second wave feminist inspirations – specifically, W.I.T.C.H., an offshoot of New York Radical Women, founded by, among others, Robin Morgan, which became a collective of political activists, media artists and others (including men), which in many ways was a precursor to later activist movements, including ACT-UP, Code Pink, and the current re-energized third- (or is it fifth?) wave women’s movement. I love that W.I.T.C.H. originally stood for “Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell.” The name (which was actually shared by several organizations under a common umbrella) was later expanded to somewhat less aggressive and more inclusive versions; but at their peak, they did not shy from shock tactics. Their collective eyes were always ‘on the prize’ of taking down the patriarchy on every level.

Hantman’s show ranges across generations (going directly back to that W.I.T.C.H. generation) and, not unlike WITCH itself, across genders. You’re charmed ‘firm and good’ just walking into the gallery (leaving a ‘burning bridge’ behind, courtesy Pete Drungle’s and Marianne Vitale’s audio installation), passing directly by a ‘witches circle’ of what might be silhouetted peaked sorcerer’s hats or miniature ghost ships with their dark spiritual cargo (Jupiter, 2013 – also by Vitale). Resist the urge at the front desk to caress what looks as much like a Turkish or Bulgarian dancing slipper as something a witch might wear – this one executed in sensuous green marble, the work of Nicky Lesser (Stuck In A Curly Point, 2017).

Anna Sew Hoy’s 2007 Circuit functions as a kind of vortex amid the coven of occult, incantatory expression on the walls. Here it takes on a kind of gravitational, subterranean energy and power – a kind of witches circle or devils dance assembled out materials which themselves represent a dark convergence of human flesh (or its absence) with the arboreal (or its negation. Black charred-looking tree limbs emerge from long black denim jean peg-legs – prostheses from hell – which themselves connect with more denim and coiled T-shirt material spiraling in and out sections of blackened tree trunks, the whole of which snakes through and around or away from an off-center black mass like some post-organic os or spent aorta – expired, yet seeming to press its morbid flow.

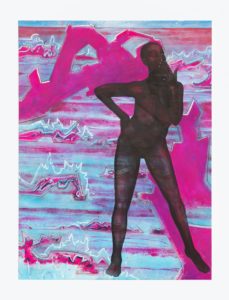

Cy Gavin’s works here, which cast a fevered spell, are parenthetically subtitled “Sally Bassett” – tributes to a woman held under (and eventually dying under) medieval conditions as a slave in early 18th century Bermuda. Under slender evidence, Bassett was charged with attempting to poison a (white) couple and one of their slaves and sentenced to burn at the stake. She went to her fate defiant to the end on the summer solstice of June 21, 1730, and the local legend was that amid the ashes she left behind bloomed a purple iris later named the Bermudiana. The execution fueled the legend of her witchcraft and was said to have triggered several slave rebellions. In Gavin’s 2017 Woman, Yawning, a beautiful nude stands securely, confidently (and slightly transparently – she is a ghost after all) on an invisible shore, one hand raised to her mouth, the other placed casually on her hip, as striated waves in ice-blue and hot fuschia churn into electric goblins dancing on the surface – as if hurricane torn tree limbs being carried out to see. Gavin pays further tribute to the legend with a black wax head that is actually the product of several molded and sculpted Palo Mayombe candles – scented with essences of that same ‘Bermudiana’ iris.

Cy Gavin’s works here, which cast a fevered spell, are parenthetically subtitled “Sally Bassett” – tributes to a woman held under (and eventually dying under) medieval conditions as a slave in early 18th century Bermuda. Under slender evidence, Bassett was charged with attempting to poison a (white) couple and one of their slaves and sentenced to burn at the stake. She went to her fate defiant to the end on the summer solstice of June 21, 1730, and the local legend was that amid the ashes she left behind bloomed a purple iris later named the Bermudiana. The execution fueled the legend of her witchcraft and was said to have triggered several slave rebellions. In Gavin’s 2017 Woman, Yawning, a beautiful nude stands securely, confidently (and slightly transparently – she is a ghost after all) on an invisible shore, one hand raised to her mouth, the other placed casually on her hip, as striated waves in ice-blue and hot fuschia churn into electric goblins dancing on the surface – as if hurricane torn tree limbs being carried out to see. Gavin pays further tribute to the legend with a black wax head that is actually the product of several molded and sculpted Palo Mayombe candles – scented with essences of that same ‘Bermudiana’ iris.

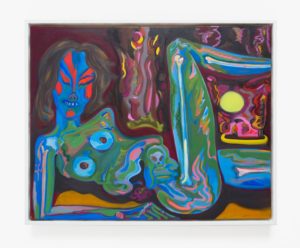

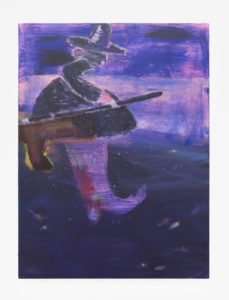

If there were such a thing as magical Expresionism (which I guess by now there might as well be), Rainen Knecht might easily be credited as one of its creators. That’s not exactly the case since there are instances of this style in the echt Expressionism that came to full flower in Weimar Germany. But some of these canvases are like spells – Expressionist voodoo images. Her Ants (2017) reverts to a kind of classic Expressionism – the Expressionism of Kirchner and Schmidt-Rotluff – except that this is clearly a zig-zag dance of desire. The other two canvas-spells are hers alone, though – the color laid down like stained glass. Directly across from these incantations, Katherine Bradford’s Broom Saddle (2017) sweeps through an almost Rothko-esque atmosphere if amethyst and indigo, a pale, luminous cowboy boot descending ahead into the blue depths, clearly ready to kick some ass. She’s flanked by Julie Curtiss’s play on a a kind of fetish-spell (Honey Moon) and, conceivably, its aftermath (Second Thought) – both 2017.

If there were such a thing as magical Expresionism (which I guess by now there might as well be), Rainen Knecht might easily be credited as one of its creators. That’s not exactly the case since there are instances of this style in the echt Expressionism that came to full flower in Weimar Germany. But some of these canvases are like spells – Expressionist voodoo images. Her Ants (2017) reverts to a kind of classic Expressionism – the Expressionism of Kirchner and Schmidt-Rotluff – except that this is clearly a zig-zag dance of desire. The other two canvas-spells are hers alone, though – the color laid down like stained glass. Directly across from these incantations, Katherine Bradford’s Broom Saddle (2017) sweeps through an almost Rothko-esque atmosphere if amethyst and indigo, a pale, luminous cowboy boot descending ahead into the blue depths, clearly ready to kick some ass. She’s flanked by Julie Curtiss’s play on a a kind of fetish-spell (Honey Moon) and, conceivably, its aftermath (Second Thought) – both 2017.

There are two galleries of work here, and in both, the east walls are occupied by tapestries. I use the term loosely, but Sanam Khatibi’s The hollow in the ferns (2016) is literally a wool tapestry – hand-woven – and it’s a masterpiece. Khatibi’s is almost bucolic by comparison with the abstracted surreal terror of Anna Glantz’s Traveling Horse (2017), but they both make beautiful focal points in their respective spaces.

The links and resonance among each of the works is part of what makes this show so extraordinary. Khatibi’s magical, erotic works (there are two others – including one I would like for Noel/Hannukah – hint, hint….) bear uncanny affinities with the quasi-domesticated (I almost wrote somnambulant – seriously) surrealism of Jessie Homer French (a senior Witches of Eastwick here).

But in the meantime – the spirit of all these conjoined spells is present in the flesh – in the photographic sense. Hantman has managed to include three color photographs of Ana Mendieta’s Untitled (Glass on Body Imprints) (1972), a performance memorialized and excerpted here. It’s a haunting in three brief reveals.

Walter Price’s Ma’at cha (2017) sub-aquatic spell is also in the second gallery – and my personal prayer is that it radiates healing energy to our threatened coral. Nor, while I’m in a prayerful attitude should I ignore Altar in the center of this gallery – as well as two actual Hexes in the first gallery by Lazaros – a local practitioner of dark (as well as fine) arts. (Is there a difference really?)

As we’re accustomed to celebrations of light in the darkest days of the year – and even the darkness of our auto-destructive civilization is eclipsed by the darkest days our planet has known since the demise of the dinosaurs – I’m hard pressed to think of a better place to usher in the solstice than this show of dark-bright lights.